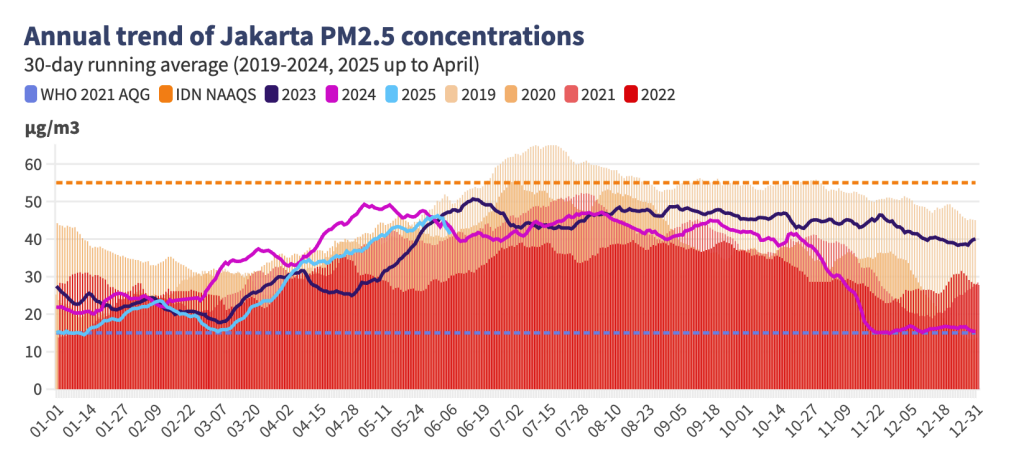

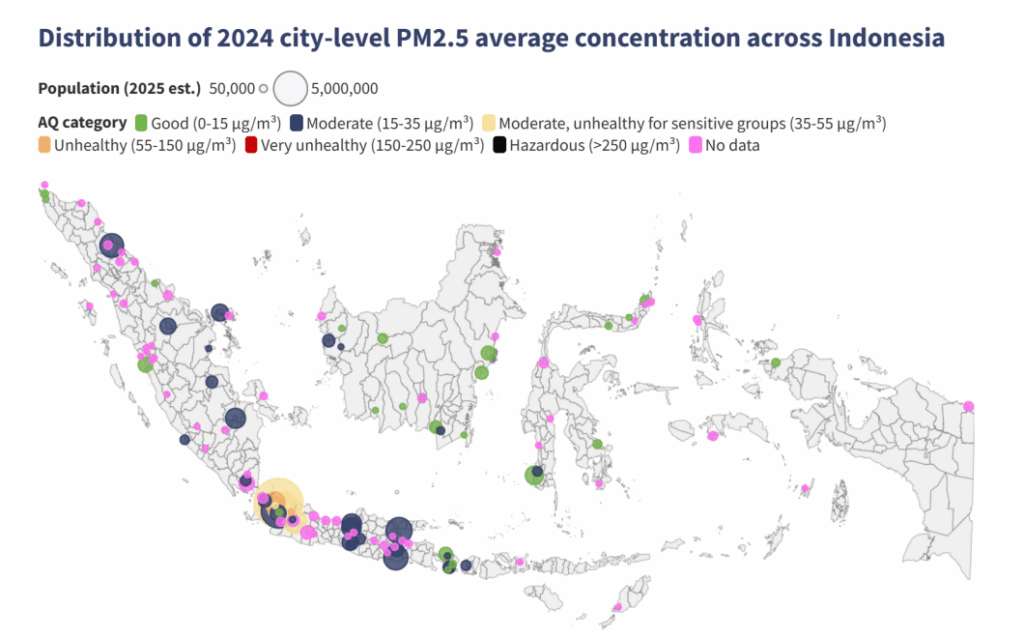

Air pollution in Indonesia isn’t a rare occurrence; it’s a yearly problem. In 2024, Indonesia’s population-weighted PM2.5 concentration averaged 35.5 µg/m³, ranking 15th in the world. At roughly seven times the WHO guideline of 5 µg/m³, it has significant impacts for the economy and social well-being of the world’s largest island nation.

Indonesia’s Air Pollution Snapshot: 2024-2025

Across the country, day-to-day conditions swing with weather, emissions and the dry season. IQAir’s 2024 ranking places Indonesia at the top of Southeast Asia’s pollution table and highlights city-level hotspots where PM2.5 routinely hits “unhealthy for sensitive groups”.

For readers tracking local alerts, Indonesia’s ISPU (Indeks Standar Pencemar Udara) translates pollutant measurements into risk categories to guide the public. The World Health Organization’s 2024 database provides a second reference point by compiling government-reported annual means for PM2.5, PM10 and NO₂. Together, they let us benchmark progress across provinces rather than relying on one dataset.

Where It’s Worst (And Why That Matters)

The most persistent air pollution exposure in Indonesia clusters around dense urban-industrial corridors on Java and in fire-prone provinces of Sumatra and Kalimantan. Jakarta regularly posts “moderate” to “unhealthy for sensitive groups” days. During peaks, western Indonesia’s cities can breach “unhealthy”. Sumatra and Kalimantan are heavily affected by peatland and forest fires during the dry season. Furthermore, these are getting worse due to extended droughts and global warming.

This matters because exposures compound: residents who commute along traffic corridors, live near busy roads or industrial areas and spend evenings in poorly ventilated spaces may see all-day exposure, not just the outdoor hourly spikes that dominate headlines.

The Monitoring Picture

One bright spot: monitoring is getting better. Jakarta now operates what the provincial government calls the most extensive, integrated air-quality monitoring system in Indonesia. It has 111 monitoring stations covering the city, which strengthens the evidence for targeted action. More and better monitoring is an essential long-term strategy, as it is the precondition for inventories, enforcement and public accountability.

