Climate change in 2026 is expected to bring more frequent extreme weather events. After 2025 became one of the hottest years on record, bringing deadly and destructive heatwaves and monsoons, scientists warn that 2026 won’t offer the much-needed break to recover. Climate models increasingly predict that this year could prove equally or more devastating than the previous one, further highlighting the need for countries in the region to prepare in advance and protect the most vulnerable from the ever-worsening weather disasters and climate change impacts.

Preparing for Extreme Weather and the Impacts of Climate Change in 2026

After the weather extremes of 2025 wreaked havoc across the world — from record-breaking damage in the US to heatwaves and flash floods pummelling regions across Asia — scientists have identified worrying signs going into 2026.

The UK’s Met Office expects 2026 to be among the four warmest years on record, with projections indicating a 1.46°C increase above the historical average for the pre-industrial period (1850-1900). If the forecast materialises, it will make 2026 the fourth consecutive year to exceed 1.4°C in warming. Scientists from Berkley and Copernicus even warn that, if the warming El Niño weather phenomenon appears this year, 2026 could break existing temperature records.

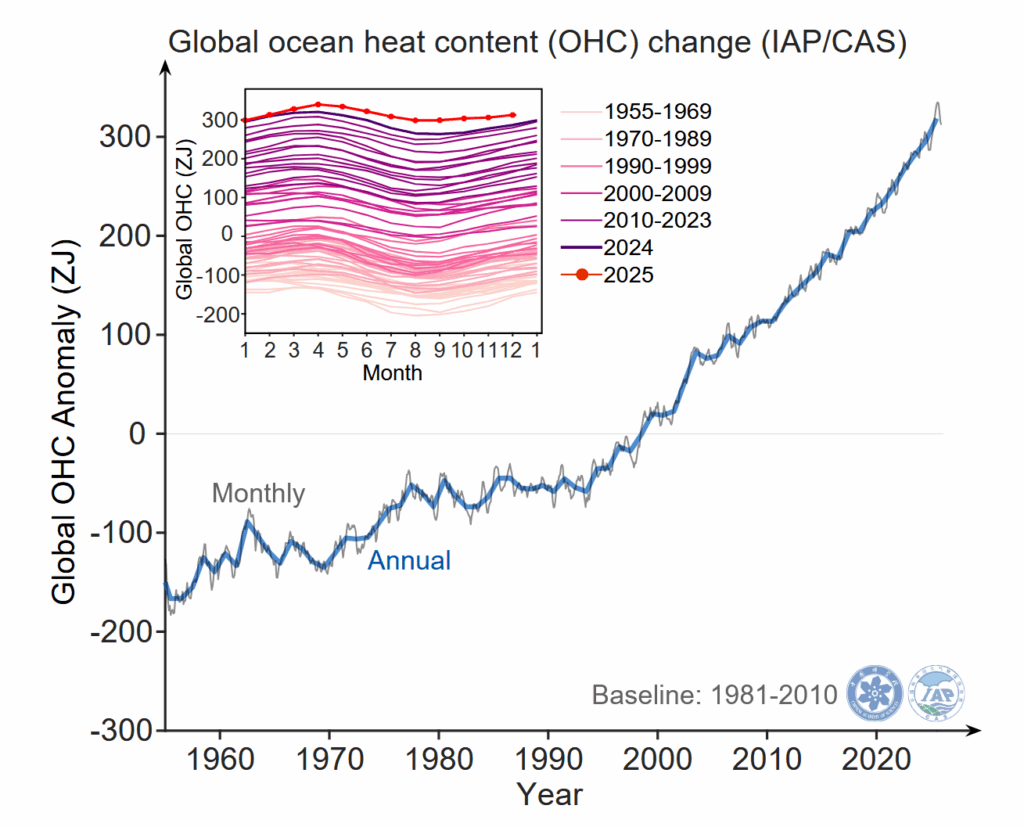

While the increase in air temperature concerns scientists, it is the rapid rise in ocean heat content that they find even more alarming. According to a recent study led by the Chinese Academy of Sciences and scientists from all over the world, the oceans, the biggest carbon sinks and one of humanity’s best weapons for taming the climate crisis, absorbed colossal amounts of heat in 2025. One of the climatologists working on the research likened it to detonating hundreds of millions of Hiroshima atomic bombs, or roughly 200 times the global electrical energy consumption in 2023.

