Typhoon Wipha roared into the South China Sea in late July with enough punch to force Hong Kong to raise its rarely used No. 10 signal, ground 400 flights on Hong Kong airport and strand 80,000 travellers in a single day. Yet severe tropical storm Wipha’s story is bigger than toppled bamboo scaffolds and flooded rice fields. The storm’s rapid intensification, billion-dollar disruptions and widening geographic reach all echo the scientific fingerprint of human-driven climate change.

Meteorology of Typhoon Wipha in 2025

Typhoon Wipha began east of the Philippines in mid-July and wasted little time gathering strength over the warm waters in the South China Sea. By the morning of July 20, it had become powerful enough for the Hong Kong Observatory to raise its rarely used hurricane Signal No. 10. This is the city’s highest warning, issued only when hurricane-force winds are expected. Over the next seven hours, gusts reached 167 km/h, and more than 110 mm of rain fell on the territory, forcing officials and Hong Kong’s airport authority to shut down most public transport and aviation operations.

After skirting Hong Kong, Wipha made landfall near Taishan in Guangdong late on the same day, then weakened as it tracked westward toward Vietnam and Laos. Although its winds tapered quickly once over land, the system continued to unload torrential rains that primed rivers for flooding hundreds of kilometres inland.

Meteorologists were not surprised by typhoon Wipha’s rapid intensification or by the latitude at which it peaked. Sea-surface temperatures in the western South Pacific have warmed by approximately 0.4°C per decade since 1980, which is three times faster than the global average. Additionally, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change notes a very likely poleward shift in the zone where typhoons now reach their maximum strength.

In plain language, storms like Wipha are trapping more ocean heat, becoming stronger and moving farther north than they did a generation ago. This trend raises the stakes for densely populated coastal cities from Hong Kong to Shanghai.

Human and Economic Impacts of Severe Tropical Storm Wipha

Even though forecasting and model predictions were reasonably accurate, the tropical storm Wipha had major impacts across the region.

Hong Kong and Guangdong

In Hong Kong, the deluge dumped 110 mm of heavy rain in just three hours, felled 471 trees and injured 26 people. About 400 flights were rescheduled, and ferry as well as rail links were suspended, freezing mobility across the city. Early estimates suggest that direct economic losses could reach up to USD 255 million for a single day.

Across the border, Guangdong’s emergency office reported localised flash floods and restricted travel.

Vietnam, Laos and Thailand

Wipha’s second landfall near Nghe An, Vietnam, proved deadlier. Floods killed three people, submerged 3,700 homes and destroyed 16 square km of rice. As the storm weakened to a depression over Laos, swollen tributaries triggered major floods and landslides across the country.

In Thailand, the storm’s remnants merged with the southwest monsoon. Floods and landslides spanned 12 Thai provinces, affecting over 74,000 households and claiming six lives.

Climate Change and Intensifying Typhoons

Typhoon Wipha’s strength mirrors a wider pattern of increasingly extreme weather events as a direct result of climate change.

First, the number of rapidly intensifying tropical cyclones in the western North Pacific has almost doubled since the 1970s, with a sharp increase after 2002. One of the likely reasons for this shift is that the North Pacific has warmed faster than any other ocean basin since 2013. During this period, it has endured two multi-year “marine heatwaves” and baseline surface temperatures were well above average in July 2025.

Beyond increasing wind speeds, the warmer water also increases rainfall. It is estimated that for each degree of warming, cyclone rain rates increase by about 7%. Scientists remain divided on whether the total number of storms is increasing. Still, there is a broad consensus that their average intensity is rising, even if the frequency trends remain unclear.

Climate Action

The most effective approach to combat this issue is a dual approach of cutting emissions and adapting existing infrastructure and ecosystems.

Mitigation Strategies: Emissions Reductions

Trimming the risk of typhoons like Wipha starts with mitigation. This is encapsulated by the Paris Climate Agreement, which has been signed by 98% of the world and targets keeping warming below 2 °C, and ideally below 1.5 °C. Slowing or limiting the release of greenhouse gases (which is the primary source of warming) will reduce the intensity of storms.

