At the CERAWeek conference in early March 2024, Amin Nasser, Saudi Aramco’s president and CEO, doubled down on the need to invest in fossil fuels. “We should abandon the fantasy of phasing out oil and gas and instead invest in them adequately,” he said in Houston, Texas. A round of applause followed.

Meanwhile, outside the venue, climate activists protested against the efforts of the oil and gas industry in continuing to fuel the climate crisis.

The three months before the conference reportedly became the hottest in history, breaking the 1.5°C mark by a significant margin.

Oil bosses’ calls to continue burning fossil fuels come after concentrations of the main greenhouse gases reached record-high levels in 2023, and scientists warned that climate records are “tumbling like dominoes”.

The prospects are that the 1.5°C target will soon be out of reach. At that point, we would enter uncharted territory. The question now is, at what point will that happen? And, more importantly, how will the world assist frontline communities in dealing with a problem that they didn’t create in the first place?

2023: The Hottest Year in History So Far

The past year broke temperature records worldwide, becoming the hottest 12-month period in the past 125,000 years.

Between January and November 2023, the world’s average temperature was 1.46°C higher than pre-industrial levels.

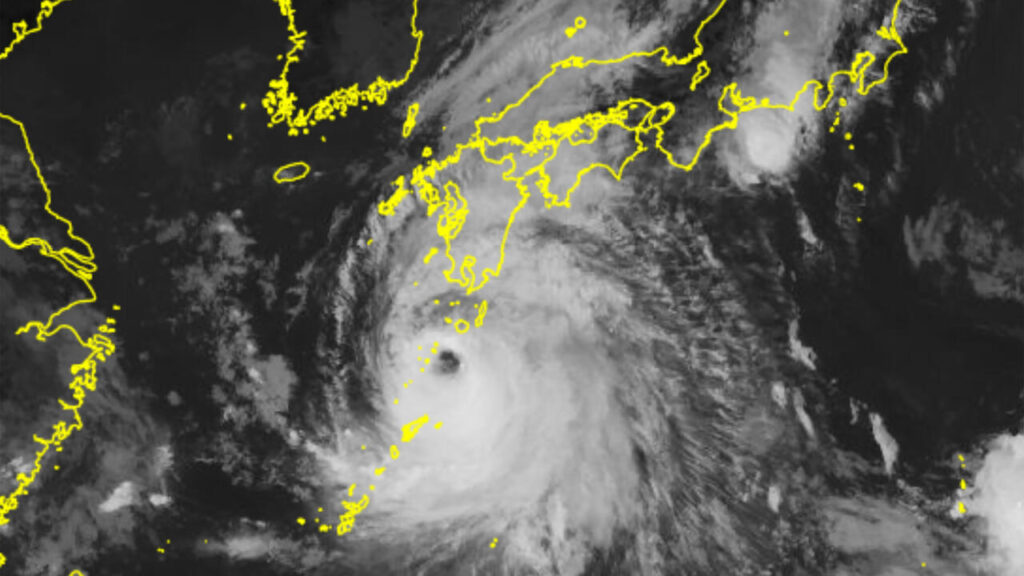

Extreme temperatures affected over 99% of humanity. However, Asia was among the regions suffering the harshest consequences, including intense and extended heatwaves, droughts and extreme rainfall. Many countries had to battle with the most extensive heatwaves in their history. Nearly every resident of Japan, Indonesia, the Philippines, Vietnam and Bangladesh suffered from extreme heat. No country was left unaffected, with regions in Japan, Indonesia, the Philippines, Vietnam, Bangladesh, India, China, Thailand and Laos all suffering from one or more extreme weather impacts. Among them were heatwaves, floods, droughts, wildfires and rapidly intensifying tropical cyclones. The weather abnormalities exacerbated existing problems like food security, air pollution, population displacement, loss of livelihoods and more.

The average global temperature breached the 1.5°C limit in about a third of the days throughout 2023. According to Copernicus, for the first time ever, every day within a year exceeded 1°C above pre-industrial levels. Close to 50% of the days were over 1.5°C warmer than the 1850-1900 period.

The World Meteorological Organisation found that the global mean sea level reached a record high. The rate of sea level rise between 2014 and 2023 more than doubled since the first decade of recording, 1993–2002. Antarctic sea ice extent reached an absolute record low in February. Glaciers experienced the most significant ice loss ever.

2024: More of the Same, or Worse?

A Carbon Brief analysis of four temperature projection models concludes that 2024 is likely to overtake the past year as the hottest in history, with a small margin of increase.

The first signs show they are on the right track. January was 1.66°C warmer than the pre-industrial period, February 1.77°C warmer and March 1.68°C warmer. The period became the hottest respective months in history, marking a period of ten consecutive record-breaking months.

Scientists: Heading Towards Uncharted Territory

The period between February 2023 and January 2024 breached 1.5°C, becoming the highest 12-month global temperature average on record. However, some scientists warn that 2024 might be humanity’s first full year beyond 1.5°C.

