Nestled between eight coal power plants is Jakarta, the capital of Indonesia. The wind direction often changes during the dry season, blowing pollutants from the coal plants toward the city. Paired with the traffic and industrial emissions, they form a harmful cocktail, spreading all over the city landscape.

In August 2023, Jakarta topped the global ranking for the worst air quality, with the concentration of fine particulate matter reaching 19 times the WHO’s recommended levels. The Ministry of Environment and Forestry responded to the situation by telling residents to “pray for rain”, causing a large backlash on social media. Since prayers didn’t help and rain didn’t come, the government halved the output at one of the nearby coal plants.

In 2022, coal-fired power plants caused 10,500 deaths in Indonesia. According to a joint study by the Institute for Essential Services Reform and the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air, if they continue to operate, the death toll could soar to 180,000 by 2040.

Estimates reveal that in 2022, the health costs of coal-fired power plants in Indonesia reached USD 7.4 billion. At the same time, cleaning up one coal power plant near Jakarta could help Indonesia avoid USD 1 billion annually in preventable deaths, medical bills and work absences.

Yet, the response to the glaring environmental and health crisis is slow and stalling, while vested industry interests risk making fossil fuels an integral part of Indonesia’s future.

Indonesia’s Fossil Fuel Obsession

Indonesia is the world’s largest global thermal coal exporter and third-largest coal producer. Its coal reserves are expected to last for at least another 60 years. Domestically, fossil fuels account for around 80% of Indonesia’s electricity generation, with coal holding a 61.5% share.

The country operates 118 coal plants with an average age of less than 15 years compared to the 40-year typical lifespan of a coal power plant. Moreover, Global Energy Monitor notes that as of the end of 2022, Indonesia had 18.8 GW of coal power under construction – nearly half of its current capacity and more than most other countries, except China and India.

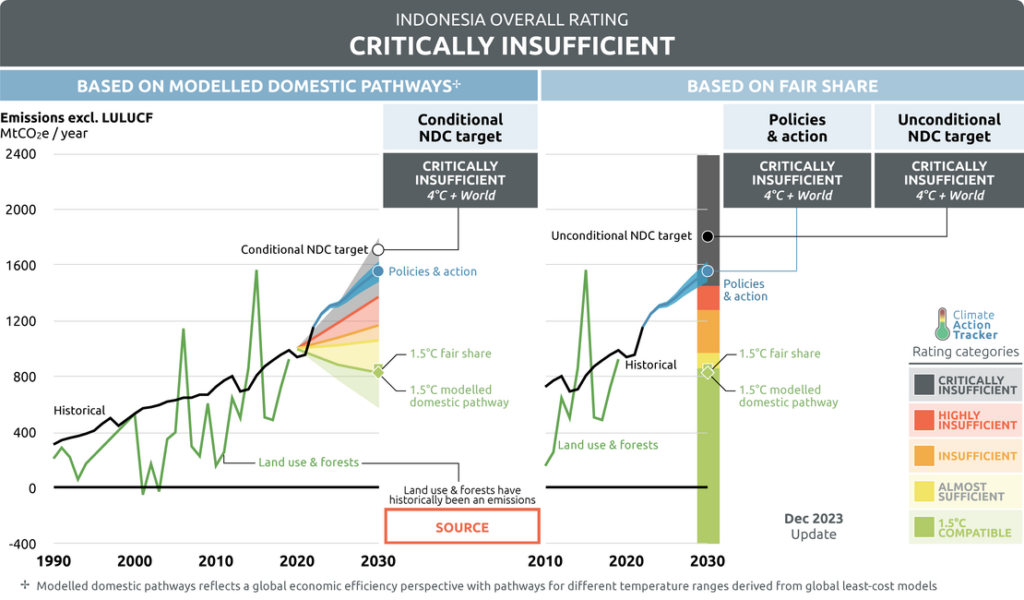

According to Climate Action Tracker (CAT), Indonesia’s new plans could elevate total power sector emissions to 400 MtCO2 in 2030. This would be more than twice the level required to align with the Paris Agreement’s temperature limit. The huge fleet of newly operating coal plants has already increased Indonesia’s emissions by 21% in 2022. The country is among the worst performers in CAT’s rankings, with a “critically insufficient” rating for its climate targets and policies. In fact, the result is a grade lower compared to the organisation’s previous assessment.

Alongside other Southeast Asian countries, Indonesia will also lead the global gas expansion.

