The climate crisis is claiming the life of one person every minute worldwide, and no region is more affected than Asia, which has the highest average mortality per extreme weather event. At the same time, Asian countries face the largest gap between the scale of needed and actually delivered climate financing, ultimately impeding local adaptation efforts. Scientists warn that the challenges for frontline communities will continue escalating, necessitating not only urgent mobilisation of capital, but also its adequate delivery and use so that the most vulnerable and the least responsible for the climate crisis can better cope with it.

Weather Disasters and Escalating Climate Risks Woven Into Asia’s Past, Present and Future

According to Germanwatch’s Global Climate Risk Index 2025, four of the 10 most affected countries by climate change between 1993 and 2022 are from Asia. Myanmar suffered the highest number of fatalities. China and the Philippines had the most people affected per 100,000. India ranked sixth.

The Philippines and India, in particular, have historically been among the most affected by recurring weather extremes. Between 1995 and 2024, the former endured 371 extreme events, claiming the lives of 27,500, affecting 230 million and causing USD 35 billion in losses. Typhoons proved the most destructive weather extremes. Over the same period, cyclones, floods and deadly heat waves repeatedly struck India. In total, the country endured 430 events, leaving more than 80,000 casualties, affecting 1.3 billion people and causing USD 170 billion in losses.

Extreme Weather Events in Asia

The IPCC’s Sixth Assessment Report, the world’s most complete body of climate science, found that Asia has the highest average mortality per extreme weather event globally. Over 50% of the events have resulted from extreme heat. In fact, today, Asia is warming faster than the global average, with the rate nearly doubling since the 1961–1990 period.

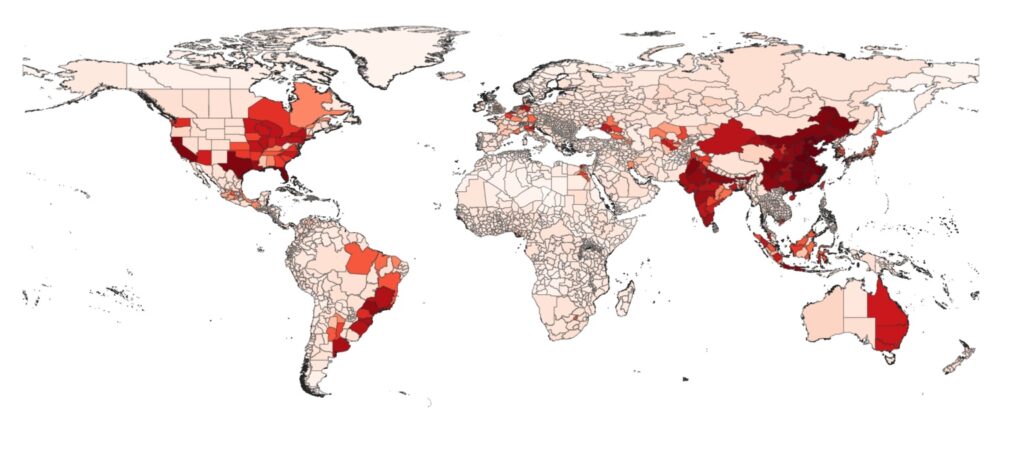

Furthermore, the World Bank warns that 70% of the most flood-exposed people (1.24 billion) today live in South and East Asia. China and India account for over a third of global exposure. In several South and East Asian regions, more than two-thirds of the population is facing significant flood risk.

