The 2026 Winter Olympics in Milan-Cortina were staged against a backdrop that is becoming impossible to ignore: warming winters, shrinking snow reliability and growing scrutiny of the carbon footprint tied to the Games themselves.

An Olympic Games Shaped by Climate Volatility

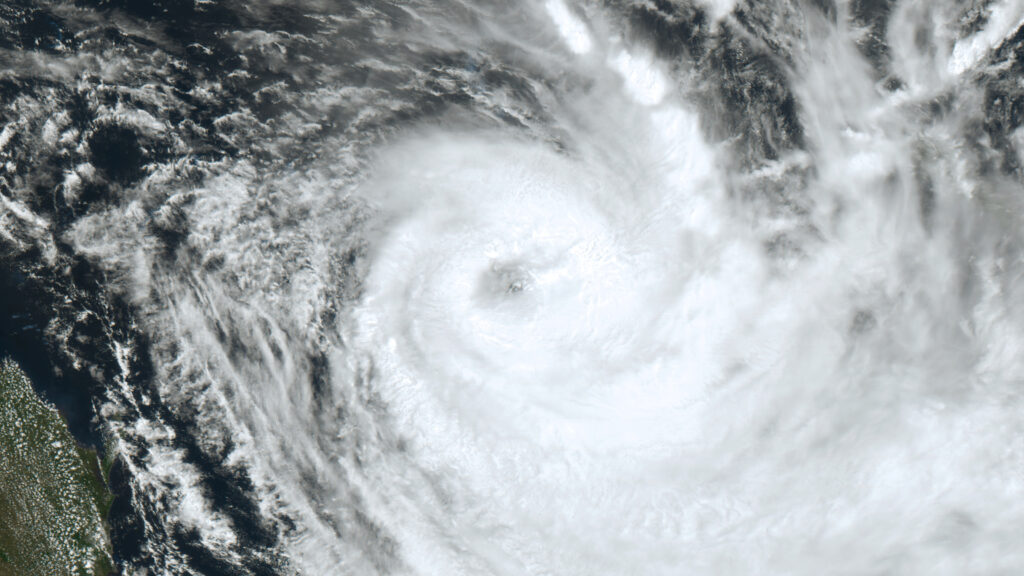

Just days before competition began, heavy snowfall forced the cancellation of the first women’s downhill training run. On the surface, it seemed like a classic winter disruption. But scientists point to a more complex pattern.

As climatologist Davide Faranda explained ahead of the Games, climate change is warming winter temperatures overall, reducing the number of freezing days, while at the same time increasing the atmosphere’s moisture-holding capacity. When cold spells do occur, they can bring intense snowfall events. The result is a paradox: fewer stable cold periods, punctuated by heavier and less predictable snowstorms.

Erratic weather is no longer an anomaly. It is becoming a defining feature of modern winter.

Warming Trends Since 1956

The longer-term data around Cortina is striking. Since it last hosted the Winter Olympics in 1956, February temperatures have risen by 3.6°C, resulting in 41 fewer days of freezing conditions each year.

Climate Central analysis shows that many former and potential Olympic host cities are experiencing similar declines in cold reliability. Under current warming trajectories, only about half of today’s Winter Olympic host locations are expected to remain climatically viable by the 2050s.

This has major implications for the future of the Games. Artificial snow production is becoming increasingly central to staging winter sport at scale. While often framed as a practical adaptation, it requires significant water, energy, and infrastructure — and underscores how narrow the climatic margins have become.

The Carbon Footprint of the Milano-Cortina 2026 Winter Olympics

The 2026 Winter Olympics are not only affected by climate change — it also contributes to it.

The Games’ core activities are estimated to generate roughly 930,000 tonnes of CO₂ equivalent, with spectator travel alone accounting for around 410,000 tonnes. When emissions “induced” by major high-carbon sponsors — including fossil fuel company Eni, carmaker Stellantis and airline ITA Airways — are factored in, the total rises by an additional 1.3 million tonnes.

Those emissions are projected to contribute to the future loss of millions of tonnes of glacier ice and several square km of snow cover — the very foundation winter sport depends upon.

The tension is evident: an event built on snow and ice remains closely linked to the fossil fuel economy driving its decline.

Sponsorship and Growing Scrutiny

In the lead-up to the Games, fossil fuel sponsorship became a flashpoint.

Greenpeace Italy released a satirical video highlighting oil and gas company Eni’s role as a premium sponsor of the Milan-Cortina Games. The campaign calls on the International Olympic Committee to end fossil fuel sponsorship of the Olympic and Paralympic Games.

Campaigners draw parallels with the IOC’s decision at the 1988 Calgary Games to take a stand against tobacco advertising — a move widely credited with helping remove tobacco’s influence from elite sport.

Public sentiment appears to be shifting. Recent polling across winter sports nations suggests that roughly eight in 10 respondents support ending fossil fuel advertising and sponsorship in winter sports.

For the Olympic movement, the issue extends beyond branding. It raises questions about alignment between scientific consensus, public expectations and commercial partnerships.

A Narrowing Future for Winter Sport

Researchers warn that without rapid emissions reductions, the geographic viability of future Winter Olympic Games could shrink considerably. Warmer baseline temperatures mean greater dependence on artificial snow, shorter natural seasons and increasing financial and environmental costs.

Mountain economies — from ski tourism to local hospitality — are already feeling the pressure of shorter, less predictable winters.

As Stefan Uhlenbrook of the World Meteorological Organization has noted, reduced snow-cover days at lower altitudes are making winter snow sport increasingly uncertain. The implications extend far beyond elite competition.

The 2026 Winter Olympics as a Look Into the State of the Climate

The Winter Olympics 2026 offered moments of extraordinary athletic performance. But it also served as a visible reminder of the climate realities reshaping winter itself.

It highlighted three overlapping dynamics.

- Climate impacts: Rising temperatures and declining freezing days are reshaping winter conditions.

- Adaptation pressures: Artificial snow and climate resilience measures are becoming indispensable.

- Structural contradictions: Emissions from travel and high-carbon sponsorship remain intertwined with the event’s footprint.

The Olympics have historically shaped social norms — from anti-doping reforms to the removal of tobacco advertising. As the climate crisis accelerates, winter sport stands at a crossroads.

The spectacle of snow and ice remains powerful — whether it can remain sustainable in a warming world is the more pressing question.

Sara Siddeeq

Sara Siddeeq is a climate and energy writer with bylines in New Energy World, Climate News Australia, and Batteries and Energy Storage Technology (BEST) Magazine. She specialises in covering clean energy, carbon markets, and climate resilience, bringing clarity to complex topics. Sara holds a qualification in Communicating Climate Change for Effective Climate Action and is passionate about data-driven climate storytelling.

Sara Siddeeq is a climate and energy writer with bylines in New Energy World, Climate News Australia, and Batteries and Energy Storage Technology (BEST) Magazine. She specialises in covering clean energy, carbon markets, and climate resilience, bringing clarity to complex topics. Sara holds a qualification in Communicating Climate Change for Effective Climate Action and is passionate about data-driven climate storytelling.

![Asia’s Water Crisis: Floods, Storms and Rising Seas [Part One]](https://www.climateimpactstracker.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/shutterstock_2020796807-1-1024x576.jpg)