Bangladesh, one of the most pronounced climate-vulnerable nations, is ravaged by a crisis it did little to create. As sea level rises, river erosion and seasons shift unpredictably, agriculture and fisheries—the lifeblood of rural livelihoods—are devastated. Yet, while the impacts multiply, global climate finance commitments trickle in slowly, if at all.

The fingerprints of climate change are everywhere. Higher temperatures, erratic rainfall, flooding, and salinity intrusion reduce agricultural yields and render fertile land barren. Ocean warming and acidification are not only pushing fish species to extinction or forcing them to migrate but are also welcoming invasive, sometimes hostile species into coastal waters. Cyclones and storms are intensifying, reducing fishing days during peak seasons. As a result, farmers and fishermen earn less, work harder, and watch their families go hungry.

I have seen this tragedy unfold from my experience in the rural southern tip of Bangladesh, Chattagram. Several rivers in the Southern Chattogram, swollen by rising waters from the Bay of Bengal, have consumed acres of farmland and even entire homes, forcing families to flee ancestral lands and start over with nothing. This story is repeated across the country, where some 850,000 households and 250,000 hectares of arable land have already been lost. The World Bank warns that without meaningful intervention, Bangladesh could lose a third of its agricultural GDP by 2050.

But these economic shocks are only the beginning. Livelihood loss leads to displacement, forcing people into overcrowded urban slums and food insecurity. Supply shortages, inflated food prices, and falling diet quality contribute to rising malnutrition rates. Women and children are the hardest hit, often pulling out of school and sacrificing meals to keep the family going. Climate change is no longer just an environmental issue—it is a social and economic crisis, bleeding into every layer of national life.

The Urgent Need for Climate Finance

To tackle the unprecedented consequences of climate impacts, Bangladesh urgently needs climate finance—real, meaningful, and sustained. The country requires $26 billion annually to implement government mitigation and adaptation plans, yet it spends only about $2.8 billion (Bangladesh Climate Finance Landscape, 2024). This leaves a staggering $23.2 billion climate finance gap, or roughly 6% of our GDP. The private sector’s needs remain largely unmapped, and its contributions are modest.

While Bangladesh grapples with this challenge, the much-hyped global climate finance architecture continues to disappoint. The new Fund for Responding to Loss and Damage (FRLD), agreed upon at COP27, has so far proven toothless. Though countries have pledged contributions—Australia and Austria among them—the pace is glacial. With the United States backing away from the Paris Agreement again, future commitments are even more uncertain.

Challenges in Accessing Climate Finance

The mechanisms to access Global Climate Funds are still underdeveloped for Bangladesh. The country lacks a standardised and internationally accepted framework to assess and value climate-related losses, particularly non-economic ones like displacement, cultural loss, and mental trauma. Without this, we cannot even apply for the funds meant to help us. Building such frameworks will take years, and time is a luxury we no longer have.

Equally troubling is the absence of a coordinated national approach. Government responses to climate finance often appear project-based and fragmented. This must change. I propose immediately forming a high-level national working group on Loss and Damage, housed within the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEFCC) and staffed with cross-sector experts. This group should spearhead the development of valuation methodologies, policy recommendations and a long-term financing strategy.

Meanwhile, the political winds in the developed world are turning cold. Aid budgets are shrinking. The UK, Netherlands, France, and others are slashing development assistance. The US has signalled cuts of $60 billion in global development funding, according to 2025 estimates by McKinsey and Company. The COP29 trend is shifting from “new and additional” public finance toward private-sector-led “blended finance,” which may further indebted poor countries already struggling under climate pressure. This will likely expose developing and poor countries to a double-edged vulnerability, one arising from climate change and the other from increased debt.

The bureaucracy involved in accessing global funds adds insult to injury. Bangladesh has waited over five years for one of its Green Climate Fund (GCF) proposals to be approved. These delays render funds useless when they arrive as crises deepen and costs rise. If these processes aren’t streamlined significantly and immediately, the promise of climate finance will remain hollow.

Way Forward

First, every national development plan—whether the Delta Plan 2100 or the National Adaptation Plan—must include a concrete financing strategy. Vague aspirations cannot substitute for fiscal realism. Second, the government must develop a national climate finance strategy, one that aggressively explores and leverages domestic sources like private capital markets, impact investors, and green bonds.