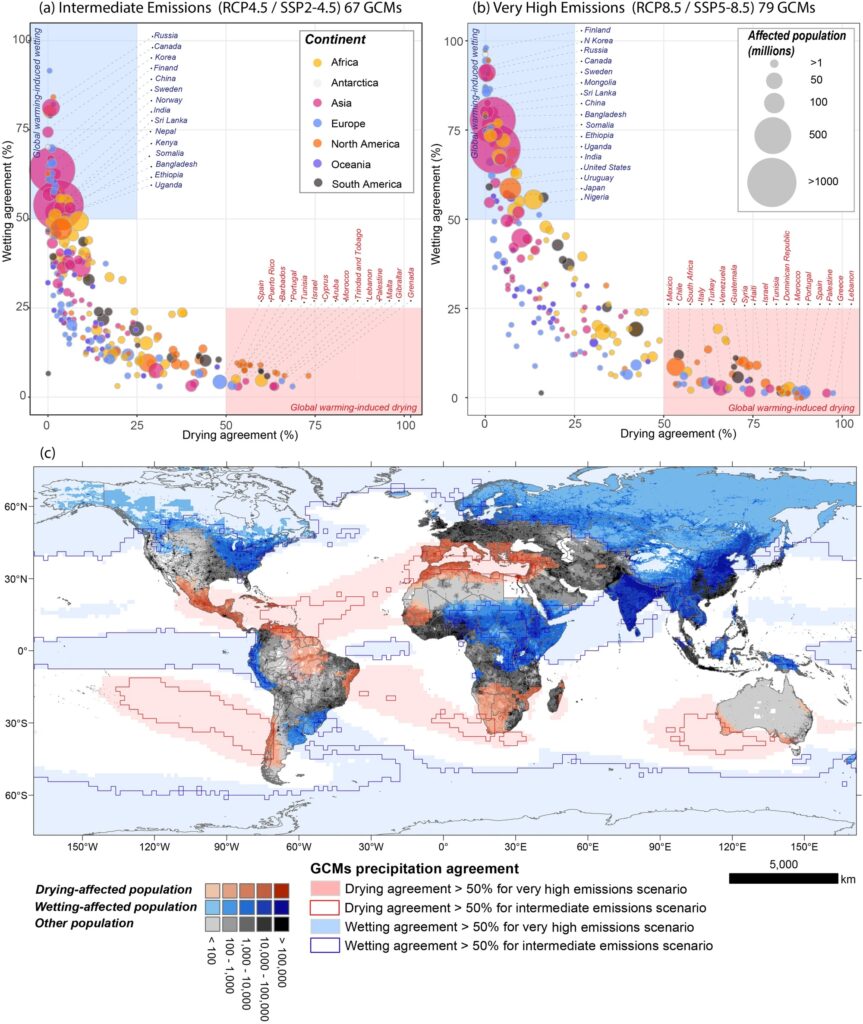

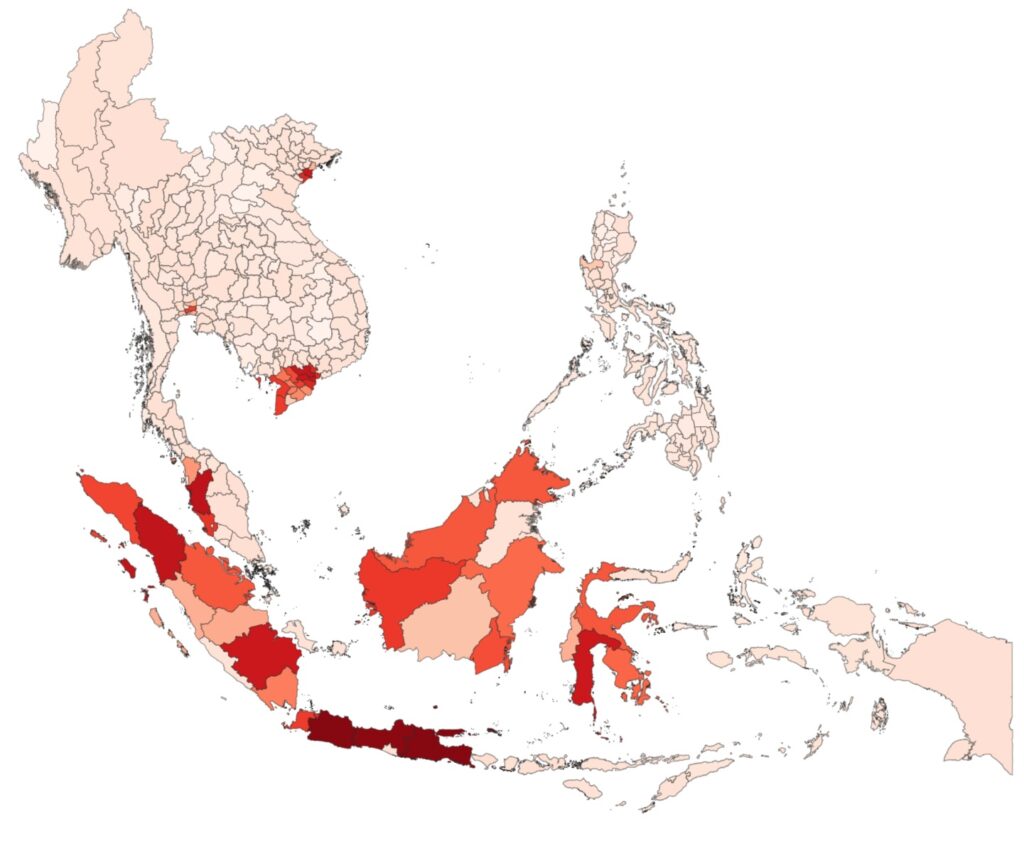

Scientists predict the situation to intensify going forward, with Asia threatened to become significantly exposed to extreme rainfalls and flood risk by 2030. Disaster-prone regions and highly populated areas across China, India, Bangladesh, Japan, Thailand, Malaysia, Cambodia, Vietnam, and Indonesia will be affected, the researchers warn.

According to the climate risk database of the Cross Dependency Initiative (XDI), 114 of the top 200 provinces facing the most serious potential damage by 2050 are in Asia. The biggest climate risk is in East and Southeast Asia, with 29 of the top 200 provinces in China, another 20 in Japan and four in South Korea. Southeast Asia, notably Vietnam and Indonesia, holds 36 of the top 200 places in the ranking.

The experts also find that East Asia and South East Asia will experience the greatest increase in average damage between 1990 and 2050 globally, driven predominantly by sea level rise and secondarily by flooding risk. The steepest escalation will occur post-2030, XDI finds.

According to scientists, as the climate crisis intensifies, the situation will worsen both in the severity and frequency of weather extremes, necessitating an urgent response from governments in the region and international partners to build resilience and improve adaptation capabilities.

UNEP: Developing Countries’ Adaptation Needs 12-14 Times the Current Climate Financing Flows

According to a 2025 analysis by DDP, titled “A Decade of National Climate Action: Stocktake and the Road Ahead,” despite the measurable progress in climate governance over the past decade, adaptation efforts remain insufficient, and climate finance falls short of the scale and pace required.