Throwing Fuel on the Fire of Climate Change

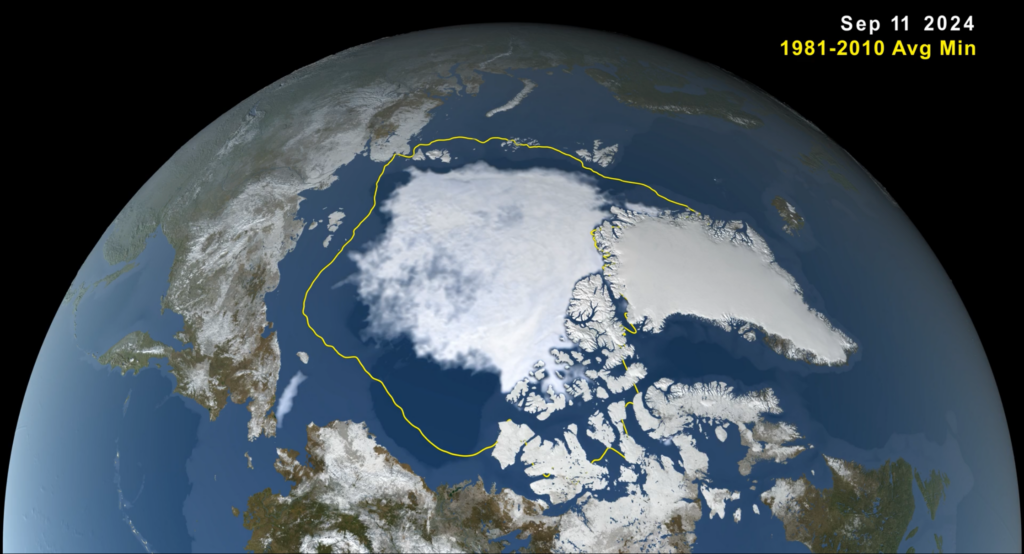

The year 2023 is expected to be recognised as the hottest on record. The world experienced six consecutive months (June-November) of record-breaking temperatures. According to scientists, the 2023-2027 period will almost certainly be the warmest five-year period ever.

Climate Action Tracker notes that if all countries were to follow Indonesia’s climate targets and policies, warming would exceed 4°C. Although Indonesia is on the climate change front line, its weak climate commitments are putting it on a self-destructive trajectory.

Meanwhile, according to Swiss Re, global warming of 2.0-2.6°C by 2050, which is where the world is heading currently, will shrink Indonesia’s GDP by up to 30.2% due to climate change impacts. The Global Climate Risk Index ranks Indonesia 14th among 181 countries, and the country faces high exposure to all types of flooding and extreme heat.

Furthermore, Indonesia has the fifth-biggest population inhabiting lower-elevation coastal zones globally, making it extremely susceptible to sea-level rise.

Jakarta, the nation’s capital, is the fastest-sinking city in the world. According to experts, authorities have until 2030 to figure out a solution. Otherwise, unabated sinking, intensifying storms and rising sea levels will prove too much for its seawalls. At the current rate, one-third of the city could be submerged by 2050. This prompted the government to start moving the country’s capital to the island of Borneo.

Indonesia is also among the most vulnerable countries to extreme heat waves. Without urgent emissions reduction, heat waves in Indonesia will last almost 8,000% longer by 2050.

Indonesia’s National Disaster Management Agency notes that floods, droughts, landslides, storms and cyclones have increased by 35% between 2021 and 2022.

At the same time, Indonesia’s response is lacking. It has fallen by 10 places to 36th in the Climate Change Performance Index for 2024. The Environmental Performance Index, assessing national efforts toward environmental health to enhance ecosystem vitality and mitigate climate change, ranks the country 164th out of 180 countries.

Indonesia Can Change Its Course Through Emissions Reduction and Its JETP

While avoiding climate change’s impacts altogether will be challenging, Indonesia still has time to avert and mitigate the worst of them. Doing so would require addressing the two main problems that brought the country to its current situation in the first place: high emissions from deforestation and the energy sector.

Addressing Deforestation

In the forestry sector, Indonesia is making some positive steps, including initiatives for restoring forests and peatlands and rehabilitating degraded land. That way, Indonesia can turn its forestry sector into a carbon sink and unlock untapped potential for reducing domestic emissions.

At COP28, Indonesia and Norway struck a USD 100 million partnership to support its pioneering FOLU Net Sink 2030 plan. The program will ensure that carbon sequestration from forestry and other land use exceeds or equals its overall emissions by 2030.

Slashing Energy Sector Emissions

The country’s plans for new coal and gas capacity development will lock it into a future of high emissions, elevated energy costs and increased air pollution. All this while ignoring the vast potential for scaling up cheaper, cleaner and quickly deployable energy sources like solar and wind.

