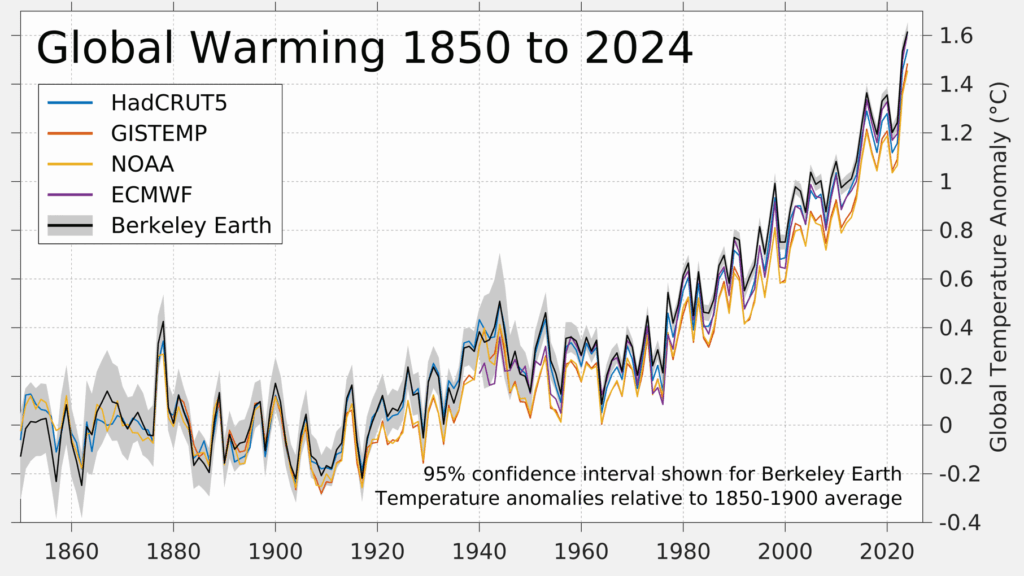

Why is climate change bad? In 2024 we crossed a historic threshold: the first calendar year with a global average temperature more than 1.5°C above the 1850–1900 preindustrial baseline. The UN’s World Meteorological Organization, the EU’s Copernicus programme and NOAA all found the same outcome: an average global temperature increase of about 1.55°C.

That does not mean the Paris Agreement’s 1.5°C goal has been formally “breached” because the treaty judges success on multi-decade averages, not a single year. However, it is a stark warning that the window for avoiding sustained 1.5°C warming is narrowing fast.

What the Science Shows Today

Rising Temperatures and Heat Waves

Zooming out shows the longer-term global temperature trend. 2015 to 2024 was the warmest decade on record, with every year since 2015 among the top 10 warmest. Long-term datasets show the rate of warming has accelerated to above 0.2°C per decade, more than double the 20th-century pace.

That background warming increases the likelihood of more frequent and intense heat extremes and other weather events, both of which are high-confidence findings in the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC’s) Sixth Annual Report.

In short: the climate is not fluctuating around a stable mean. It’s shifting to a hotter, more volatile state.

Oceans, Ice and a Shifting Water Cycle

Sea levels continue their relentless climb as oceans store the vast majority of excess heat. Satellite images show over 10 cm of global mean sea-level rise since 1993, amplifying coastal flood risk across the world. This is particularly relevant in Asia, where large population centres sit in low-lying coastal areas.

At the same time, hydrological extremes are intensifying. A warmer atmosphere holds more moisture, increasing heavy rainfall in some regions and longer dry spells in others. This raises baseline risks for cities, river basins and agriculture.

Natural Environments Under Strain

Climate change is reshaping nature on land and in the water. In the oceans, back-to-back marine heatwaves triggered the fourth global mass coral bleaching event. The event has affected 84% of global reef areas and is undermining fisheries, coastal protection and tourism.

On land, the impact on biodiversity is extreme. Wildlife populations have fallen by more than 70% since 1970, reflecting habitat loss compounded by rising heat, drought and shifting seasons. Furthermore, research warns that parts of the Amazon could face unprecedented combinations of drought, heat, deforestation and fire by mid-century, raising the odds of regional ecosystem shifts with global climate feedbacks.