The events continue a dangerous trajectory, with almost every year since the start of the new century setting a new ocean heat record. Since oceans absorb over 90% of the heat trapped by humanity’s carbon pollution, they are considered among the starkest indicators of the escalating climate crisis.

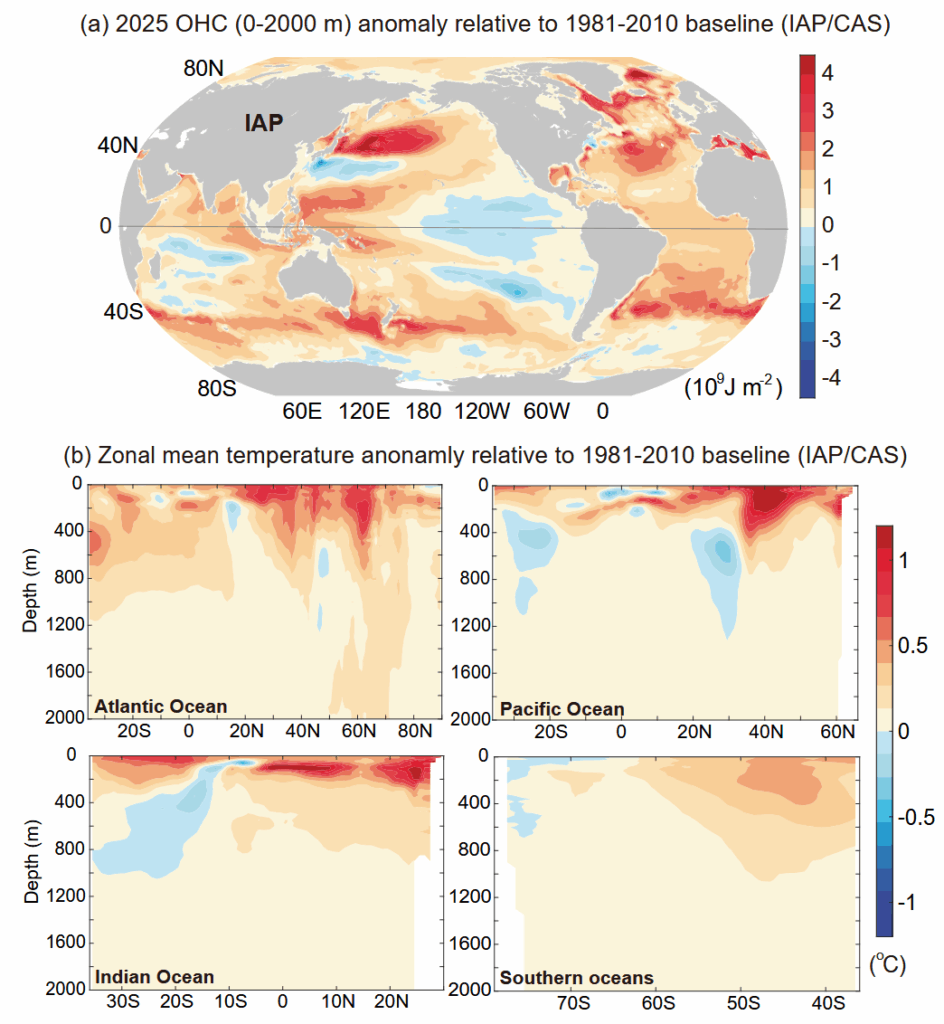

While record ocean heat and temperature anomalies have been observed worldwide, the oceans and marine areas surrounding Asia-Pacific and Southeast Asian nations have seen some of the largest extremes, the study finds.

According to scientists, oceans are now at their hottest for at least 1,000 years, heating faster than at any time in the past 2,000 years. They warn that 2025’s record heat will fuel more extreme weather in 2026, making typhoons hitting coastal communities more severe, with heavier downpours and a greater risk of flooding. Other consequences of the record ocean heat accumulation include rising sea levels that threaten billions of people in coastal areas and longer-lasting marine heatwaves that destroy marine ecosystems.

Building Resilience To Withstand the Escalating Climate Change Impacts a Key Priority for Asia

The Philippines and India have historically been among the most affected by recurring weather extremes, according to the 2026 Climate Risk Index. Between 1995 and 2024, the Philippines endured 371 extreme events, leaving 27,500 dead, 230 million affected, and causing USD 35 billion in losses. Typhoons proved the most destructive weather extremes.