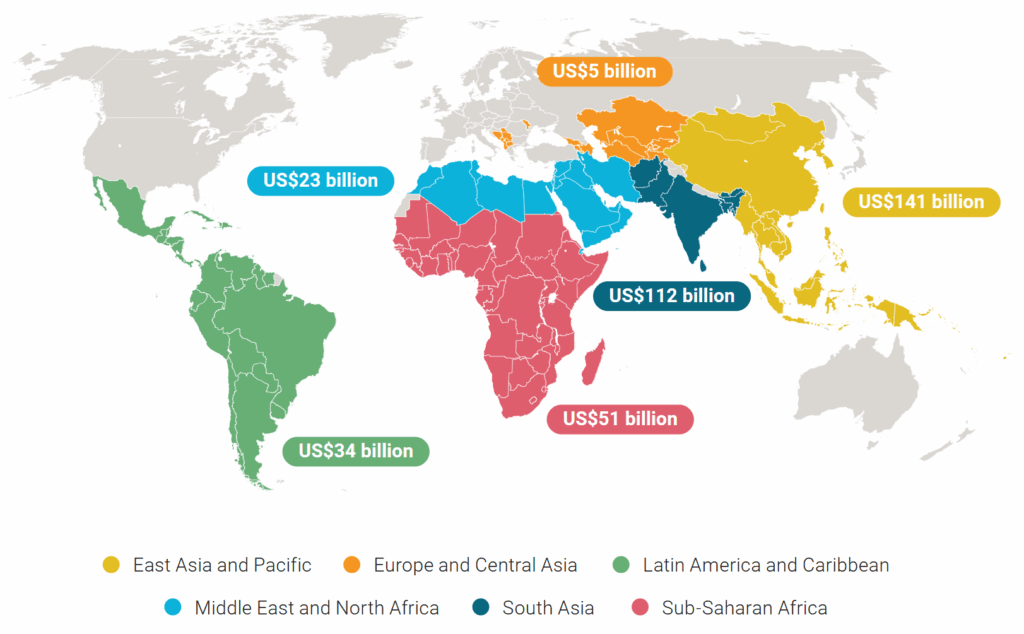

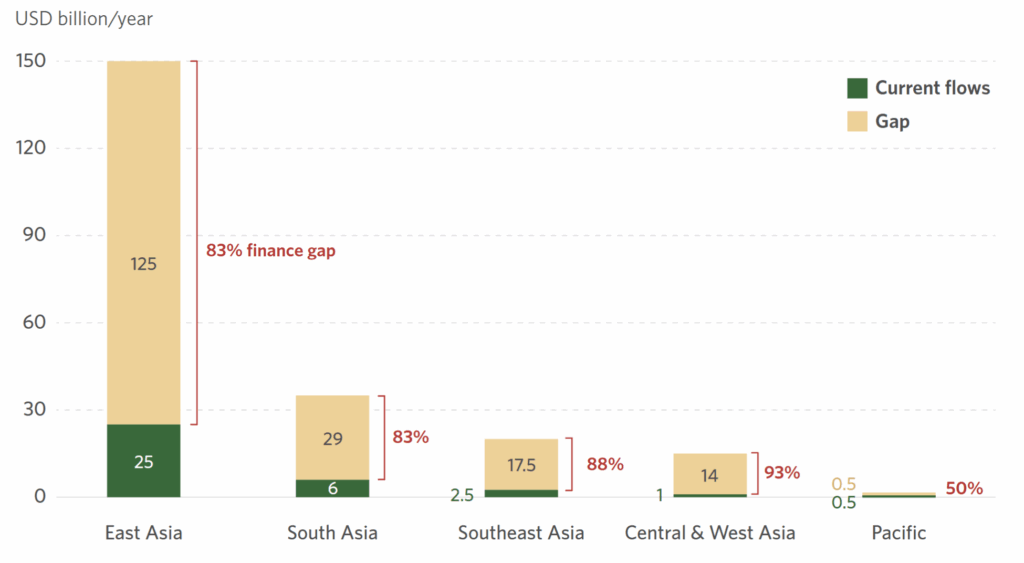

The latest report on global adaptation financing trends by the UNEP, “Adaptation Gap Report 2025: Running on Empty,” identifies a major gap between what developing countries need and what they actually receive. According to the experts, the adaptation financing needs of developing countries is between USD 310 and USD 365 billion per year in 2035. Yet, the current international public financial flows for adaptation for developing countries totalled USD 26 billion in 2023, down from USD 28 billion the previous year. The gap in adaptation financing needs in developing countries remains 12-14 times the current flows. According to the UNEP, East Asia and the Pacific remains the region with the biggest climate adaptation needs, followed by South Asia.

The Climate Policy Initiative (CPI) estimates the financing flows and gap in Central and West Asia at 93%, followed by Southeast Asia with 88% and East and South Asia, both with 83%.