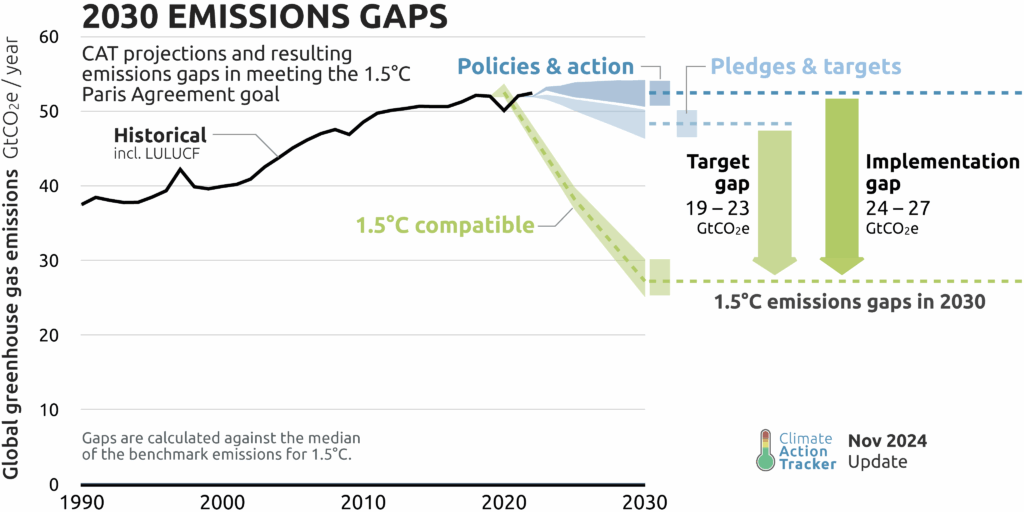

However, the world is currently not on track. The UNEP Emissions Gap Report 2024 warns that global greenhouse gas emissions must decrease by 42% by 2030 and 57% by 2035 to keep the 1.5°C goal alive. This is highly dependent on the rapid scaling of solar and wind energy. In Southeast Asia alone, the International Energy Agency calculates that installed renewables would have to rise to well over 400 GW by 2030, roughly double current growth rates, to align with that pathway.

Without effective mitigation, it is impossible to slow or stop climate change, and its extreme impacts will only intensify.

Adaptation Strategies: Building Resilient Communities

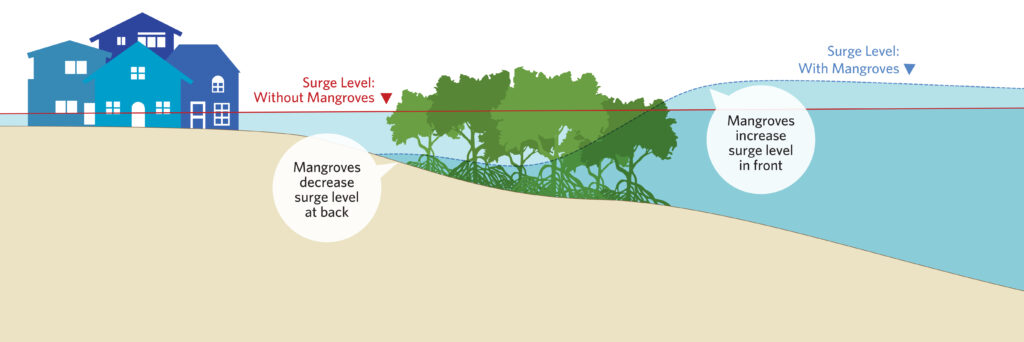

Because warming is already ongoing, equally urgent is adaptation. One excellent approach is the use of nature-based strategies, which often give some of the best returns. For example, mangroves are crucial to shoreline ecosystems, preventing more than USD 80 billion a year in coastal flood damage and protecting 18 million people. Preserving and restoring mangroves delivers benefits up to 10 times larger than the costs of restoration.

Communication and research infrastructure also pays dividends. The World Meteorological Organization finds that issuing a disaster warning 24 hours in advance can reduce disaster losses by 30%. However, one-third of the global population still lacks an early warning system. Investing in early warning systems would avoid global losses of USD 3-16 billion and save millions of lives.

Wipha’s lesson is stark: without deeper emissions cuts, disaster preparedness and resilient infrastructure, the toll of disasters will only increase.

The Call for Climate Finance

While most of the world recognises that mitigation and adaptation are both crucial for climate action, they are an expensive proposition. Even more challenging is that the most at-risk countries in the world are also some of the poorest and least developed.

This triple challenge means that it is nearly impossible for these highly at-risk countries to adapt to the impacts that they largely did not create and transition to renewables at the rate needed.

As a result, closing this finance gap falls on the shoulders of the private sector and developed countries. While the developed world reached its USD 100 billion annual funding goal in 2022 (two years late), the recently updated New Collective Quantified Goal (NCQG) from COP 29 sets a USD 300 billion yearly goal by 2035.

While this is a good step, it is just a fraction of the financing they really need. The developed world must take efforts seriously and push to the larger USD 1.3 trillion target. Failure to do so will result in millions of lives lost, billions of dollars in costs and unknown consequences for global society in the future.

Eric Koons

Writer, United States

Eric is a passionate environmental advocate that believes renewable energy is a key piece in meeting the world’s growing energy demands. He received an environmental science degree from the University of California and has worked to promote environmentally and socially sustainable practices since. Eric has worked with leading environmental organisations, such as World Resources Institute and Hitachi ABB Power Grids.

Eric is a passionate environmental advocate that believes renewable energy is a key piece in meeting the world’s growing energy demands. He received an environmental science degree from the University of California and has worked to promote environmentally and socially sustainable practices since. Eric has worked with leading environmental organisations, such as World Resources Institute and Hitachi ABB Power Grids.