According to TransitionZero, when accounting for air, water and climate costs, the average operating cost of coal is 27% higher than that of clean energy.

Contrary to belief, however, retiring the existing coal power plants won’t prove costly. TransitionZero finds that Indonesia could close all 118 coal plants by 2040 in line with the Paris Agreement at a total cost of USD 37 billion. For comparison, in 2021, Indonesia paid over USD 10 billion in coal subsidies. Furthermore, in 2022, the country had to budget USD 37.75 billion or 19.87% of its total 2022 expenditure for subsidies and compensation to keep most energy and fuel prices unchanged and protect consumers. According to the EU–ASEAN Business Council, this is twice Indonesia’s 2022 healthcare budget and four times its defence budget.

Furthermore, transitioning from coal to renewables can save between USD 15.6-51.7 billion per year when accounting for air pollution costs by 2030.

Meanwhile, polls reveal that Indonesians are not only on board with the clean energy transition but are also actively supporting it. The Southeast Asia Climate Outlook 2023 Survey Report by the Climate Change in Southeast Asia Programme at ISEAS reveals that most of the Indonesian respondents think their country should stop building new coal power plants immediately. In fact, Indonesian respondents are the strongest advocates of closing coal plants right away. The locals are also among the most supportive of a national carbon tax and among the most concerned about climate change in the region.

Making the Most Out of the JETP

The USD 20 billion Just Energy Transition Partnership mechanism, funded by developed countries and the private sector, aims to accelerate Indonesia’s decarbonisation journey.

Under the conditions of the JETP, Indonesia pledged to increase its clean energy generation target to 44% by 2030 and achieve net zero by 2050.

The first step to succeeding is prioritising investment projects with the greatest near-term benefits, like scaling up solar and wind power capacity. However, as per the government’s Comprehensive Investment and Policy Plan (CIPP), a roadmap clarifying Indonesia’s JETP-related green transition policy and decarbonisation needs, solar energy has the least number of projects mentioned. This is despite being the focus of domestic green manufacturing industry development and also having the lowest lifecycle cost. Furthermore, the CIPP also has loopholes regarding the extended use of coal for powering industry.

The JETP itself isn’t perfect. The financing is insufficient to meet Indonesia’s actual needs. Moreover, just 1.4% of it is in the form of grants, which risks burdening Indonesia with debt. Furthermore, according to the environmental think tank Ember, Indonesia’s JETP targets are 10 years too late for a 1.5°C-aligned pathway.

Yet, the JETP is a good start, and Indonesia’s government should use it as a stepping stone while at the same time working to introduce the needed market reforms to help attract additional private financing and accelerate its energy transition.

Leaving Coal In the Ground: The Key to a Healthier and More Sustainable Future For Indonesia

In 2021, President Joko Widodo’s administration announced an end to new coal-fired power plants after 2023. However, today, there is a growing momentum to make coal “green” in Indonesia’s taxonomy. For comparison, the EU’s taxonomy for sustainable activities excludes coal. The IEEFA notes that even China and Russia have kept coal and gas-powered generation out of their respective green taxonomies.

Furthermore, Indonesia’s JETP agreement now makes exemptions for captive coal plants. While the government has promised to address the matter at some point as part of its CIPP, when it will do so remains unclear.

Andri Prasetyo, researcher and program Manager for Trend Asia, says, “Indonesia’s JETP is overshadowed by the fact that the Indonesian government is still giving ambiguous market signals in the energy transition by not setting a clear deadline for new coal power construction, including allowing more than 13 GW of coal to enter the grid and 15 GW of captive coal power to power industries.”

Prasetyo adds: “In addition, the Indonesian government continues to expand fossil gas in the electricity grid, which will hinder the development of renewable energy.”

According to the IEA, limiting global warming to 1.5°C requires 60% of oil and gas reserves and 90% of coal reserves to remain unused.

Whoever holds power in Indonesia after the February elections will have to show the political will to overcome the strong fossil fuel lobby in the country. Doing so will be critical for the sake of the country’s economy, nature and, most importantly, the well-being of Indonesians.

Viktor Tachev

Writer, Bulgaria

Viktor is a writer that specialises in green finance and ESG investment practices. He holds a Master's degree in financial markets and has over a decade of experience working with companies in the finance industry, along with international organisations and NGOs. Viktor is a regular contributor to several publications and comments on the likes of sustainability and renewable energy.

Viktor is a writer that specialises in green finance and ESG investment practices. He holds a Master's degree in financial markets and has over a decade of experience working with companies in the finance industry, along with international organisations and NGOs. Viktor is a regular contributor to several publications and comments on the likes of sustainability and renewable energy.