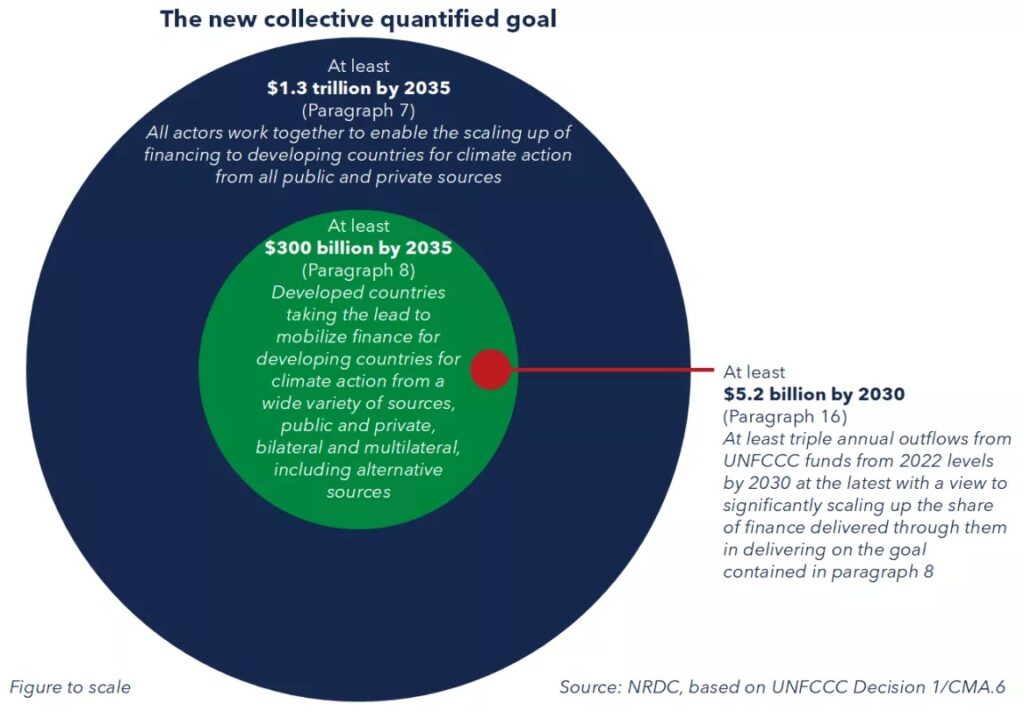

The New Collective Quantified Goal on Climate Finance, finalised at COP29, is among the most promising instruments for bridging the financing gap for developing countries. Its first goal includes mobilising at least USD 1.3 trillion per year from public and private sources by 2035. The second target aims at scaling up at least USD 300 billion per year by 2035 in the form of public finance provided by developed countries and voluntary contributors, as well as private-sector stakeholders. Experts believe that all targets under the NCQG cap are achievable with commitment and cooperation from governments, international institutions and the private sector.

Climate Change Adaptation Financing Not Just a Question of Quantity, but Quality

Experts argue that, when it comes to adaptation finance, it isn’t only about quantity, but quality as well. Alternatively, raising the needed financing is one side of the coin. But also, how it is structured, how fast it is delivered, its flexibility and its distribution are equally as important.

“The finance gap is not just a number, it’s a reflection of the growing risks to people’s health, safety, and dignity. We need urgent, scaled-up adaptation finance that prioritises grants and concessional support, not more debt,” notes Dr. Jemilah Mahmood, a professor and executive director of the Sunway Centre for Planetary Health at Sunway University in Malaysia.

For governments, international partners and public and private sector stakeholders, the UNDP has developed a dedicated adaptation finance strategy guideline that draws upon best practices. Centred around four pillars — data collection and engagement, investment prioritisation, mapping and matching financing needs and sources and operational planning and coordination, it provides a practical, country-driven framework to translate adaptation priorities into investable strategies and financial flows.

According to the Climate Policy Initiative (CPI), bridging the adaptation gap in Asia also requires enhancing local participation and leadership to ensure that the provided financing supports community-led adaptation projects and reaches those who need it the most. The experts note that local communities, institutions and organisations that suffer the harshest climate impacts currently receive a disproportionately small share of adaptation finance in Asia, yet remain the most engaged and innovative in identifying context-specific and sustainable adaptation solutions. Furthermore, the analysts highlight the importance of improved integration of local and indigenous knowledge.

The CPI also advises that countries in Asia, especially small and frontier economies, should be supported in accessing international capital markets and obtaining financing from global climate funds. The experts identify capacity constraints, complex and resource-intensive application procedures and lengthy project approval processes among the leading challenges preventing governments in the region from timely accessing adaptation funds.

