The Maldives are sinking. It sounds dramatic, but it reflects a real and measurable risk. The Maldives is the lowest-lying country in the world, and even small increases in sea level can have serious consequences.

The key question is not whether the Maldives is suddenly collapsing into the ocean, but how fast the sea level is rising around the islands, how that rise interacts with reefs and coastlines and what it means for people living there.

Why the Maldives Is So Exposed to Rising Seas

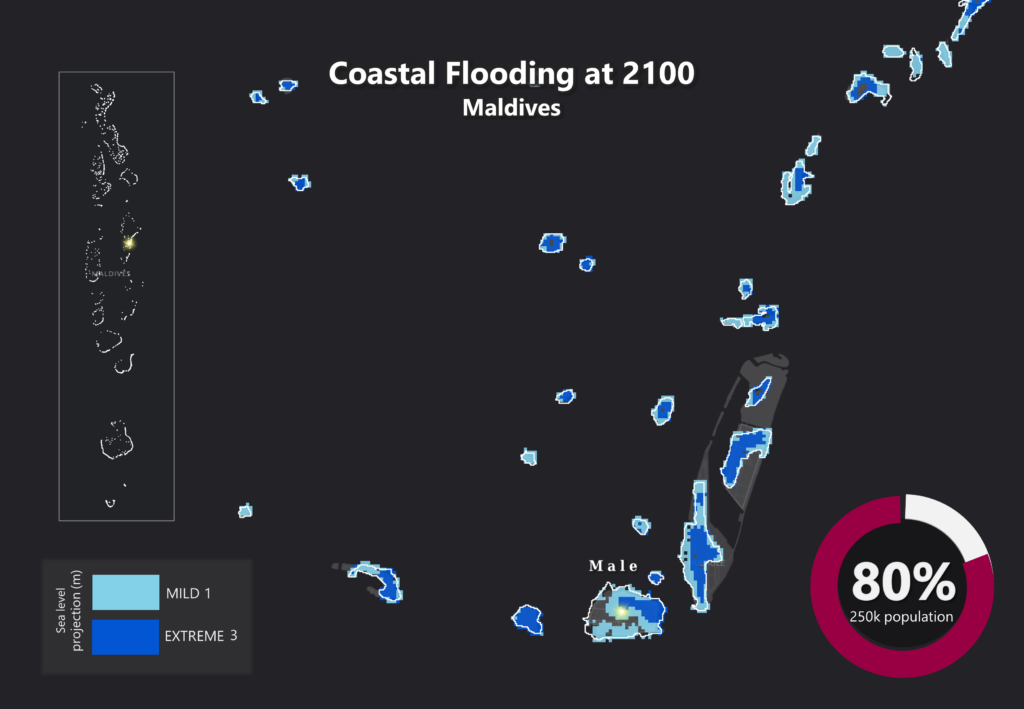

The Maldives’ exposure to sea-level rise begins with its geography. The country is made up of about 1,200 coral islands spread across 26 atolls, with no interior high ground. According to the World Bank, the average elevation is around 1.5 m above sea level. Plus, roughly 80% of the land area lies less than 1 meter above sea level. This leaves a minimal buffer between daily tides and the built environment.

The distribution of people and infrastructure also shapes exposure. More than 45% of homes are located within 100 m of the coast, and critical assets such as ports, airports, power infrastructure, roads and desalination plants are almost entirely coastal. Tourism, the backbone of the Maldivian economy, is similarly tied to beaches and nearshore areas. This concentration means that even modest sea-level rise can translate into widespread economic and social disruption.

Are the Maldives Sinking?

