Examples of circular economies are seen in countries around the world. Across Asia, they are starting to change how cities handle waste and how industries think about materials. This comes at a time when the region is warming almost twice as fast as the global average and faces the most weather disasters in the world.

At the same time, the world is still mostly on a take-make-waste model. The Circularity Gap Report 2024 estimates that only about 7.2% of the global economy is circular, down from 9.1% in 2018. At the same time, humans extracted around 582 billion tonnes of materials between 2016 and 2021, almost as much as during the whole 20th century.

This pattern of consumption directly relates to rising emissions and the climate risks observed worldwide.

The Linear Economy: A Growing Waste and Climate Problem

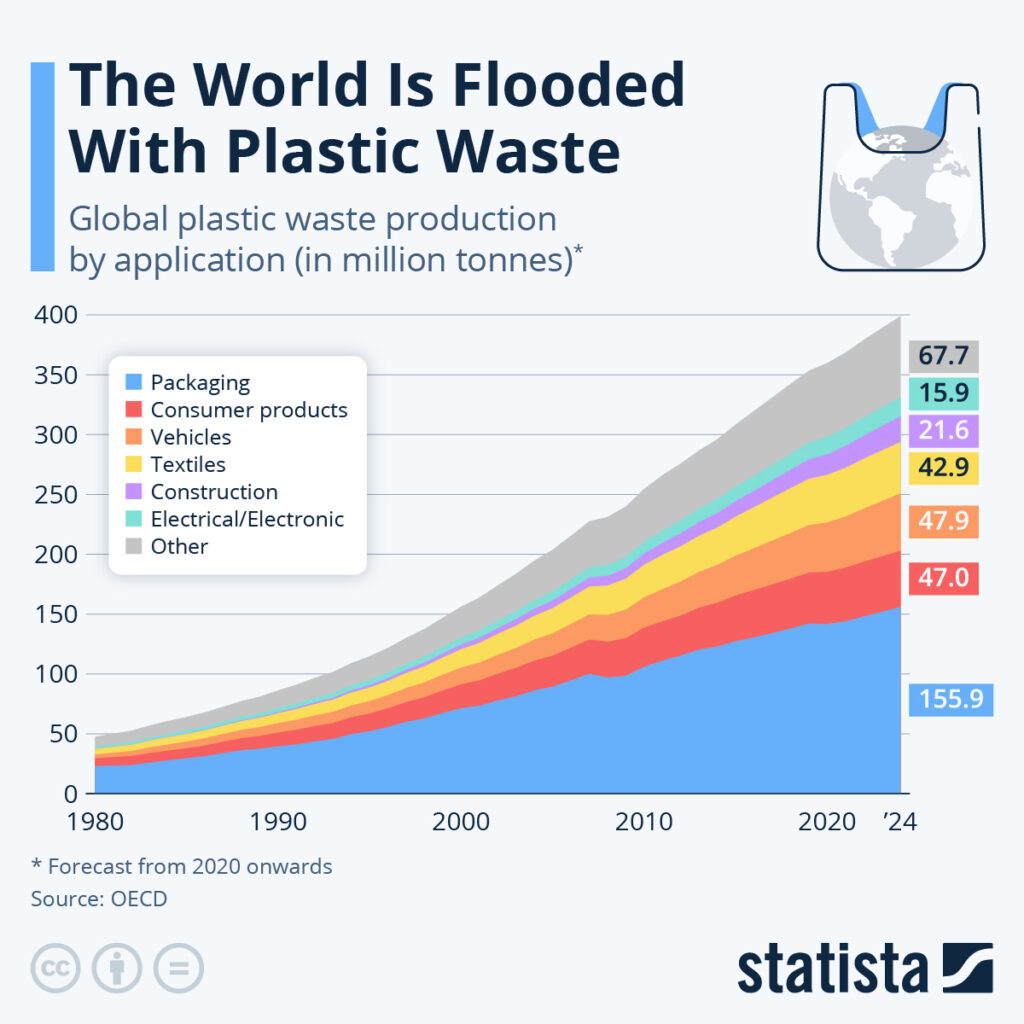

A linear economy treats nature as an endless source of inputs and a bottomless sink for waste. Municipal solid waste is already around 2.3 billion tonnes a year and, on current policies, could reach 3.8 billion tonnes by 2050. The direct financial cost of waste management is around USD 252 billion per year.

E-waste is one of the fastest-growing streams, with 62 million tonnes of discarded electronics in 2022, but only 22.3% was properly collected and recycled. This wastes an estimated USD 62 billion in recoverable materials.

Asia, as the world’s manufacturing hub, feels these pressures sharply. From plastics leaking into rivers to coal and steel locked into new buildings and infrastructure, every tonne of material that is used once and dumped drives demand for more extraction, more energy and more emissions. That is the core problem the circular economy can solve.

