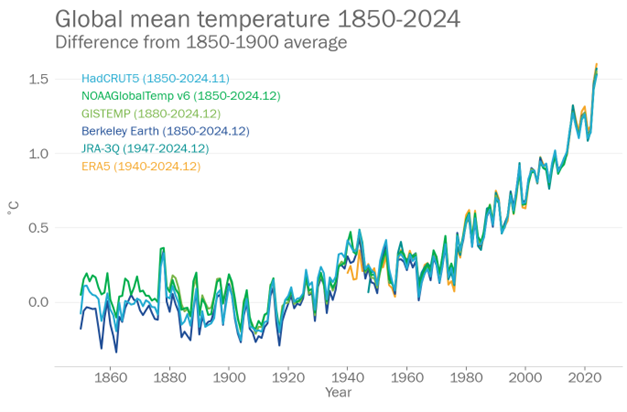

Climate anxiety is mainstream. It is a rational response to living through the hottest years ever recorded, with extreme weather reshaping daily life across the world. In 2024, the global average temperature reached about 1.55°C above the 1850–1900 average, making it the warmest year on record and the first calendar year above 1.5°C in most major datasets.

CITA’s own reporting shows what that means in practice. Between 2022 and 2023, more than 99% of humanity experienced above-average heat, and 5.7 billion people experienced at least 30 days of above-average global temperatures.

In this context, climate anxiety is less a personal problem than a natural response to a hotter, more unstable world.

What Is Climate Anxiety?

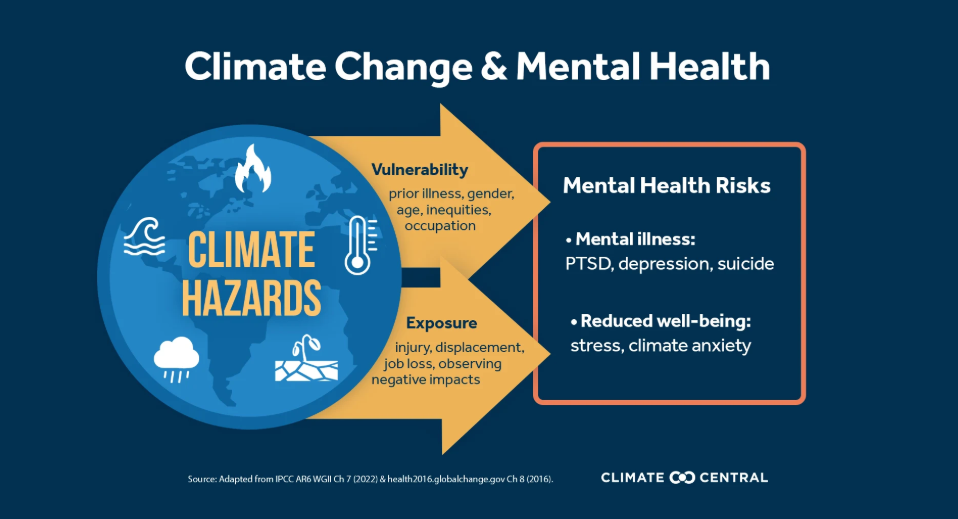

Researchers use “climate anxiety” or “eco anxiety” for feelings of persistent worry, grief or fear specifically about climate change and its impacts. The World Health Organization describes climate change as a serious threat to mental well-being and a “risk amplifier,” as it disrupts livelihoods, housing, food security and social support systems that keep people well.

Eco-Grief – A Chronic Fear of Environmental Doom

Climate anxiety or eco-grief is not a formal diagnosis, but a pattern of emotions and symptoms. These cover a broad spectrum, from disturbed sleep and racing thoughts to depression, anger and a sense of powerlessness when people feel the problem is huge and the response to combat climate change is slow.

Importantly, feeling climate anxiety does not mean someone is irrational. It’s not a mental illness. It often reflects an accurate reading of risk and a strong sense of responsibility for others. The problem is less the emotion itself and more whether people have support, agency and credible plans to act.

How Common Is Climate Anxiety or Eco-Anxiety Among Young Adults?

The most detailed data on climate anxiety still comes from young people. A 2021 study surveyed 10,000 people aged 16 to 25 across 10 countries and found that 59% were very or extremely worried about climate change, and 84% were at least moderately worried. More than half reported feeling sad, anxious, angry, powerless or guilty, and 45% said climate anxiety affected their daily life and functioning.

Newer work suggests these concerns have only deepened. A 2024 study of adults in the United States found that 85% were at least moderately worried and nearly 58% very or extremely worried about climate change, with strong links between worry, climate distress and plans for action.

Although most of these surveys primarily focus on Europe and North America, there is growing evidence from Asia that young people and communities living with climate impacts are experiencing similar or stronger levels of distress.