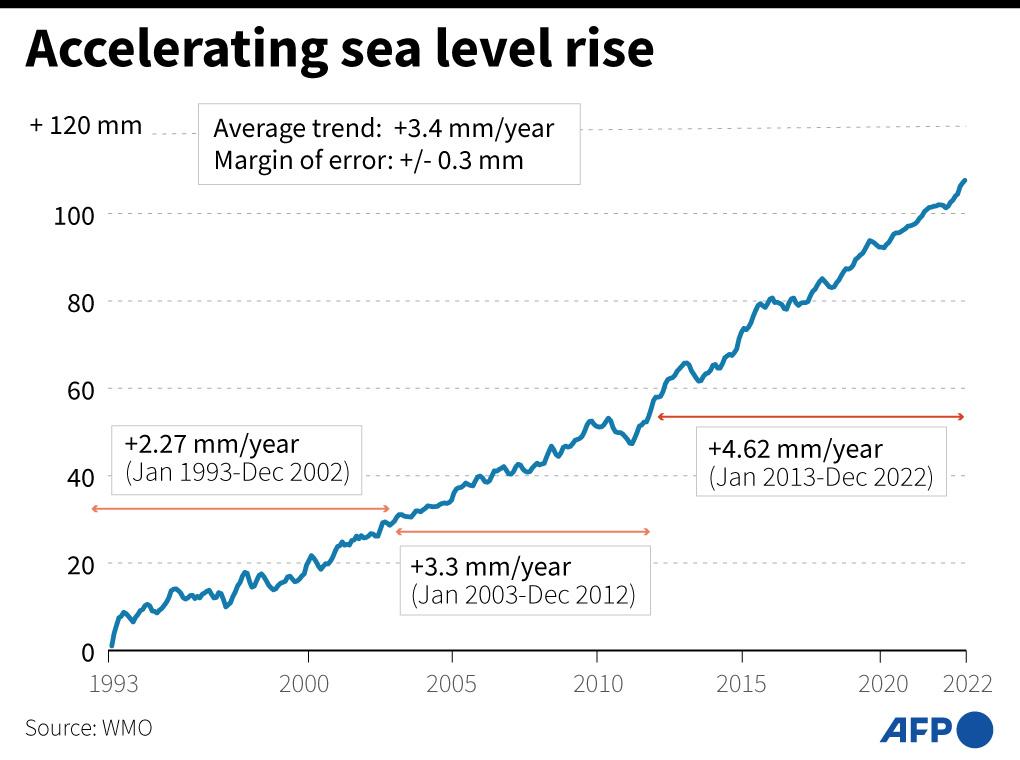

When people talk about the Maldives sinking, they are usually referring to relative sea-level rise. Relative sea-level rise combines the rise of the ocean with any vertical movement of the land. On the global side, the sea level is rising faster than in past decades. The World Meteorological Organization reports that the global mean sea-level rise rate increased from about 2.1 mm per year between 1993 and 2002 to around 4.7 mm per year between 2015 and 2024. NASA’s analysis of 2024 found an even higher annual rise of about 5.9 mm.

This matters for the Maldives because higher seas raise the baseline from which tides, waves and storm surges operate, increasing the frequency with which water reaches inland areas.

It is also important to understand that coral reef islands are dynamic. They can erode, grow or shift as sediments move. A 2023 study found that large shoreline changes observed in recent decades were not unprecedented over longer timescales, and that islands can change rather than shrink.

This does not eliminate risk. Instead, it shows that the Maldives sinking is not a single process, but a combination of rising seas and changing coastlines. There are several factors at play, not just rising sea levels.

The Maldives’ Sinking Rate

Looking specifically at the Maldives, sea-level rise around the islands averaged just under 4 mm per year between 1992 and 2015. Under high-emissions scenarios, the World Bank warns that annual rates later this century could increase to roughly 6-12 mm per year.

These numbers add up quickly. At 4 mm per year, sea levels can rise to about 4 cm over a decade, enough to significantly increase the frequency of coastal flooding and accelerate erosion on very low islands.

The Maldives’ Sinking Timeline – In How Many Years Will Maldives Sink?

