Environmental economics helps explain why climate change is harmful not just to the environment, but also to jobs, prices, government budgets and long-term growth. The IPCC’s latest assessment shows that economic damage from climate change is being detected in climate-exposed sectors like agriculture, fisheries and labour productivity. A recent NBER paper says “1°C warming reduces world GDP by over 20% in the long run.”

At the same time, disaster losses keep rising. Natural hazard-related disasters in 2024 alone caused about USD 242 billion in economic damage and affected more than 160 million people.

When you add up these impacts year after year, climate change clearly shows up as an economic problem.

What Is Environmental Economics?

Environmental economics studies how economic systems and environmental health interact, and how policy can align the two. In simple terms, it looks at how to allocate resources efficiently once we acknowledge that nature is not free or infinite.

“Environmental externalities” are a key concept. These are the uncompensated environmental effects of production, consumption and associated pollution that change people’s well-being or company costs but sit outside the market mechanism and are not reflected in prices. Impacts like waste production, air pollution and climate change are all forms of environmental externalities.

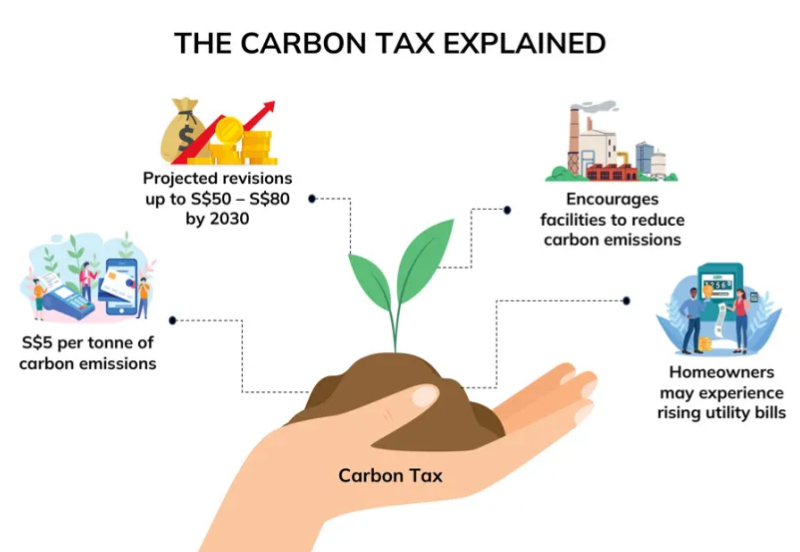

Climate policy tries to “internalise” these externalities so that they are no longer free. Carbon pricing systems are a prime example of this. For instance, Singapore introduced Southeast Asia’s first economy-wide carbon tax in 2019 at SGD 5 (USD 3.86) per tonne of CO₂e emitted. The carbon price will steadily increase to a target range of SGD 50-80 per tonne CO₂e by 2030. This approach puts a price on the externality cost of carbon and steers emitters towards lower-carbon choices.

From Neoclassical Economics Models to Fairer Outcomes

Traditional economic models often assume gradual, limited climate damage. However, studies paint a much darker picture. Climate change will cut global income by about 19% by 2049, equivalent to roughly USD 38 trillion a year, even with moderate emissions cuts. Extrapolated further, climate change could reduce average global GDP per capita by nearly a quarter by 2100.

Environmental economics serves to address this discrepancy and grapple with these nonlinear, high-damage futures. That means moving beyond textbook cost-benefit curves toward questions of risk, inequality and who can absorb the losses.

How Climate Change Is Damaging Economies Today

Extreme weather is already a significant line item on the global balance sheet. An analysis for the International Chamber of Commerce estimates that nearly 4,000 climate-related extreme weather events between 2014 and 2023 caused about USD 2 trillion in economic losses. The same study finds that just 2022 and 2023 accounted for USD 451 billion in damage.

Asia sits at the centre of this story. In 2023, Asia was again the world’s most disaster-prone region, with floods and storms causing the highest number of casualties and economic losses. Japan alone suffered around USD 90.8 billion in climate-related disaster losses between 2014 and 2023, behind only the United States, China and India. When ports flood, roads wash out or power plants go offline, global supply chains feel the shock.

Hidden Costs: Health and Labour

Beyond headline disasters, slow-burning impacts are eroding both health and incomes. In Bangladesh, extreme heat already costs up to USD 1.78 billion a year, and it forced workers to skip 250 million workdays in 2024 alone. Heat is also deadly. There were an average of 546,000 heat-related deaths per year globally between 2012 and 2021, with mortality up 23% since the 1990s.

Air pollution is another environmental externality. In Malaysia, it causes about 32,000 premature deaths a year, and in Indonesia, it reduces life expectancy by around two years. Globally, the combined effects of ambient and household air pollution are linked to 6.7 million premature deaths annually. These impacts are a significant drag on the workforce and economy.

Long-term Risks to Growth

Looking forward, climate change becomes an ever-bigger drag on growth. As mentioned earlier, projections show a 19% hit to global income by mid-century on current policy paths, with losses of up to 60% by 2100 in worst-case scenarios.