Such a move is likely to be temporary for several reasons. First, there is historical evidence that the year after the development of an El Niño event is warmer than the one in which it developed. Next, the Paris Agreement aims to keep global temperatures below the 1.5°C limit over the long term, usually a 20 or 30-year average rather than a single year.

These aren’t reasons for relief, though.

The more individual days that break the 1.5°C mark, the closer the world gets to breaching this mark in the longer term. According to NASA, before 2023 became the hottest in history, the world experienced nine consecutive warm years. This clearly highlights the worrying trajectory of global temperature rise we are on.

Copernicus notes that reaching 1.5˚C in global warming isn’t a distant reality. According to climate models, if the warming trend over the past 40 years continues, average temperatures will likely pass 1.5°C in the early 2030s. We are likely to surpass 2°C by around 2050.

However, we shouldn’t wait a decade or two to see when we will breach the target and by how much. The window to act on climate change is closing rapidly.

Climate scientists consider staying below 2°C, let alone 1.5°C, a long shot. To put the temperature increase into perspective, Reinhard Steurer, a climate researcher at the Vienna’s University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences, explains that 1.5°C means a climate we can adapt to and manage the consequences for, while 2°C is really dangerous. At 3°C, we can expect the collapse of civilisation, he warns.

Based on current policies, the world is heading towards 2.5°C-2.9°C in warming. According to the Lancet Countdown, a temperature rise of 2°C by 2100 will cause a 370% increase in annual heat-related deaths by 2050. Southeast Asia will be among the most affected regions.

Urgent and Deep Emissions Reduction Crucial to Change Course

Scientists raised the alarm about climate change over 200 years ago. The oil industry has known about the risks of its activities since the 1950s. The recipe for taming the climate crisis has been known for decades already. In a 1975 paper, the economist William Nordhaus, for example, proposed reducing greenhouse gas emissions like CO2 to negate the effects of global warming.

Fifty years later, the debate about taming the climate crisis is ongoing, and emissions continue to rise. According to the State of Climate Action 2023 report, only one of 42 climate action indicators is on track to achieve 2030 targets. Moreover, the authors note that some indicators are heading “in the wrong direction entirely.”

Researchers warn that to have even a 50:50 chance of achieving 1.5°C at the current emissions rate, we would have around six years to get to net zero.

A more realistic scenario is halving emissions by 2030 through halting the continued burning of coal, oil, and natural gas.

“Humanity’s actions are scorching the Earth. 2023 was a mere preview of the catastrophic future that awaits if we don’t act now. We must respond to record-breaking temperature rises with path-breaking action,” says UN chief António Guterres.

The UN’s climate chief, Simon Stiell, called on governments, business leaders and development banks to step up and help avert a worsening climate crisis, warning that the world has just “two years to save the planet“.

Fortunately, we have all the tools to limit emissions, and they have never been cheaper, more efficient or easily deployable. The NDC updates in 2025 offer a prime opportunity to leap forward with more ambitious policy support.

What’s Next?

During the CERAWeek conference, oil bosses argued that the climate debate has become “emotional,” making it more difficult to reach a “pragmatic solution”.

Climate change’s impacts might not seem so harsh for those sitting in boardrooms or looking at balance sheets, but they do for the 800 million South Asians living in extreme weather hotspots, or the almost 63 million could be displaced by 2050 due to crop failure or rising sea levels.

“Honestly, I don’t know how to cope with climate change. The biggest concern is that I’m losing hope that things will get better,” shares Jeongyeong Kim, a farmer from Sangju in the North Gyeongsang Province of South Korea. Flash floods destroyed her farm in the summer of 2023.

“I don’t have a religion, but I still prayed for it to stop raining,” adds Hwayoung Yoo, another farmer from Nonsan, South Korea, on account of last summer’s weather disaster. “The water level reached to my waist. I had never been so desperate for my entire 53-year life.”

When hearing the stories of frontline communities, the climate debate can, indeed, get emotional. However, the arguments behind it are rational and have long been made clear by the world’s best climate scientists and leading energy agencies. For 28 COP conferences and counting, those with the biggest power to mitigate the climate catastrophe have failed to adequately address these warnings. COP29 is the next best moment, and leaders should make it count.

Heading into the conference, everyone should keep in mind that the Paris Agreement is a human rights treaty, and opting to continue fueling the climate crisis can be seen as a human rights violation.

Viktor Tachev

Writer, Bulgaria

Viktor is a writer that specialises in green finance and ESG investment practices. He holds a Master's degree in financial markets and has over a decade of experience working with companies in the finance industry, along with international organisations and NGOs. Viktor is a regular contributor to several publications and comments on the likes of sustainability and renewable energy.

Viktor is a writer that specialises in green finance and ESG investment practices. He holds a Master's degree in financial markets and has over a decade of experience working with companies in the finance industry, along with international organisations and NGOs. Viktor is a regular contributor to several publications and comments on the likes of sustainability and renewable energy.