There is no single deadline for when the Maldives will sink; the reality is more complex. There is no moment when the country suddenly disappears. Instead, there are thresholds. One is the permanent submergence of land. Another, often earlier, is uninhabitability, when flooding becomes frequent, fresh water becomes saline, infrastructure fails or protection costs become unmanageable.

The World Bank projects a sea-level rise of roughly 0.5-0.9 m by 2100 under high-warming scenarios. It also stresses that the sea level will continue rising beyond 2100, depending on future warming and ice-sheet responses.

Mid-century impacts are therefore critical. Human Rights Watch summarises scientific warnings that, without strong adaptation and emissions reductions, large parts of the Maldives could become uninhabitable by around 2050 due to flooding and freshwater stress. This framing helps explain why impacts are already being felt today.

Coastal Erosion and Climate Change in the Maldives

Rising sea levels amplify coastal flooding and erosion. The World Bank’s Country Climate and Development Report (CCDR) estimates that under projected sea-level rise, flood events with a 10-year return period could damage up to 3.3% of the country’s total assets. This will generate losses equivalent to hundreds of millions of dollars in GDP terms.

Tourism is particularly exposed. The World Bank reports that a large majority of surveyed resorts experienced moderate to severe beach erosion, and many reported infrastructure damage associated with climate-related events.

Sea-level rise also threatens freshwater supplies. Saltwater intrusion into shallow aquifers increases reliance on desalination, raising costs and energy demand. Coral reefs play a central role here as well. They reduce wave energy and supply sediments that help maintain islands over time. The annual flood protection provided by the country’s reefs is valued at about USD 442 million, roughly 8% of GDP. That protection is now under growing stress.

Can Maldives be saved? – Climate Adaptation

The Maldives is already investing heavily in adaptation, but more is needed. Adaptation solutions, including hard coastal defences, accommodation measures, nature-based solutions, land raising and reclamation and, in some cases, relocation are all viable options. For example, reclaimed islands such as Hulhumalé have been built at higher elevations to provide safer space for housing and infrastructure.

Global Warming Should be Addressed to Preserve Coral Reefs

Nature-based measures complement these efforts. Protecting reefs helps preserve their wave-buffering role, but only if warming and local pressures are addressed. NOAA confirmed the onset of a fourth global coral bleaching event in 2024, driven by widespread ocean heat stress. Without limiting global warming, adaptation becomes increasingly costly and less effective.

Adaptation Is Possible, but Only With Global Support

For the Maldives, staying abreast of climate change impacts is ultimately about whether low-lying island nations are given the time and resources to adapt to rising seas that they did little to cause. Alongside national adaptation efforts, the Maldives and other small island developing states have spent years pushing for stronger commitments on adaptation finance, loss and damage and faster emissions cuts at annual UN climate talks.

At COP27, countries agreed to establish a Loss and Damage Fund to support nations facing irreversible climate impacts, and by COP30, the fund was operational. However, funding levels remain far below what vulnerable countries need to respond to mounting climate impacts.

For the Maldives, access to predictable adaptation and loss and damage finance is critical to maintaining habitability, protecting fresh water and sustaining livelihoods in the face of future sea level rise. Without scaled-up global finance and faster mitigation, local adaptation can buy time, but it cannot fully offset the forces causing the Maldives to sink.

Eric Koons

Writer, United States

Eric is a passionate environmental advocate that believes renewable energy is a key piece in meeting the world’s growing energy demands. He received an environmental science degree from the University of California and has worked to promote environmentally and socially sustainable practices since. Eric has worked with leading environmental organisations, such as World Resources Institute and Hitachi ABB Power Grids.

Eric is a passionate environmental advocate that believes renewable energy is a key piece in meeting the world’s growing energy demands. He received an environmental science degree from the University of California and has worked to promote environmentally and socially sustainable practices since. Eric has worked with leading environmental organisations, such as World Resources Institute and Hitachi ABB Power Grids.