Over the same period, India has repeatedly endured cyclones, floods and deadly heatwaves. In total, the country endured 430 events, leaving 80,000 dead, 1.3 billion affected and causing USD 170 billion in losses.

However, none of the Global South nations, particularly developing Asian countries, have been spared from weather extremes, especially in the past decade. Studies find that typhoons in the East and Southeast Asia have increased in their destructive power, while the number of Category 4 and 5 storms has doubled or tripled. According to data from the International Disaster Database, Central and Southeast Asian countries, including India, Pakistan, China, Indonesia, Vietnam, Thailand and the Philippines, have experienced the most floods from 2000-2022. The region had among the highest numbers of people impacted per square km. In India, extreme rainfall events have tripled since 1950.

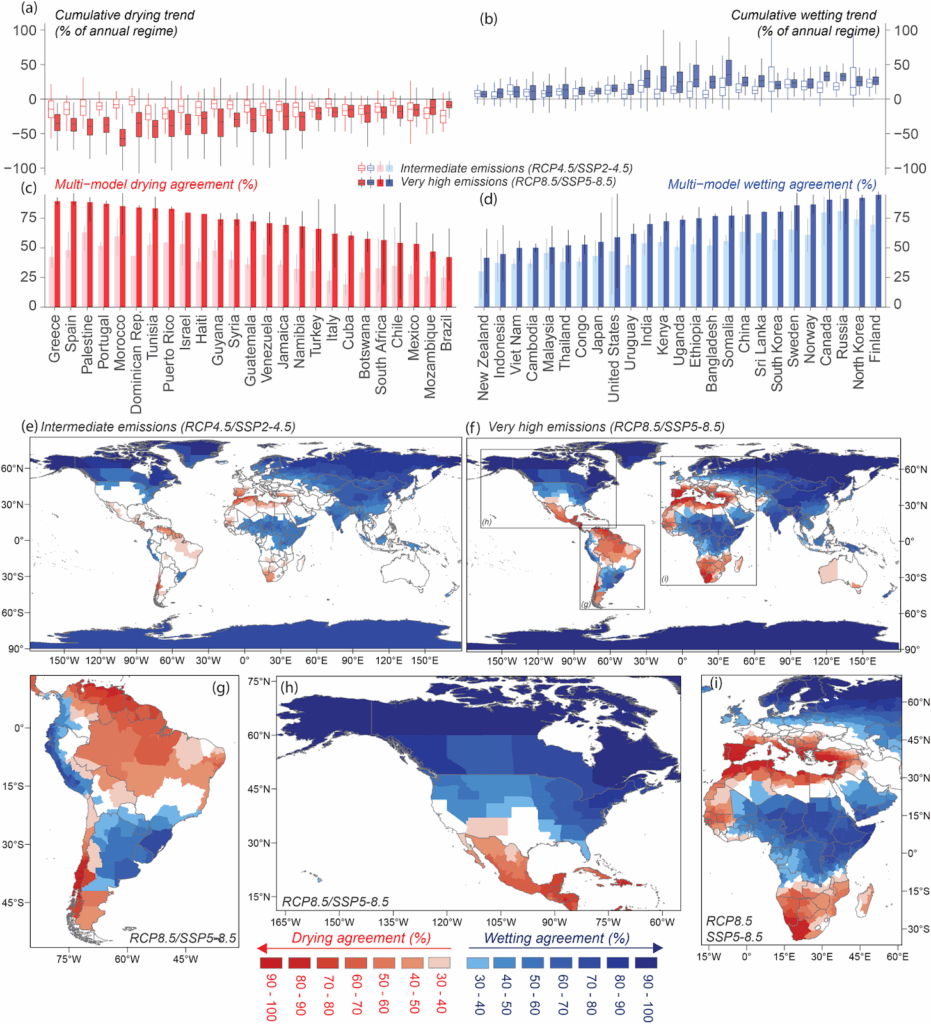

The main reason is that Asia is warming faster than the global average, with the rate nearly doubling since the 1961–1990 period. Climate models reveal that a similar worrying trend will continue charting Asia’s future. According to an analysis of 146 climate models, Asia will become significantly exposed to extreme rainfalls and flood risk by 2030. While between 3-5 billion people globally will be affected by 2100, no continent will face such substantial rainfall changes as Asia.