How Climate Change Is Shaping Mental Health in Asia

Living Through Heatwaves, Floods and Storms – Impacts of Global Warming

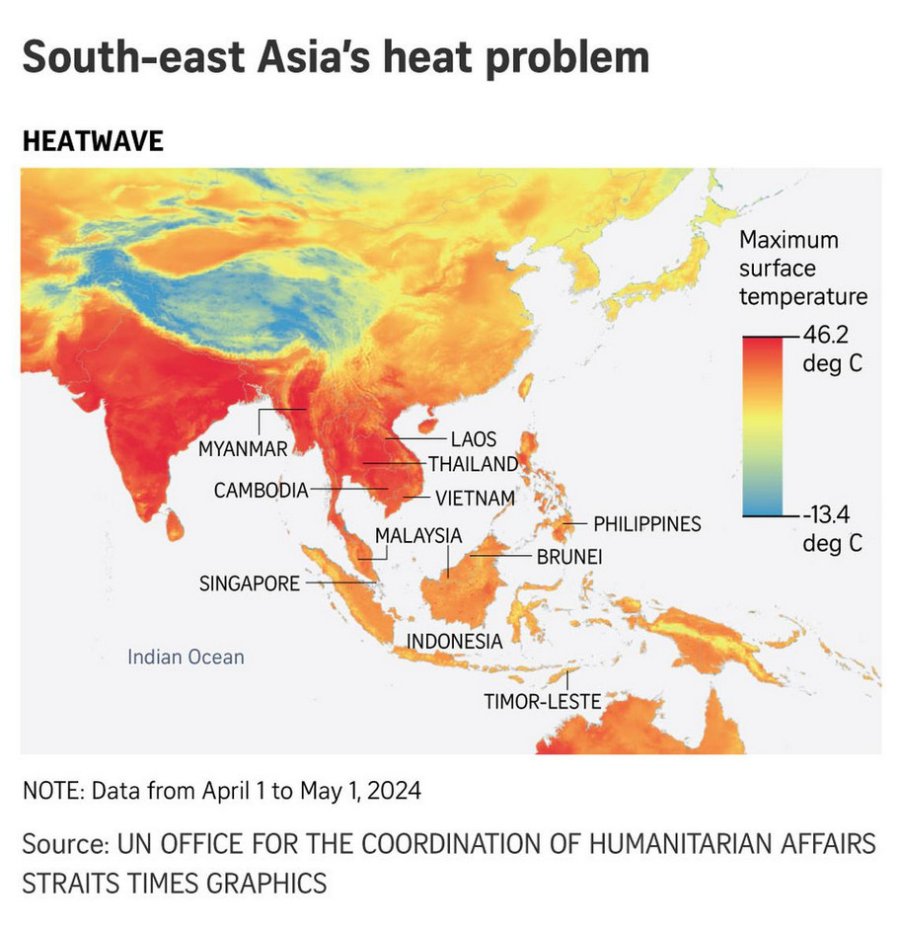

Across Asia, climate anxiety is grounded in lived experience. The State of the Climate in Asia 2024 report confirms that the region is warming nearly twice as fast as the global average, with rising temperatures driving more intense heatwaves, heavy rain, floods and tropical cyclones.

For example, the 2024 and 2025 heatwaves in South and Southeast Asia saw record-shattering temperatures that forced school closures, triggered health warnings and stretched power grids from India and Bangladesh to Thailand and the Philippines.

Each natural disaster brings a spike in trauma, anxiety and grief. For many people, especially those already facing poverty or displacement, there is little time to recover before the next event hits.

Slow-burning Stress for Farmers, Workers and Urban Residents

There is also a slow-burning layer of stress. Data from South and Southeast Asia shows significant links between extreme weather events and higher rates of depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress in the region, especially among low-income communities.

Furthermore, a 2023 review in Lancet Planetary Health shows that higher outdoor temperatures are associated with worse mental health outcomes, especially during heatwaves. For farmers facing repeated crop failures, outdoor workers who can no longer safely work in the middle of the day, or urban residents trapped in overheated housing, climate change creates financial strain and uncertainty about the future.

Why Climate Change Anxiety Matters

Climate anxiety has clear implications for organisations and governments. When large numbers of employees, students or community members are struggling with climate anxiety on top of direct impacts like heat stress or flood damage, it becomes a workplace and systems issue rather than an individual failing.

For employers in Asia, this intersects directly with workforce risk. For example, around half of India’s GDP depends on work that is exposed to dangerous heat, from construction and agriculture to street vending and logistics. When heat makes outdoor work unsafe and workers worry about their health, homes and families, the stress does not stay at the job site. It travels into households, classrooms and community spaces.

From a systems perspective, climate anxiety is a warning sign that climate impacts and institutional responses are out of sync. The WHO has urged countries to integrate mental health into climate planning, arguing that failing to do so will deepen inequalities and erode trust in public institutions.

Signals That Decision-makers Can’t Ignore

Climate anxiety also carries a political message. A recent study found not only high levels of worry but also strong feelings of betrayal and abandonment toward governments seen as failing to protect young people. These people across regions report that climate concerns shape decisions about education, work, where to live and whether to have children.

From Climate Anxiety to Climate Action

The goal is not to eliminate climate anxiety, but to manage it and channel it into constructive action. Staying informed through reliable sources while setting limits on social media helps keep concerns grounded in facts rather than rumours. At the same time, taking meaningful action, from joining local adaptation efforts to pushing for stronger climate policy at the school, work or city level, can restore a sense of agency.

For government and companies, climate anxiety is useful data. It points to where people feel unprotected and unheard. Using extreme weather data as a base, leaders can identify hotspots where physical risk and social vulnerability overlap, then target support there. Just as important is creating real participation channels so stakeholders can help shape these responses.

Climate anxiety is rising because the risks themselves are increasing. It is a reminder that current climate action is not yet keeping people safe. Leaders who listen to that signal and respond with credible plans that protect both mental health and livelihoods will be better placed to guide their communities through a hotter, more uncertain future.

Eric Koons

Writer, United States

Eric is a passionate environmental advocate that believes renewable energy is a key piece in meeting the world’s growing energy demands. He received an environmental science degree from the University of California and has worked to promote environmentally and socially sustainable practices since. Eric has worked with leading environmental organisations, such as World Resources Institute and Hitachi ABB Power Grids.

Eric is a passionate environmental advocate that believes renewable energy is a key piece in meeting the world’s growing energy demands. He received an environmental science degree from the University of California and has worked to promote environmentally and socially sustainable practices since. Eric has worked with leading environmental organisations, such as World Resources Institute and Hitachi ABB Power Grids.