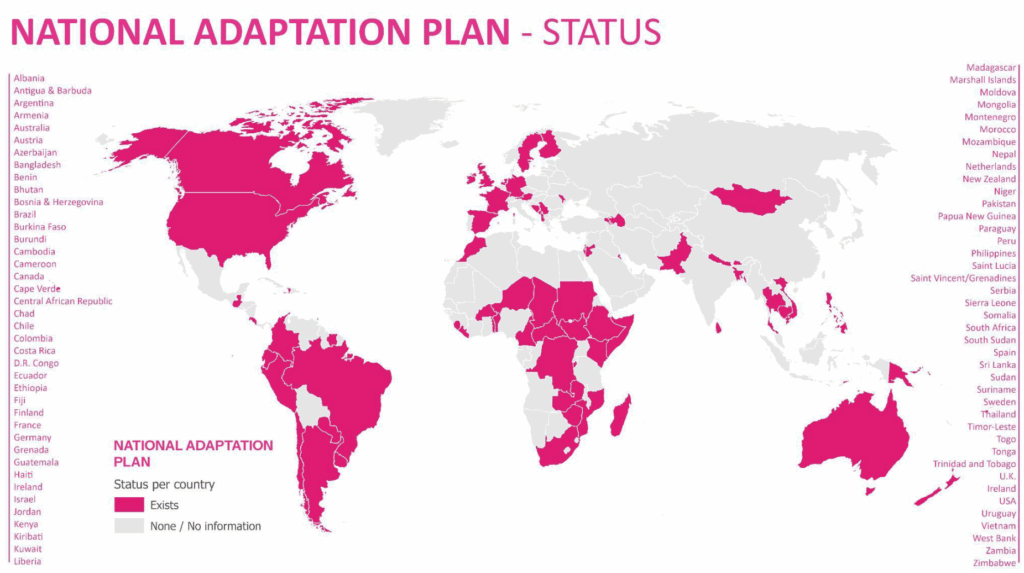

However, governments of developing countries in the region also have a lot of work to do, including improving capacity and coordination and introducing adequate policy frameworks for planning and spending climate adaptation funds.

For example, they have to understand the new climate realities that Asian countries have to deal with and prepare for the increasing risk of recurring weather disasters. Improving infrastructure planning and disaster response are other necessary measures, as are prioritising the design of national adaptation plans and the deployment of early warning systems, which 40% of nations, including some of the most climate-vulnerable, still lack.

The Cost of Inaction Far Exceeds the Cost of Action

Asia faces the perfect storm: the region is the most vulnerable to climate change and suffers the highest mortality per extreme weather event. Furthermore, many Asian countries also grapple with challenges like poverty, food and water insecurity, refugee displacement and unplanned urbanisation. These further exacerbate the problem.

At the same time, the region faces the biggest gap in climate adaptation financing.

“Cutting emissions alone won’t be enough. We also need to triple our adaptation efforts to protect lives and livelihoods,” says Dr. Joyce Kimutai, researcher at the Centre for Environmental Policy at Imperial College London.

The tools for doing so are available and well understood. It is now in the hands of developed nations to scale up financial support to the needed levels, including from both public and private sector stakeholders, and deliver it to developing countries, mainly in the form of grants. Governments of developing Asian countries have an equally important role, including introducing ambitious domestic reforms and ensuring that adaptation financing is delivered timely and where it is needed the most, ultimately helping to protect the most vulnerable and least responsible for the climate crisis.

Viktor Tachev

Writer, Bulgaria

Viktor is a writer that specialises in green finance and ESG investment practices. He holds a Master's degree in financial markets and has over a decade of experience working with companies in the finance industry, along with international organisations and NGOs. Viktor is a regular contributor to several publications and comments on the likes of sustainability and renewable energy.

Viktor is a writer that specialises in green finance and ESG investment practices. He holds a Master's degree in financial markets and has over a decade of experience working with companies in the finance industry, along with international organisations and NGOs. Viktor is a regular contributor to several publications and comments on the likes of sustainability and renewable energy.