In 2023, climate science institute Climate Analytics asked: “Can we wait until 2025 for greenhouse gas emissions to peak?” In journalism, Betteridge’s law of headlines states that the answer to headlines ending in a question mark can usually be answered with “No.” The case with Climate Analytics’ question was no exception. Yet, here we are in 2025 — not only have global emissions failed to peak, but they continue to hit record highs.

The consequences are concerning. According to the latest attribution study by scientists from World Weather Attribution (WWA), Climate Central and the Red Cross Climate Centre, human-caused climate change brought an additional month of extreme heat for 4 billion people worldwide in 2024.

“This is not a surprise or an accident,” the authors note. The climate crisis is intensifying extreme heat — making such events longer-lasting, more frequent and more dangerous for billions.

However, the science on extreme heat is unequivocal: its drivers, impacts, and solutions are well known. In that sense, addressing the problem is no longer a question of understanding but one of will.

Human-Caused Climate Change Brought an Average of 30 Days of Extreme Heat to 4 Billion People in 2024, report says

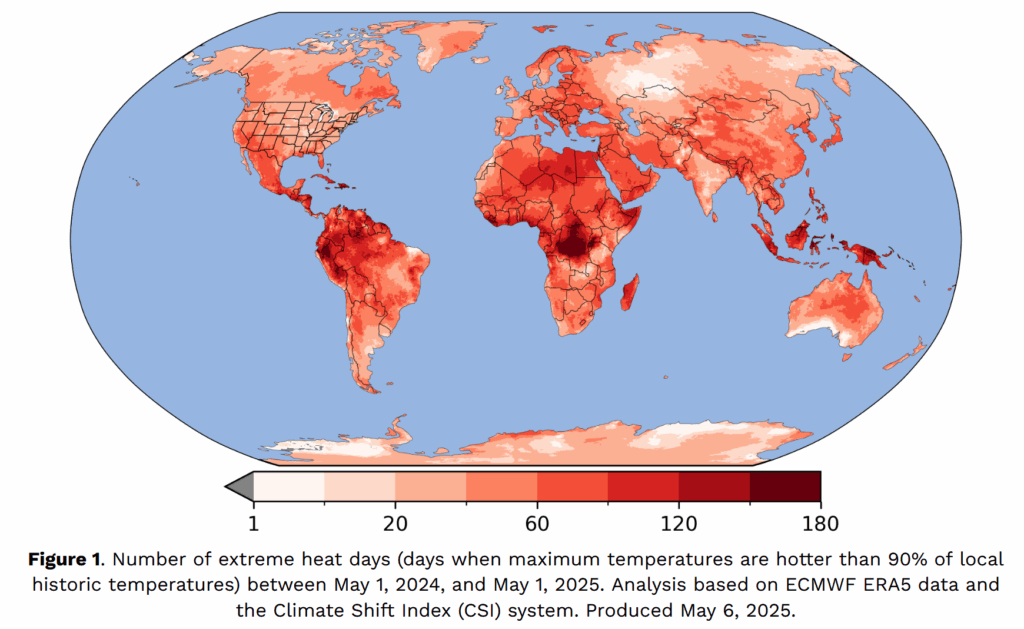

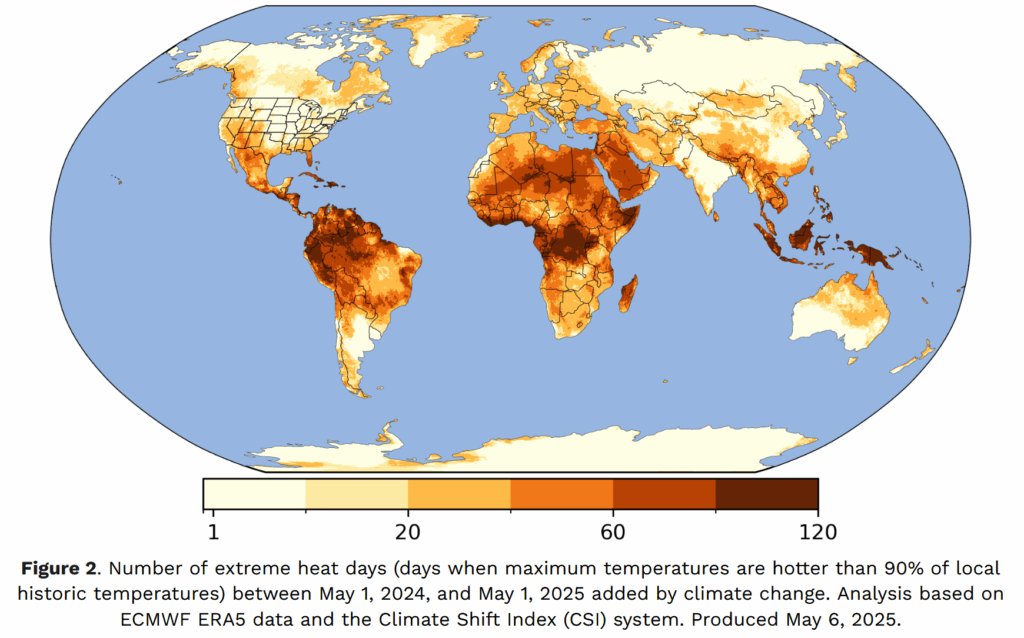