How Global Climate Change Harms People and Economies

Health Impacts of Global Warming

Heat is already the deadliest weather hazard. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that heat-related mortality among people aged 65 and over rose 85% between 2000 and 2021. This led to almost 550,000 heat-related deaths per year (2021 to 2021), a 23% rise from the 1990s. And climate change will continue to bring more frequent and intense heatwaves.

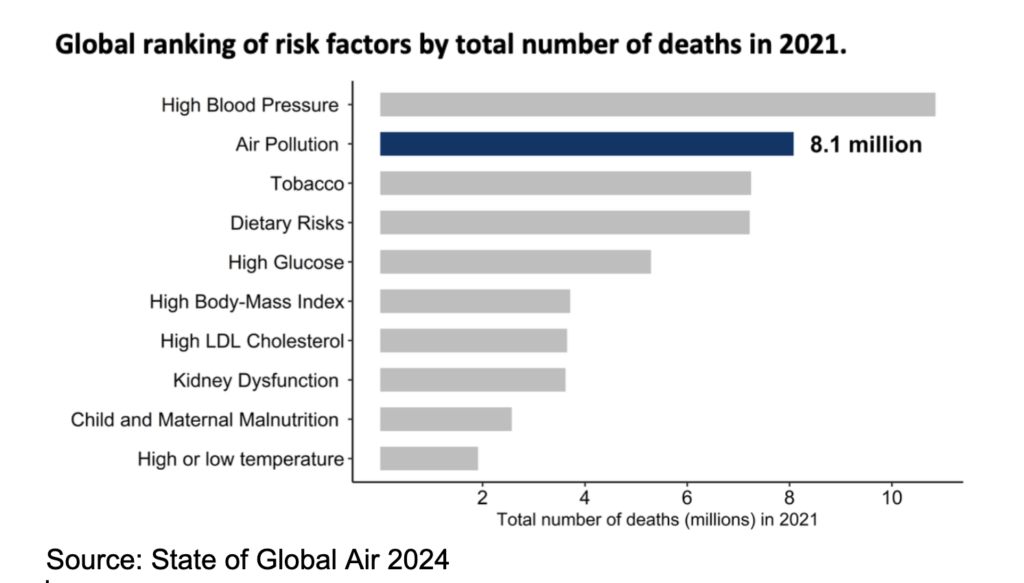

At the same time, the secondary impacts of climate change also hold major health risks. For example, air pollution accounts for over 7.9 million premature deaths annually, extreme weather events cause up to 50,000 deaths annually and infectious diseases are spreading.

Food, Water and Infrastructure

Climate shocks are squeezing basic systems. In 2023, 733 million people faced hunger and 2.33 billion experienced moderate or severe food insecurity as heat, floods and drought disrupted harvests and markets. Water risk is also widening. Around 2.4 billion people live in water-stressed countries, a figure expected to rise without significant investment.

On the economic side, infrastructure damage is increasing each year. Global disaster losses totalled about USD 368 billion in 2024, driven primarily by hurricanes and severe storms. These intertwined impacts raise prices, strain public budgets and slow growth.