According to the study, of the 25 countries projected to experience increased rain patterns, 12 will be in Asia. Over 70% of the examined models show that highly populated areas, home to over 2.7 billion people in China and India, will experience increased rainfall. Other Asian countries significantly affected include Bangladesh, Japan, Thailand, Malaysia, Cambodia, Vietnam and Indonesia.

The historical evidence, as well as the projections for the future, necessitate an urgent response from governments in the region to build resilience.

Understanding the New Climate Realities and Adopting an Individual Adaptation Approach

At the regional level, governments need to adapt to new and increasingly recurring weather patterns to drive change in disaster response. Furthermore, countries will have to adopt individual measures, tailored to their specific circumstances, to protect themselves from escalating climate disasters.

For example, Indonesia, which in recent years has been ravaged by cyclones and floods following intense monsoons, will have to address the massive deforestation and landscape alteration in upland watersheds that have been taking place across different regions for decades. According to experts, these activities have largely destabilised slopes and worsened runoff during extreme rainfall and flash floods, leading to landslides and further damage to infrastructure.

After the rare cyclone Senyar swept across parts of Sumatra, causing devastating flash floods, killing at least 1,178 people and displacing around 1 million others, the government acknowledged the problem. On Dec. 23, 2025, Indonesia’s environment minister launched an investigation into eight companies operating in the affected area to assess whether their activities had contributed to the floods and landslides, ordering them to suspend operations.

Improving Infrastructure Planning and Disaster Response

A common problem across many Asian countries is the lack of proper infrastructure planning, which further exacerbates the impacts of extreme weather events, including heavy rainfall, flash floods and landslides. According to experts in urban planning, investments in infrastructure and better planning, such as giving rivers room to flow and restricting construction along riverbeds, can prove crucial.

Critical to building resilience is also preparing for high-frequency, high-intensity events in line with the new climate realities. This has proven necessary since outdated infrastructure design principles that prepare for low-intensity weather extremes are no longer capable of withstanding the consequences of the escalating climate crisis.

Faster, community-focused responses with clear local warnings, stronger coordination, urban-specific plans, protection of vulnerable groups and safer rebuilding to reduce future flood risks are also critical.

Experts advise investing in flood-control infrastructure, such as converting roadways into drainage channels, as other countries, including Japan and the US, have done. However, infrastructure should be further improved to withstand flash floods, as they are becoming increasingly frequent.

Investing in Early-warning Systems, Designing and Implementing Adaptation Plans

According to the WMO, since 2015, the number of countries reporting multi-hazard early warning systems has more than doubled. Yet 40% of countries, including some of the most climate-vulnerable nations, still lack such systems. Furthermore, according to scientists, significant gaps remain in both quality and coverage of existing early-warning systems, necessitating urgent action to close them.

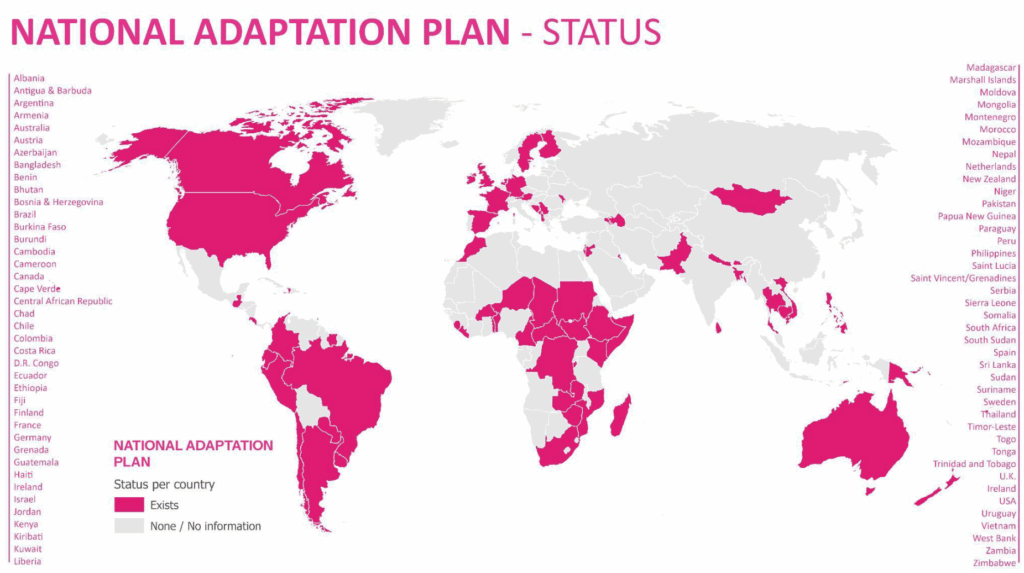

In total, the UN estimates that by 2035, the adaptation finance needs of developing countries, including many of the most vulnerable to climate change, will be at least 12 times the current international public adaptation finance flows. Furthermore, currently, many of the most climate-vulnerable nations still lack national adaptation plans.