The report published ahead of June 2, global Heat Action Day, revealed that man-made climate change added at least an entire month of extreme heat for half of the world population in the past year. The group of scientists behind the research found that throughout 2024, climate change at least doubled the number of extreme heat days in over 195 countries and territories. Scientists define “extreme heat” as temperatures hotter than 90% of historical observations in a particular area compared to a world without climate change.

“This study needs to be taken as another stark warning,” said Dr. Friederike Otto, co-lead of WWA and senior lecturer in climate science at Imperial College London.

The study, which analyses data from May 2024 to May 2025, identified 67 events in 232 countries classified as “extreme heat events”. Climate change made all of them more likely.

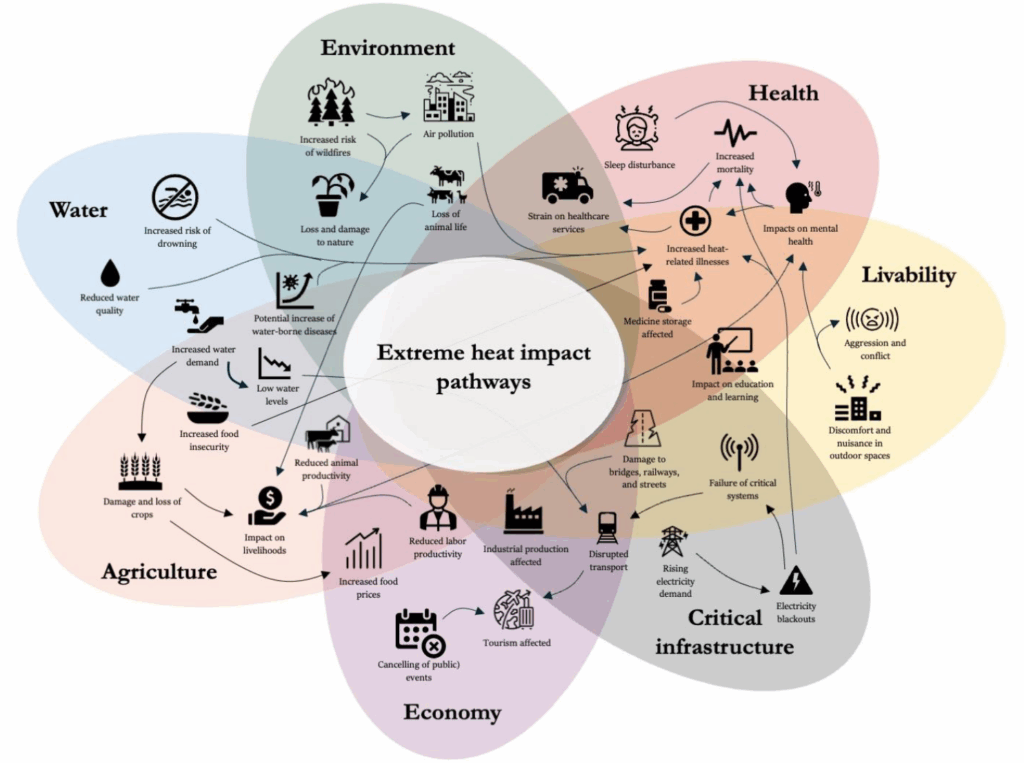

“These frequent, intense spells of hot temperatures are associated with a huge range of impacts, including heat illness, deaths, pressure on health systems, crop losses, lowered productivity and transport disruptions,” explains Dr. Mariam Zachariah, WWA researcher at the Centre for Environmental Policy, Imperial College London.

Through their work, the scientists aim to raise awareness of heatwaves, particularly recognising and responding to heat exhaustion and heat stroke, which are proving deadly for an increasing number of people every year worldwide.

“There is no place on Earth untouched by climate change — and heat is its most deadly consequence,” said Dr. Kristina Dahl, vice president for science at Climate Central.

