Tokyo’s air quality is often described as relatively good for a global megacity, but the data tells a more complicated story. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), air pollution remains one of the leading environmental health risks worldwide, even in high-income countries with strong regulatory systems. In Tokyo, decades of regulation have reduced some of the most visible forms of pollution. Yet, millions of residents are still exposed to levels of pollutants that exceed health-based guidelines.

For decision-makers focused on sustainability, health and climate resilience, Tokyo offers a useful case study. Smog events no longer define the city’s air pollution, but its residents can be affected by chronic exposure linked to transport, energy use and climate change.

Japan Air Quality Monitoring – How Is Air Quality Measured in Tokyo?

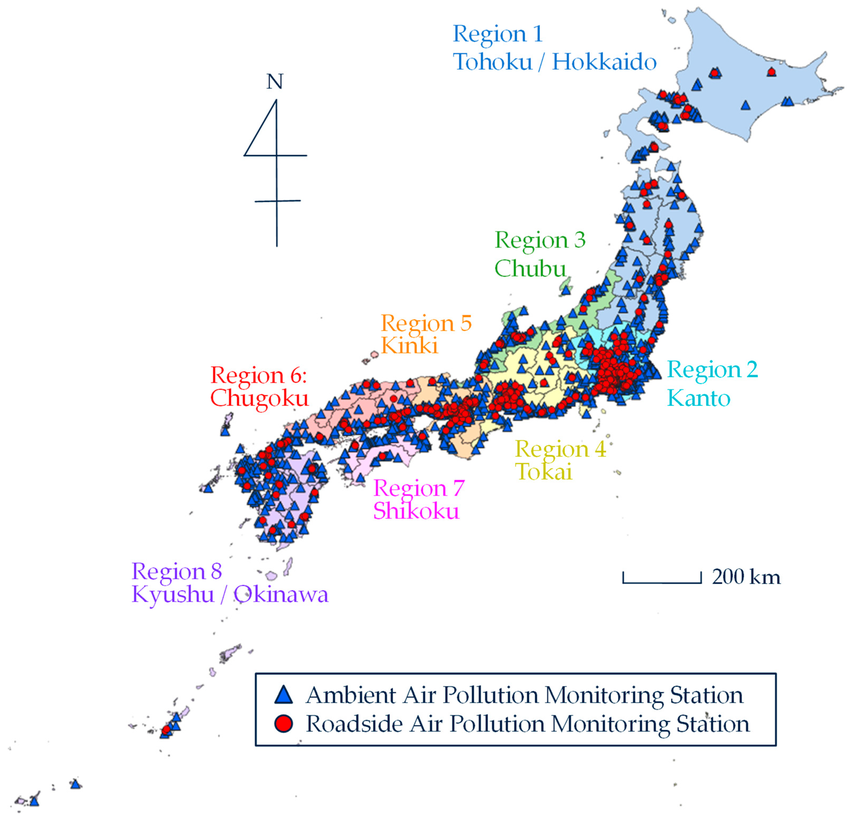

Air quality in Japan is monitored through a national system overseen by the Ministry of the Environment. The ministry sets pollutant standards and regulates how monitoring results are evaluated. In Tokyo, the Tokyo Metropolitan Government publishes real-time measurement results from its air monitoring stations, which operate 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. Nationally, Japan’s continuous monitoring system covers multiple pollutants and includes two main station types: general ambient stations and roadside stations designed to track vehicle-related pollution.

Key Pollutants, Nitrogen Dioxide, Carbon Monoxide Tracked in Tokyo

Fine particulate matter, especially PM2.5, is one of the most critical pollutants tracked in Tokyo due to its strong links to cardiovascular disease, respiratory illness and premature mortality. Nitrogen dioxide from vehicle exhaust, ground-level ozone formed through atmospheric reactions and carbon monoxide from incomplete combustion are also monitored. These pollutants are closely associated with traffic density, fuel combustion and urban energy demand rather than isolated industrial sources.

How Bad Is the Air Pollution in Tokyo?

Based on 2019 data compiled by IQAir, Tokyo’s annual average PM2.5 concentration was approximately 11.7 micrograms per cubic metre. This is substantially lower than many Asian megacities, but still more than double the WHO’s recommended guideline of 5 micrograms per cubic metre for long-term exposure.

Epidemiological evidence shows that health risks increase even at relatively low concentrations, especially with continuous exposure over many years. As a result, Tokyo air quality is often classified as “moderate,” but moderate does not equate to little or no risk.

Tokyo’s Current Air Quality Ranking and Recent Trends

In global rankings, Tokyo consistently performs better than many cities in East and South Asia. IQAir ranked Tokyo 3,129th among 8,954 cities tracked between 2017 and 2024 for air quality.

This reflects significant improvements since the early 2000s, driven by stricter vehicle standards and cleaner fuels. However, multiple long-term analyses show that these gains slowed after the initial decline. PM2.5 concentrations have changed only modestly in more recent years rather than continuing to fall sharply.

Seasonal pollution spikes also persist, particularly in winter. In winter, weak winds and atmospheric stagnation limit dispersion, allowing locally emitted pollutants to accumulate.

What Drives Air Pollution in Tokyo?

A combination of local emissions and regional transport of pollutants shapes Tokyo’s air pollution. In the Greater Tokyo Area, the region’s intense human activity means air pollution from road traffic is a major contributor to local air quality outcomes. At the same time, long-range transport across East Asia can influence Japan’s urban background levels.