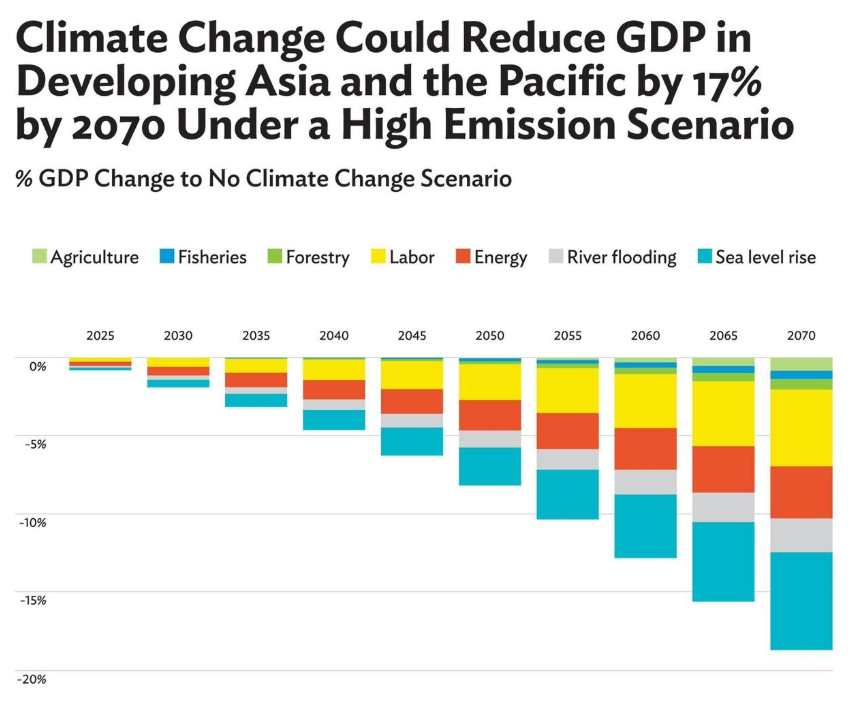

Nowhere is this clearer than in Asia. The Asian Development Bank warns that under a high-emissions scenario, climate change could shrink developing Asia and the Pacific’s GDP by 17% by 2070 and as much as 41% by 2100.

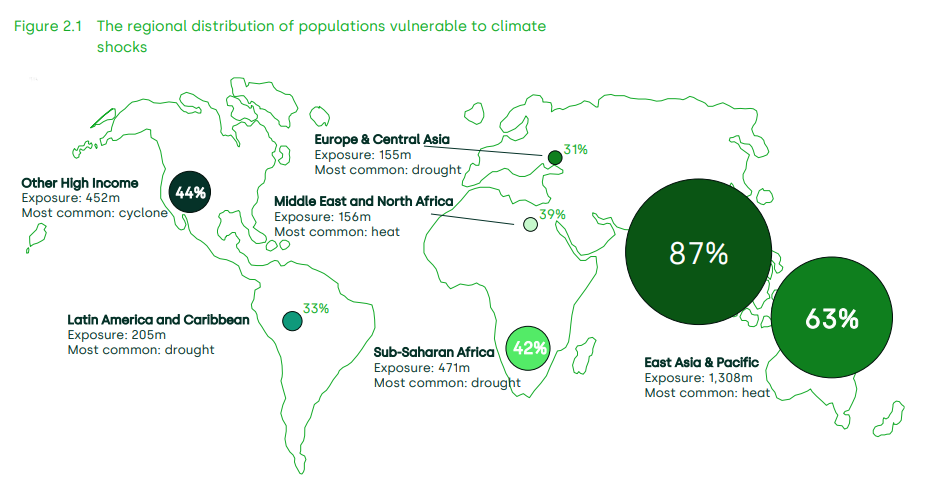

Climate-vulnerable countries across the region face especially steep projected losses because they combine high exposure to heat, floods and sea-level rise with large, often lower-income populations.

Those numbers transform climate change from a distant environmental concern into a central macroeconomic risk for finance ministries and central banks.

Who Bears the Costs of Climate Externalities?

The risks associated with climate impacts fall disproportionately on those in poverty. The largest share of people in extreme poverty live in highly climate-vulnerable regions and they have the least capacity to adapt to the changes. While many argue that funding should go to the developing world to assist climate adaptation in these regions, funding has been slow to materialise.

Even more concerning, estimates show that without assistance, climate change will push 132 million more people into extreme poverty by 2030, with the majority of those in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. This trajectory will continue to push the most vulnerable populations into high-risk environments and further put a drag on the economy.

Bangladesh’s Country Climate and Development Report shows how these overlapping risks play out. Climate change could create 13.3 million internal climate migrants in the country by 2050. At the same time, severe flooding could cut GDP by 9% annually. With these issues, Bangladesh may struggle to address its people’s needs, and its economy could falter.

Why Fair Climate Finance Matters

The economic case for fair climate finance is therefore not charity, but risk management. The Asian Development Bank estimates that developing Asia needs between USD 102 and 431 billion a year for climate adaptation. This is compared with only about USD 34 billion currently mobilised. Most of this funding is needed for flood defences, resilient infrastructure and systems that protect low-income communities.

For environmental economists, that gap is an example of underinvestment in public goods. For people on the ground, it is the difference between rebuilding after each disaster and being pushed into permanent uncertainty.

Turning Evidence Into Decisions

Environmental economics shows what people across Asia are already feeling. Climate change is bad because it quietly drains productivity, destroys assets, deepens poverty and locks in lower growth for decades to come.

The data now leaves little doubt that the costs of inaction far exceed the investments needed to cut emissions and build resilience. The sooner these economic realities shape decisions, the more space that Asia and the world will have to protect both its people and growth.

Eric Koons

Writer, United States

Eric is a passionate environmental advocate that believes renewable energy is a key piece in meeting the world’s growing energy demands. He received an environmental science degree from the University of California and has worked to promote environmentally and socially sustainable practices since. Eric has worked with leading environmental organisations, such as World Resources Institute and Hitachi ABB Power Grids.

Eric is a passionate environmental advocate that believes renewable energy is a key piece in meeting the world’s growing energy demands. He received an environmental science degree from the University of California and has worked to promote environmentally and socially sustainable practices since. Eric has worked with leading environmental organisations, such as World Resources Institute and Hitachi ABB Power Grids.