For many living near coal plants in Banten province, Indonesia, the stormy-like grey skies, the ash film covering everything around and the feeling of smog entering their lungs have become an everyday reality.

It is all 26-year-old Sutrisno had ever known before leaving home to attend university in another province. Born in the shadow of the Suralaya Power Station, Southeast Asia’s biggest coal power complex, he is one of many whose lives have been intertwined with industrial and coal power plant pollution. While some have already left or were displaced, others stayed and are now suffering from respiratory diseases and seeing their income deteriorate due to lowered fish catches and agricultural yields.

These problems are about to worsen due to the upcoming expansion of the Suralaya Power Station. The Asian Development Bank is among those indirectly backing two new plants, Java 9 and Java 10.

While many locals are afraid to speak out due to fear of industry and government intimidation, Sutrisno has decided to use a pseudonym and tell his story for an investigation by the environmental and human rights groups Inclusive Development International, Recourse, the NGO Forum on ADB and Trend Asia on ADB’s indirect financing of coal plants in Indonesia.

“I decided to start speaking out. I didn’t want to remain silent anymore,” he explains, hoping that his community and the others affected by coal will finally be able to make a difference.

The Asian Development Bank Continues to Finance Coal Despite Climate Commitments, New Research Reveals

According to the report Smog and Mirrors: How “Sustainable” Finance from the Asian Development Bank is Fueling Indonesia’s Coal Expansion, the USD 600 million loan granted by the ADB to Indonesia’s state-run power company PLN in 2021 can support over a dozen coal expansion projects, part of PLN’s 10-year plan. Among them are Java 9 and 10, part of the plans to expand the Suralaya Power Station – Southeast Asia’s largest coal complex.

The ADB describes the loan as an effort to promote the use of clean energy. In an email to Inclusive Development International, an ADB spokesperson denied that the loan can be used for coal power plant financing.

However, the report’s authors have identified loopholes that prove otherwise. For example, the loan agreement doesn’t include any coal exclusion clauses. Even if it did, in practice, enforcing such a clause would be challenging since the funds will enter PLN’s general bank account, which would complicate tracing and verification, they explain. As per ADB’s own green financing standards, the provided financing should go into a separate account for transparency purposes, says the report.

“ADB’s loan agreement doesn’t just fail to exclude coal. If you look closely, it actually allows PLN to use ADB funding for coal-fired power plants,” explains Dustin Roasa, research director at Inclusive Development International and author of the report.

By funding polluting projects across Southeast Asia, one of the most vulnerable regions to climate change, the ADB violates its climate commitments, including a no-new-coal pledge, reaffirmed last year by its president, Masatsugu Asakawa. Furthermore, the institution is undermining the USD 100 billion in green financing promised as support for the development of clean energy projects and early coal plant retirement.

The Human Costs of PLN’s Coal Expansion Plans

In Indonesia, fine particulate matter (PM2.5) contributes to a staggering 94,000 premature deaths each year. Coal is responsible for around 13% of them.

Furthermore, the problem is worsening. Between 2010 and 2019, Indonesia experienced a 24.4% increase in deaths attributable to PM2.5.

People living in the Banten province of western Java don’t need statistics to tell them there is a problem. They have been living with the pollution from the Suralaya Power Station for 40 years already, and as things stand, they will have to continue doing so, but on a larger scale.

“That’s not rain, that’s coal ash,” explains Mad Haer Effendi, talking about the grey skies on the western coast of Java. As the head of Java‑based environmental advocacy organisation PENA Masyarakat, he is part of an increasing group of civil society activists, environmentalists and affected locals trying to resist the Java 9 and 10 projects through the courts, protests and campaigns.

Currently, pollution from coal plants in the region takes the lives of 2,500 Indonesians per year and causes or exacerbates health problems like respiratory diseases and cancer. Greenpeace estimates that the Java 9 and 10 expansion will cause between 2,400 and 7,300 premature deaths over an expected 30‑year lifespan.

Local communities and environmental advocates have been trying to push back against the projects through protests, campaigns, and filing complaints. However, opposing the expansion doesn’t come without its risks.

Locals have told the authors of the Smog and Mirrors investigation stories of thugs who threaten people speaking out about pollution or special military and police units coming into communities and asking coal opponents intimidating questions.

“Coal and heavy industry have been here so long that people have surrendered to it. There’s just so much of it — it’s everywhere you look. People think, what’s the point of trying to fight it?” explains Mad.

At the same time, the coal plants in the region and the processes around them continue to disturb locals’ livelihoods.

Mulyadi is the pseudonym of a fisherman interviewed for the Smog and Mirrors investigation. He explains that, over time, the catch has been dwindling, and it has become increasingly challenging to find fish near the coast due to the proximity to the power plant.

“Sometimes we go without food for a day or two,” he explains.

Aside from their livelihoods, Mulyadi’s family is fighting to preserve something even more important – the health of their daughter. Growing up near the Suralaya Power Station, she developed a chronic cough and difficulty breathing. Later, doctors diagnosed her with an acute respiratory infection.

According to estimates, up to 15,000 children under five years living in the area have suffered from the same condition.

Mulyadi said he doesn’t trust the developers of Java 9 and 10 to act responsibly due to their history of disregarding the needs of the locals. He says he is grateful for what his family has, even though they are struggling. “I just hope we can find a better balance between community and industry.”

New Coal Capacity Won’t Only Lock Indonesia Into a Future of Increased Emissions, It Will Have Global Implications

The stories of Sutrisno, Mulyadi and the thousands of Indonesians affected showcase the personal implications of a broader problem.