We should also centralise climate finance mobilisation under a “climate bank” model that pools resources from international and domestic sources. This institution would ensure transparent, strategic allocation of funds across ministries, NGOs, and the private sector while tracking disbursement and impact.

On the international front, Bangladesh must overhaul how it prepares for climate negotiations. Currently, efforts start only months before COP summits, leaving little time for research, strategy, or consensus-building. I propose a permanent COP wing within the MoEFCC, supported by year-round working groups dedicated to the key negotiation streams: adaptation, mitigation, finance, technology, and capacity-building. These groups should include subject-matter experts, ensure proper documentation, and preserve institutional memory to strengthen long-term negotiation capacity.

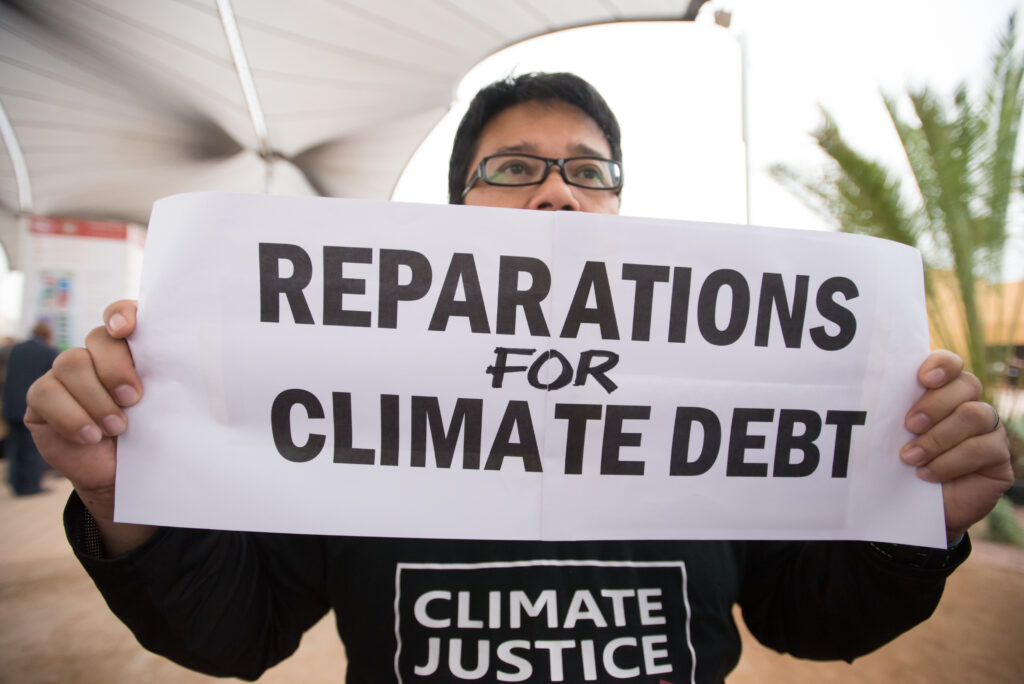

Ultimately, climate finance is not charity. It is a matter of justice. Countries like Bangladesh did not cause the climate crisis, but we are paying its highest price. The least the world’s major polluters can do is keep their promises—to provide timely, adequate and accessible finance, especially for loss and damage. Failing to do so would be morally indefensible and geopolitically short-sighted. A climate-displaced, destabilised region benefits no one.

Bangladesh’s time to act is now—strategically, systematically, and uncompromisingly. We cannot afford another year of empty pledges and delayed funding. We must build the systems, train the people, and demand the justice we deserve.

Dr. Suborna Barua is a professor at the University of Dhaka, Department of International Business. He holds blended experience of teaching courses in economics and finance at both local and foreign universities, delivering professional training on climate finance, disaster risk financing, financial modelling, financial markets, financial management, and project management, and working on cross-border research projects funded by institutions such as the World Bank, UNDP, DFID, ADB, and Oxfam International. He is the academic editor of PLOS Climate and a member of the Technical Committee for International Climate Finance Proposal Evaluation at the Ministry of Finance, Government of Bangladesh.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Climate Impacts Tracker Asia