However, Asian countries were again among the most affected. The Philippines, for example, experienced 106 days of extreme heat. Without human-induced climate change, the average person in the country would have experienced only 26 such days. Indonesians suffered 105 days of extreme heat, with 99 of them attributed to man-made global warming. For Vietnam, the result was 69 days of extreme heat that would have been just 14 without climate change.

The Extreme Heat Waves of 2024 Are a Peek Into the Future

The past 10 years (2015-2024) were the 10 warmest years on record, according to the World Meteorological Organization. Throughout 2024, temperatures were 1.55°C above pre-industrial levels, while experts say the world will permanently breach 1.5°C within the next five years. The UN forecasts that current emissions reduction pledges put the planet on track for a temperature increase of 2.6°C- 3.1°C this century.

The world’s top climate scientists aren’t optimistic either. After surveying scientists from the IPCC last year, The Guardian found that 80% envision a future where temperatures are at least 2.5°C warmer, while almost half consider at least 3°C likely. Just 6% deem 1.5°C possible.

Worryingly, some scientists are concerned that the temperature changes that we are witnessing defy climate models and their predictive capabilities. For example, recent research by a team from Columbia University found mysterious hotspots suffering from repeated heatwaves worse than all existing simulations on every continent except Antarctica. The body of evidence that actual daily temperature records are increasingly outpacing model predictions is also growing, with recent temperature extremes remaining hard to explain, even by NASA.

The Risks of Extreme Heat Remain Underreported and Underestimated

Despite all the red flags and continuous warnings, the joint study of the World Weather Attribution, Climate Central and the Red Cross Climate Centre notes that the extreme heat threat remains underreported in many countries, particularly low- and middle-income nations.

Heat Related Illnesses and Deaths

The primary reason is that the impact of extreme heat on human health and well-being isn’t well-documented. For example, scientists note that heat-related deaths are often misattributed to comorbid conditions (struggling with two or more diseases or conditions present simultaneously).

At the same time, the impacts of extreme heat are hitting the most vulnerable groups the hardest. Among them are the elderly, outdoor workers, people with pre-existing medical conditions, low-income and marginalised communities and individuals lacking proper access to medication, health care, cooling or safe housing.