Urban Transport and Energy Use

Japanese monitoring and traffic data show a clear relationship between traffic volume and ambient concentrations of nitrogen oxides, sulfur dioxide and carbon monoxide, particularly along major urban corridors. While vehicle standards have tightened, overall travel demand remains high. Energy use also matters upstream. Japan’s electricity supply is still largely fossil-fuel based, with coal and natural gas together providing around 60% of generation, linking urban energy demand to combustion-related emissions.

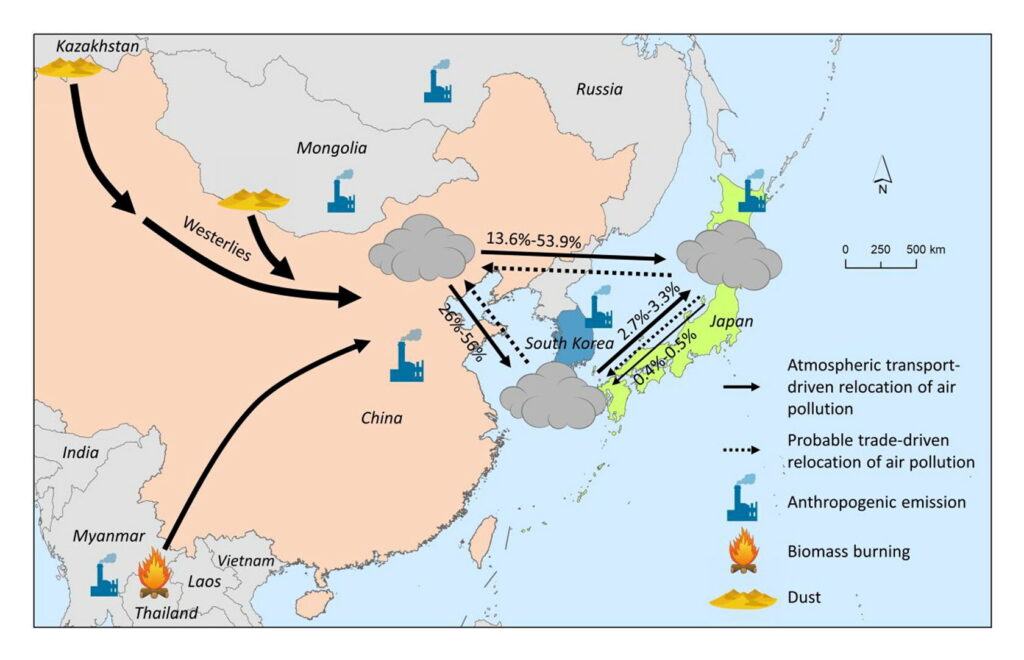

Transboundary and Regional Pollution

Long-range transport of PM2.5 into Japan is well documented. Prevailing westerly winds can carry fine particles from other parts of Asia, influencing background pollution levels even in cities with strong local controls. These transboundary contributions can raise baseline concentrations, making it harder to achieve further local air quality improvements without regional emissions reductions.

Health and Social Impacts of Tokyo Air Pollution

The most serious impacts of Tokyo air pollution come from long-term exposure, not just “bad air days.” The WHO links ambient air pollution to higher risks of cardiovascular disease, stroke, chronic respiratory disease and lung cancer. These impacts accumulate over time rather than showing up only during short spikes. These risks are not evenly shared, as children, older adults and people with existing illnesses are more vulnerable.

Health Risks Linked to Fine Particulate Matter

PM 2.5 is especially harmful because it can penetrate deep into the lungs and enter the bloodstream. Estimates attribute around 7.8 million premature deaths annually to PM2.5 air pollution. The State of Global Air 2024 report also places PM2.5 among the leading global risk factors. This reinforces that “moderate” concentrations can still drive meaningful health burdens.

Economic and Social Costs

Air pollution’s costs show up in healthcare spending, productivity and reduced quality of life, even in high-income settings. Combined, these impacts are estimated to cost Tokyo USD 43 billion annually and Japan as a whole USD 110 billion annually.

What Is Being Done, and What Gaps Remain?

Japan’s air quality policy framework has delivered substantial long-term improvements, particularly through national emissions standards and transparent monitoring. According to Japan’s Ministry of the Environment, many traditional pollutants have declined over time, reflecting the cumulative impact of regulatory controls. However, official assessments continue to flag nitrogen dioxide, suspended particulate matter and photochemical oxidants as unresolved issues, especially in large metropolitan areas where population density and daily activity concentrate emissions.

The challenge now is structural rather than regulatory. Remaining pollution is closely tied to everyday mobility, freight movement and energy consumption, making incremental gains harder to achieve. This is compounded by Japan’s electricity system, which heavily relies on fossil fuels. As a result, further improvements in air quality increasingly depend on broader progress in the energy transition and sustained coordination across transport, power and urban planning systems.

Eric Koons

Writer, United States

Eric is a passionate environmental advocate that believes renewable energy is a key piece in meeting the world’s growing energy demands. He received an environmental science degree from the University of California and has worked to promote environmentally and socially sustainable practices since. Eric has worked with leading environmental organisations, such as World Resources Institute and Hitachi ABB Power Grids.

Eric is a passionate environmental advocate that believes renewable energy is a key piece in meeting the world’s growing energy demands. He received an environmental science degree from the University of California and has worked to promote environmentally and socially sustainable practices since. Eric has worked with leading environmental organisations, such as World Resources Institute and Hitachi ABB Power Grids.