What Is the Circular Economy and Why Does It Matter? – Three Principles of Circular Economy

A circular economy is an economic system that aligns with three design principles: eliminating waste and pollution, circulating products and materials at their highest value and regenerating nature. It goes beyond traditional recycling, which typically addresses food waste only at the end of a product’s life. A circular approach asks different questions from the start: Can this product be designed to last longer? Can the product be repaired, shared or remanufactured so that materials rarely become waste in the first place?

In practice, this can mean reuse-and-refill systems for packaging instead of single-use plastics, remanufacturing industrial equipment instead of scrapping it, or product-as-a-service models in which companies retain ownership of materials and have strong incentives to design for durability and recovery. Recycling still matters, but it becomes just one tool in a broader system that keeps materials in productive use for as long as possible.

A Climate Solution for the ‘Other 45%’

So how does this tie into other climate targets? Most current climate plans focus on energy: cleaning up power, transport and buildings. Switching to renewable energy and improving efficiency can deal with roughly 55% of global greenhouse gas emissions. However, the remaining 45% relates to how we produce and use materials like cement, steel, plastics, aluminium and how we manage land and food.

By applying circular strategies in just those five sectors, analysis shows that the world can cut emissions by 9.3 billion tonnes of CO₂ equivalent in 2050. In total, this is roughly equal to today’s emissions from all forms of transport.

This means implementing circular economy principles is not a side project. It is a core mitigation pathway for heavy industry, fast-growing cities and food systems, which are all expanding as incomes rise.

Circular Economy Examples Already Reshaping Asia

Cities Turning Organic Waste Into Resources

Several Asian cities are now piloting circular approaches to organic waste, which often accounts for a large share of municipal waste. In Minamisanriku, a coastal town in Japan, a biomass facility known as Minamisanriku BIO takes kitchen waste and sewage sludge and uses anaerobic digestion to produce biogas. As a result, the biogas generates electricity and creates thousands of tonnes of liquid fertiliser each year. A 2024 case study found that the plant processed approximately 10,000 tonnes of targeted waste in 2020, generated approximately 66,600 kWh of electricity and produced approximately 2,150 tonnes of liquid fertiliser.

This type of system turns a disposal cost into local energy and regenerative agriculture, cuts the amount of waste entering landfills and reduces methane emissions from decomposing organic matter. Furthermore, reviews of anaerobic digestion in Asia highlight similar opportunities in China, Southeast Asia and South Asia, where food waste is abundant, and chemical fertiliser costs are rising.

Value Chains Closing the Loop in Textiles and Plastics

Textiles are another central pressure point. Global textile waste is rising quickly, and until now, traditional sorting has been a bottleneck. Research into ideas like AI-enabled textile sorting shows that solutions are on the way. Ultimately, as it becomes easier to recycle blended and mixed textile streams, it is easier for businesses and consumers to support circular fashion models.

On electronics and plastic, policy is already pushing companies toward circular economy principles. The Philippines’ Extended Producer Responsibility Act requires large companies to recover a rising share of their plastic packaging footprint. This started at 20% in 2023 and rises to 80% by 2028, with fines for noncompliance.

India’s 2022 E-waste Management Rules require companies that produce or import electronics to meet e-waste collection and recycling targets. These kinds of frameworks create a business case for reuse, repair and high-quality recycling infrastructure.

How Asia Can Scale Circular Solutions

Scaling the circular economy in Asia means moving from pilot examples to policy, finance and business models that make circular choices the default. Further, governments can set material productivity and waste reduction targets, expand extended producer responsibility (EPR) beyond plastics and e-waste and use climate or development funds to build infrastructure for organic-waste digestion, composting and high-quality recycling. Cities can embed circular projects in climate plans, integrate informal workers into safer recovery systems and favour repairable and recycled products in public procurement.

For companies, the circular economy is a way to cut input costs, manage supply risks and open new revenue from repair, remanufacturing and product-as-a-service models. Digital tools, including AI and material tracking platforms, can help map flows, match secondary materials with buyers and design products that are easier to reuse and recycle.

Circular Economy as Climate Action

The idea of a circular economy is sometimes framed as just a waste solution. However, it is actually a climate and development strategy. By redesigning products and systems so that materials circulate rather than being discarded, governments and businesses can cut emissions that are not typically addressed by switching from fossil fuels to renewable energy. Plus, it has the added benefit of reducing direct pollution and associated health impacts and creating more resilient local economies. In a warming world, doing more with what already exists is not just efficient, it is climate action.

Eric Koons

Writer, United States

Eric is a passionate environmental advocate that believes renewable energy is a key piece in meeting the world’s growing energy demands. He received an environmental science degree from the University of California and has worked to promote environmentally and socially sustainable practices since. Eric has worked with leading environmental organisations, such as World Resources Institute and Hitachi ABB Power Grids.

Eric is a passionate environmental advocate that believes renewable energy is a key piece in meeting the world’s growing energy demands. He received an environmental science degree from the University of California and has worked to promote environmentally and socially sustainable practices since. Eric has worked with leading environmental organisations, such as World Resources Institute and Hitachi ABB Power Grids.