Indonesia is the sixth-biggest CO2 emitter globally. It is the world’s largest thermal coal exporter and third-largest coal producer. The country operates Southeast Asia’s largest coal-fired power plant fleet, with an average age of less than 12-13 years (compared to a typical lifespan of 40 years) and has a significant problem with captive coal power. Even more worrying is that Indonesia’s coal capacity additions have been outpacing clean energy additions despite its goal of peaking emissions by 2030.

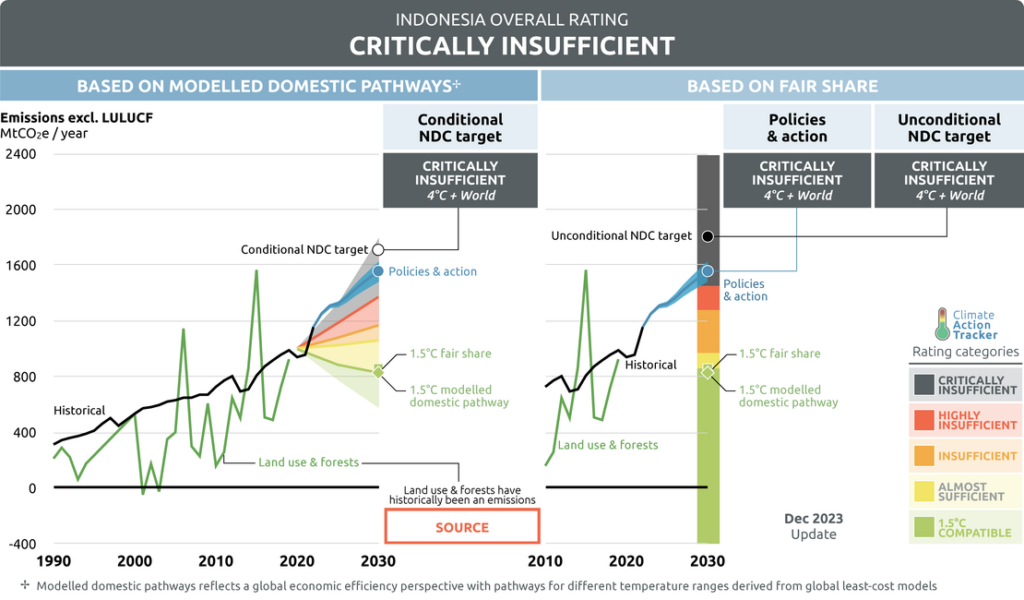

According to Climate Action Tracker (CAT), Indonesia’s huge fleet of newly operating coal plants increased the country’s emissions by 21% in 2022. Furthermore, it is likely to elevate total power sector emissions to levels more than twice those required to achieve the 1.5°C target. The country is among the worst performers in CAT’s ranking, with a “critically insufficient” rating for climate targets and policies.

Without urgent action to reduce emissions, heatwaves in Indonesia will last almost 8,000% longer by 2050. Furthermore, climate disasters threaten around 180 million Indonesians living in coastal areas.

Despite Indonesia’s vulnerability to climate change, the response is slow and stalling. The country has fallen by 10 places to 36th in the Climate Change Performance Index for 2024. The Environmental Performance Index, which assesses national efforts to improve environmental health to enhance ecosystem vitality and mitigate climate change, ranked it 164th out of 180 countries in 2022.

PLN’s coal development plans will further exacerbate those problems.

“Any new coal plant built in Indonesia is likely to operate for 35 to 40 years. By backing PLN’s coal development plans, the Asian Development Bank is helping to lock Indonesia — a country that is critical to the fight against global climate change — into a future at least partly dependent on the dirtiest of fossil fuels. The consequences of this decision, which will make it difficult for Indonesia to meet its Paris Agreement emissions targets, are global. But they will be felt most acutely by the people of Banten,” said Novita Indri, energy campaigner at Trend Asia.

The ADB Can Still Salvage the Situation

Indonesia is at a watershed moment, with billions of dollars in climate financing to start flowing in upcoming years under the JETP. The ADB and other financiers have a significant responsibility to ensure that the funding will accelerate Indonesia’s decarbonisation journey rather than worsen the environmental and health crisis caused by coal plants. The authors of the Smog and Mirrors report also urge the ADB to remedy the impacts of its past coal funding, including its support for earlier development and expansion of the Suralaya Power Station in the 1980s and 1990s.

“The global battle against climate change will be won or lost in Asia and the Pacific,” said ADB President Asakawa in December 2023. During the ADB’s 2024 general meeting in Tbilisi, Georgia, at the beginning of May, he once again acknowledged the threat of climate change to Asia’s development and population.

“The bank can’t claim to be helping Indonesia when their investments are destroying the environment,” says environmental campaigner Mad.

While it is true that so far the ADB hasn’t ensured that its actions fully align with their statements, it has the power to launch a much-needed change. A crucial first step is ensuring adequate and strictly imposed restrictions to prevent the misuse of the funds, avoid the massive reputational risks associated with continued fossil financing and most importantly, give Indonesians a hope in the future.

The ADB has significant influence in advocating for affected communities’ demands to be met and making sure that stories like those of Sutrisno, Mulyadi and the thousands affected in the Banten Province would be a part of the region’s history, not its future.

Viktor Tachev

Writer, Bulgaria

Viktor is a writer that specialises in green finance and ESG investment practices. He holds a Master's degree in financial markets and has over a decade of experience working with companies in the finance industry, along with international organisations and NGOs. Viktor is a regular contributor to several publications and comments on the likes of sustainability and renewable energy.

Viktor is a writer that specialises in green finance and ESG investment practices. He holds a Master's degree in financial markets and has over a decade of experience working with companies in the finance industry, along with international organisations and NGOs. Viktor is a regular contributor to several publications and comments on the likes of sustainability and renewable energy.