What’s Driving Indonesia’s Air Pollution?

Indonesia’s mix in urban areas is familiar to rapidly growing economies. On-road transport (especially diesel fleets and motorcycles), coal-fired power and industry (SO₂, Nox), construction and road dust and waste burning are leading sources.

Specifically in Jakarta, a study identified vehicle emissions, open burning, construction soil and road dust, as well as coal, as leading contributors. Recent WRI Indonesia analysis reinforces this picture and links pollution peaks to El Niño–intensified dry spells.

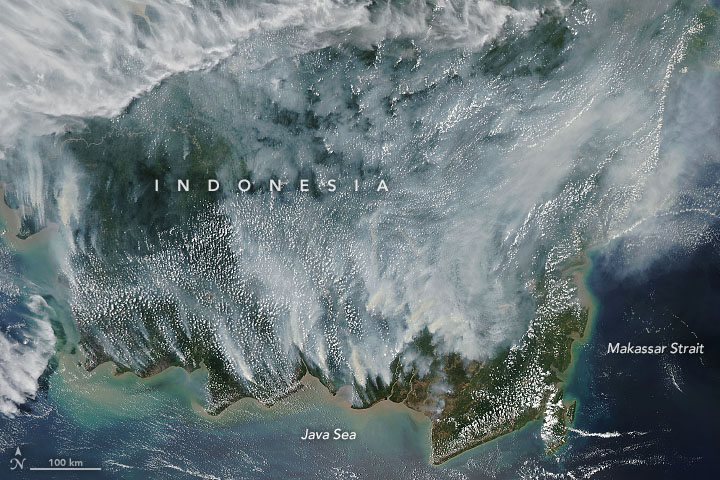

Seasonal Haze and Peat Fire Smoke

In the less urban areas of Kalimantan and Sumatra, forest fires are the dominant emissions source for much of the year. For example, in 2023 NASA documented the return of intense fires across Indonesia, amplified by El Niño. In mid-2025, ASEAN and media alerts again tracked hotspots across Sumatra and smoke crossing into Malaysia.

This is a continuous reminder that peatlands, once drained, become ignition-prone carbon sponges that burn for weeks and generate fine particles that travel. This creates not only a local issue, but also a regional concern that is challenging for neighbouring countries to handle.

Public Health Impacts and Economic Burden

The Health Effects Institute’s State of Global Air 2024 report finds air pollution accounted for 8.1 million deaths globally in 2021, now the world’s second-leading risk factor for death.

Indonesia is firmly in that global story. The Air Quality Life Index estimates today’s particle levels cut the average Indonesian’s life expectancy by about 1.3 years, with those in Jakarta losing over 2 years from life expectancy. From a macro lens, the World Bank pegs Indonesia’s annual health costs and economic losses from ambient air pollution at USD 220 billion. Jakarta alone accounts for USD 2.1 billion of that total.

Taken together, these human health losses and price-tagged damages make clean air action not just a public health imperative but also an economic one.

Policy Response: What’s in Motion And What to Watch

Indonesia has frameworks in place; the question is pace and follow-through.

In Jakarta, the 2019 Governor’s Instruction No. 66 laid out a multi-sector plan with vehicle emissions testing and renewal, public transport upgrades and enforcement against open burning. On mobility, Presidential Regulation No. 55 in 2019 kick-started the battery-electric vehicle (BEV) program and a 2023 amendment broadened the pathway for BEV deployment and localisation.

For fires, the central government’s peat-restoration agenda has been repeatedly affirmed. Independent analyses suggest peatland rewetting and restoration are among the most cost-effective ways to avoid haze-season spikes and their outsized health and fiscal impacts.

Climate Change Regulation

Complementing these direct air pollution measures is Indonesia’s climate policy. First, this is the country’s new nationally determined contribution (NDC) developed as part of the Paris Climate Agreement, which targets a conditional 43% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 2030. Along with this is Presidential Regulation 112 of 2022, which accelerates renewables and coal power plant retirements. Last is the 2023 Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP) investment and policy plan, which outlines a power sector roadmap to cut SO₂ and Nox emissions and retire coal facilities.

By shifting generation away from coal and tightening power sector emissions controls, these measures cut the precursors of fine particles and deliver immediate health co-benefits alongside emissions reductions.

From Data to Clean Air Outcomes

Indonesia has a clear path to measurable wins that reduce air pollution. Three outcome metrics tell the story: annual PM2.5 moving closer to the WHO guideline, fewer dry-season haze bulletins and hotspots flagged by the ASEAN Specialised Meteorological Centre and life expectancy losses narrowing in the next AQLI update.

The biggest levers map directly to those metrics. First, is enforcing transport emissions rules and accelerating fleet renewal to cut vehicular emissions. Next is addressing the industrial and power sectors by following the JETP roadmap. Last is limiting fire-related emissions by scaling peatland rewetting, which can avert billions in fire-related costs.

Framed this way, cleaner air becomes an annual objective with stepwise improvements leading to significant long-term changes.

Eric Koons

Writer, United States

Eric is a passionate environmental advocate that believes renewable energy is a key piece in meeting the world’s growing energy demands. He received an environmental science degree from the University of California and has worked to promote environmentally and socially sustainable practices since. Eric has worked with leading environmental organisations, such as World Resources Institute and Hitachi ABB Power Grids.

Eric is a passionate environmental advocate that believes renewable energy is a key piece in meeting the world’s growing energy demands. He received an environmental science degree from the University of California and has worked to promote environmentally and socially sustainable practices since. Eric has worked with leading environmental organisations, such as World Resources Institute and Hitachi ABB Power Grids.