Where Vulnerability Concentrates and Why Asia Stands Out

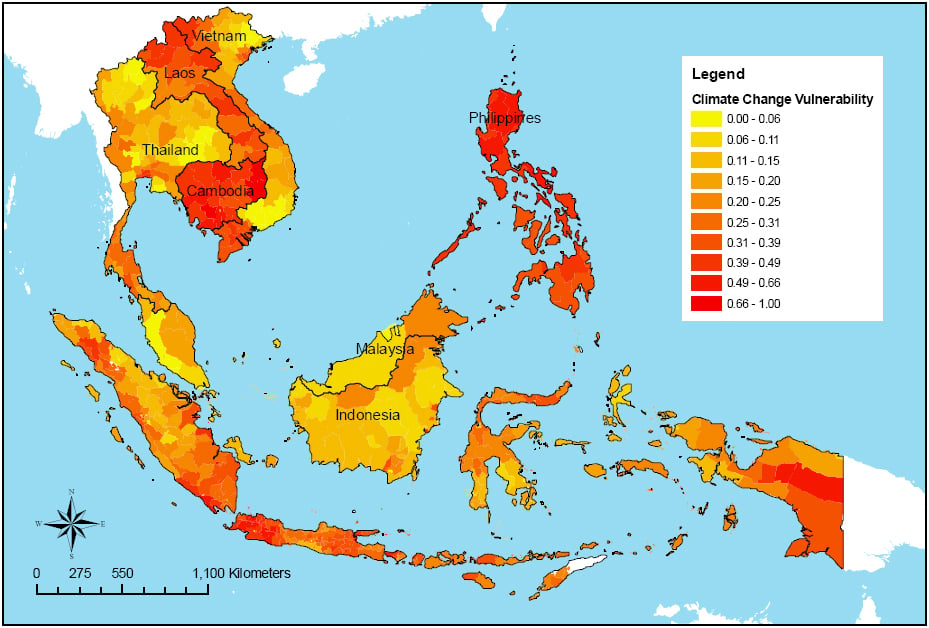

Globally, risk clusters in low lying coastal areas and river deltas, as well as arid and semi-arid interiors and small island states. High-risk regions are present across the world, with the highest concentration along the equator and at high latitudes.

This puts Asia right in this high-risk zone and the region’s coastal exposure is immense. Bangladesh, China, India, Indonesia, Thailand and Vietnam are all projected to have significant land areas below average annual flood levels by 2050. Added to this, the region is warming faster than the global average and is experiencing increasingly severe extreme weather events like typhoons.

For example, over 750 million South Asians have experienced at least one major flood, drought or cyclone in the past two decades. As a result, annual climate change losses are projected to exceed USD 160 billion by 2030.

These concentrated risks are colliding with a worsening adaptation finance gap. International public flows totalled USD 26 billion in 2023, against estimated annual needs of over USD 300 billion. This remains a major hurdle for climate progress and continues to be a central point of discussion in international climate talks.

What To Do Next: Scale Mitigation, Scale Adaptation

Addressing human-caused climate change requires a two-sided approach. Accelerate mitigation like clean energy and efficiency to limit carbon dioxide emissions now and scale proven adaptation where exposure is highest. Doing both delivers immediate health and economic benefits while lowering long-term risk.

Mitigation: Cut Emissions Fast, Unlock Co-Benefits

Clean energy is scaling, but not yet fast enough. In 2024, global energy investment topped USD 3 trillion, with two-thirds of that going towards clean technologies. Spending on renewables, grids and storage now exceeds fossil investment.

Record deployments continued in 2024, with a 15% increase in global renewable energy capacity (585 GW) and a 25% increase in electric vehicle sales (17 million). These shifts cut more greenhouse gas emissions and air pollution while improving energy security.

However, to align with COP28’s “tripling” ambition, renewable energy growth must accelerate to add 11.2 TW of capacity annually. Reaching this target would limit the worst effects of climate change.

Adaptation: Protect People and Places Now

Even if this target is reached, the world will still need to adapt to the inescapable impacts of climate change we are already seeing.

Priority investments are well known. Early-warning systems remain the highest-return investment in disaster risk reduction, delivering nearly a 10-fold ROI while saving lives and cutting losses when heat, flood or storm hazards escalate. In cities, heat adaptation hinges on shade, evapotranspiration and better planning. Just raising tree cover toward 30% cools urban air and can avoid thousands of heat-related deaths each summer.

Along coasts, nature-based protection scales resilience and carbon benefits together. Global assessments find mangroves protect over 6 million people annually and avoid USD 24 billion in asset losses each year, while national programs, such as Indonesia’s restoration projects, show how to embed these defences in development.

Eric Koons

Writer, United States

Eric is a passionate environmental advocate that believes renewable energy is a key piece in meeting the world’s growing energy demands. He received an environmental science degree from the University of California and has worked to promote environmentally and socially sustainable practices since. Eric has worked with leading environmental organisations, such as World Resources Institute and Hitachi ABB Power Grids.

Eric is a passionate environmental advocate that believes renewable energy is a key piece in meeting the world’s growing energy demands. He received an environmental science degree from the University of California and has worked to promote environmentally and socially sustainable practices since. Eric has worked with leading environmental organisations, such as World Resources Institute and Hitachi ABB Power Grids.