Governments in the region should prioritise adaptation plans and early-warning systems with a long-term focus that incorporates multiple factors, including a health focus and integration into urban planning, labour protection, infrastructure and social policy. The plans should cover the entire population, specifically targeting and reaching the most vulnerable individuals, including frontline communities and low-income groups, and addressing maternal, newborn and child health risks.

Such measures will allow countries to act proactively and be prepared when the next disaster strikes, ultimately minimising damage in advance and ensuring a timely, more efficient response to protect the most vulnerable.

Tackling the Problem at Its Core Remains the Most Critical Step

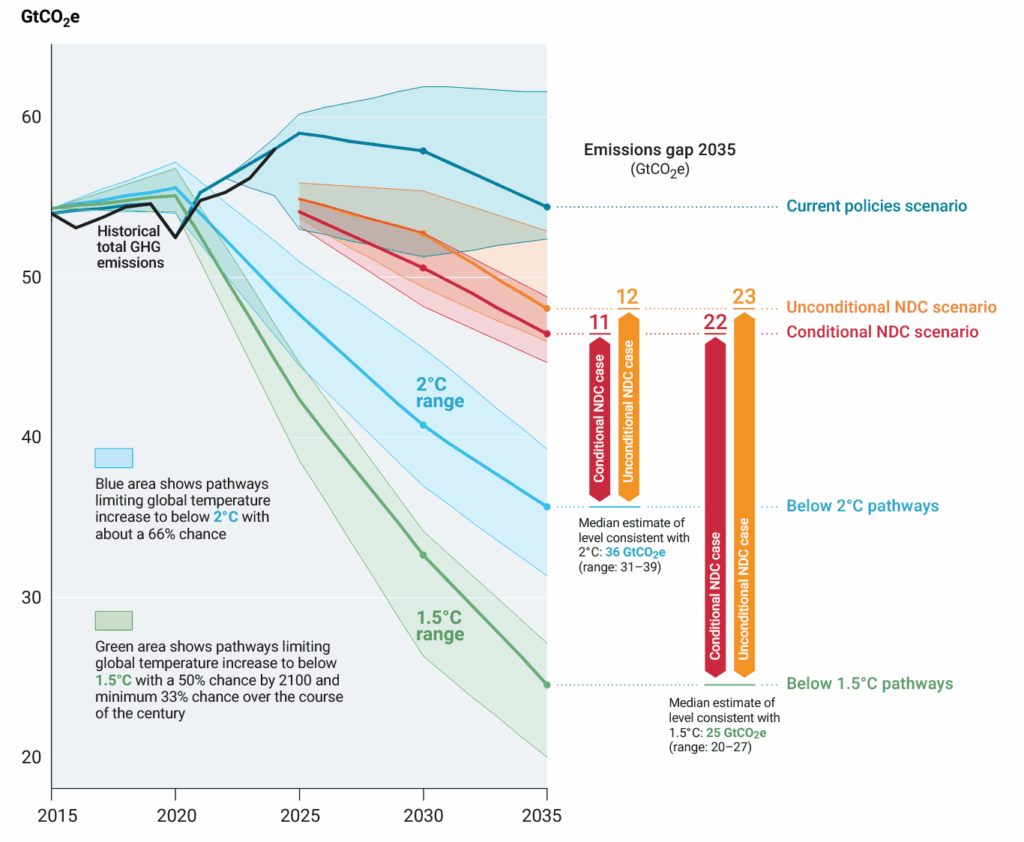

As the UN’s latest Emissions Gap Report shows, the new NDCs have limited effect on narrowing the emissions gap by 2030 and 2035, leaving the world on a dangerous global warming trajectory, well above the Paris Agreement’s temperature goal.

In that sense, preparing for extreme weather events would become progressively more expensive, challenging and inefficient if governments don’t address the root of the problem by accelerating the global clean energy transition, phasing out fossil fuels and scaling up climate action.