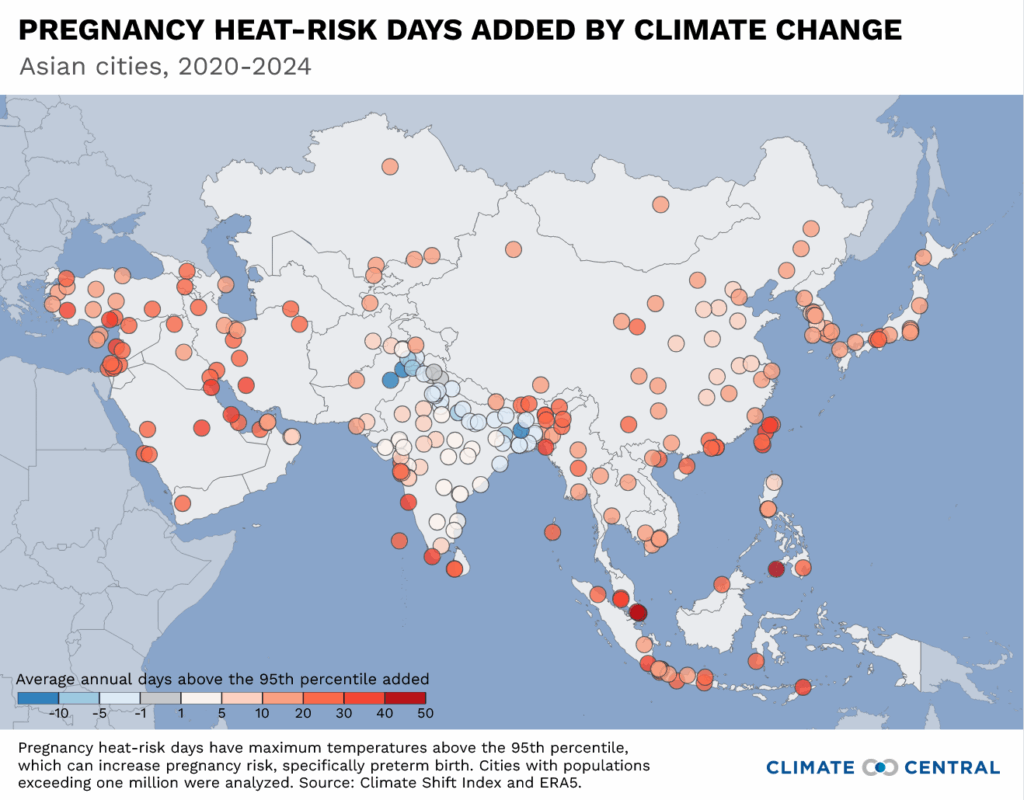

Pregnant people are also more prone to severe heat-related health impacts. A recent study by Climate Central revealed that, over the past five years, climate change has at least doubled the number of days considered dangerous for pregnant individuals in nearly 90% of countries and territories and 63% of cities. The most significant increases in pregnancy heat-risk days due to climate change occurred primarily in developing regions with limited access to health care, including the Caribbean, and parts of Central and South America, the Pacific Islands, Southeast Asia and sub-Saharan Africa.

However, the negative impact of periods of sustained extreme heat spans beyond threatening human health and well-being. It is a multidimensional threat that also strains the health sector, reduces economic output, disrupts water availability and energy infrastructure and impairs agricultural productivity. It can also compound with other extremes, such as droughts or earthquakes. It can disrupt disaster relief efforts after the devastating earthquake in Myanmar, prompting or amplifying humanitarian crises.

The fact that extreme heat events remain underreported and poorly documented negatively impacts global understanding of heat-related health and well-being risks, loss and damages. As a result, it also undermines adaptation efforts.

However, the systemic nature of the negative impacts of extreme heat necessitates a comprehensive national response that encompasses all aspects of society and all affected sectors of the economy.

Solutions Exist, But We Aren’t Using Them

The scientific consensus is that current efforts to monitor and manage heat-related risks face various barriers. One is the lack of accepted definitions for heatwaves, hindering standardised data collection and early warning system development. In regions where they exist, they are often ineffective and fragmented, with limited cooperation between relevant authorities — meteorological, health, and emergency agencies. Low public awareness of heat-related health risks and the inability of vulnerable groups to cope with periods of extreme heat due to a lack of resources or access to essential services also complicate prevention efforts.

“Through our interactions, we know that people are feeling the rise in heat, but they don’t always understand that it’s being driven by climate change, and that it will continue to get much, much worse,” explains Roop Singh, head of urban and attribution at the Red Cross Red Crescent Climate Centre.

For others, the unease stemming from climate change comes from a sense of uncertainty and the feeling that things are out of our control, and the changes are happening faster than we can adapt. However, the report not only illustrates the scale of the problem and the urgent need for adaptation and heat action but also sets out key strategies to prepare for heatwaves. These include increased reporting and monitoring of heat impacts, as well as the development of heat action plans, which are highly effective in reducing death tolls during heat waves.

“We need to quickly scale our responses to heat through better early warning systems, heat action plans and long-term planning for heat in urban areas to meet the rising challenge,” adds Singh.

The study’s authors also list strengthening emergency health services, incorporating cooling support into social protection programs and reinforcing critical infrastructure such as water, electricity and transport systems as other effective complementary strategies.

At the individual level, members across high-risk groups and affected communities can focus on adjusting strenuous activity to cooler times of day, resting frequently and staying hydrated.

Adaptive measures like these can offer short-term relief. However, alone, they will soon become increasingly insufficient to protect communities from the escalating risks. The magnitude of the problem calls for a comprehensive approach that prioritises long-term resilience through mitigation efforts, the most effective of which is phasing out fossil fuels.

“We know exactly how to stop heatwaves from getting worse: restructure our energy systems to be more efficient and based on renewables, not fossil fuels, and create more equal and resilient societies,” explains Dr. Otto.

Frontline communities don’t need a reminder that current policies are completely inadequate for staying below the Paris Agreement’s 1.5°C limit — they feel it firsthand. What they need is for their governments to ramp up climate action and submit ambitious Nationally Determined Contributions with a strong emission reduction outlook for the years up to 2035.

“Climate change is here, and it kills,” says Dr. Otto. “With every barrel of oil burned, every tonne of carbon dioxide released, and every fraction of a degree of warming, heatwaves will affect more people.”

Viktor Tachev

Writer, Bulgaria

Viktor is a writer that specialises in green finance and ESG investment practices. He holds a Master's degree in financial markets and has over a decade of experience working with companies in the finance industry, along with international organisations and NGOs. Viktor is a regular contributor to several publications and comments on the likes of sustainability and renewable energy.

Viktor is a writer that specialises in green finance and ESG investment practices. He holds a Master's degree in financial markets and has over a decade of experience working with companies in the finance industry, along with international organisations and NGOs. Viktor is a regular contributor to several publications and comments on the likes of sustainability and renewable energy.