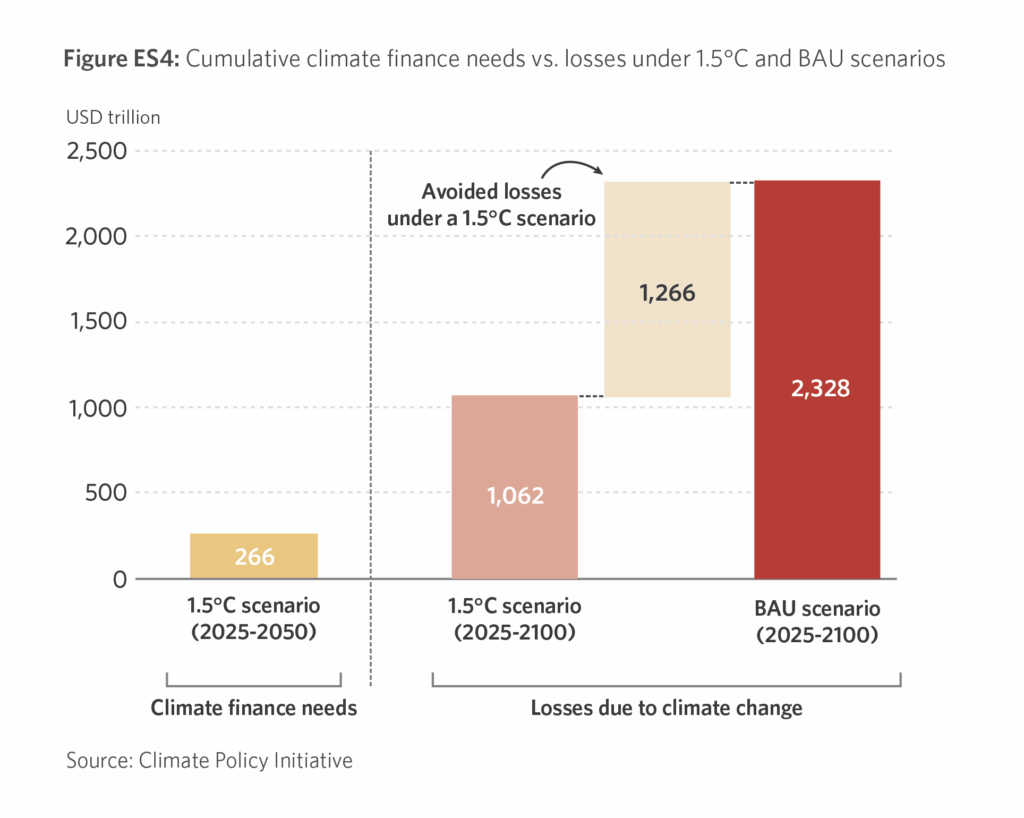

Experts and scientists warn that the cost of action is far lower than the cost of inaction. For example, the Climate Policy Institute estimates that climate finance needed to preserve the 1.5°C target ranges from USD 5.4 trillion to USD 11.7 trillion per year until 2030, and from USD 9.3 trillion to USD 12.2 trillion per year over the following two decades. For reference, the social and economic costs under a business-as-usual warming scenario are at least USD 1,266 trillion and will only worsen the longer action is delayed.

“We urgently need a rapid and sustained transition away from oil, gas and coal. Developed countries that have caused most of the warming need to take the lead and move much faster,” said Dr. Joyce Kimutai, researcher at the Centre for Environmental Policy, Imperial College London, upon the release of a report tracking the state of climate change ten years after the Paris Agreement.

However, given the dangerously high levels of “locked-in” emissions, the scientist warns that these steps alone won’t be sufficient.

“We also need to triple our adaptation efforts to protect lives and livelihoods.”

Viktor Tachev

Writer, Bulgaria

Viktor is a writer that specialises in green finance and ESG investment practices. He holds a Master's degree in financial markets and has over a decade of experience working with companies in the finance industry, along with international organisations and NGOs. Viktor is a regular contributor to several publications and comments on the likes of sustainability and renewable energy.

Viktor is a writer that specialises in green finance and ESG investment practices. He holds a Master's degree in financial markets and has over a decade of experience working with companies in the finance industry, along with international organisations and NGOs. Viktor is a regular contributor to several publications and comments on the likes of sustainability and renewable energy.