After yet another year of shattered temperature records and relentless heatwaves, millions across Southeast Asia were cautiously optimistic that 2025 and the arrival of the cooling weather phenomenon La Niña, as forecast by the World Meteorological Organization, would bring some relief. However, nature once again showed that it can disprove even the most precise climate models, bringing an unusually weak La Niña. The cooling impact was short-lived, and Southeast Asia is again battling extreme heat. What’s worse, the heatwaves in Southeast Asia have arrived earlier. As authorities scramble to manage school closures, increasing energy demand and growing stress on the health system, the urgency to find solutions and protect the most vulnerable all across the region once again looms large.

The 2025 Heatwave Has Arrived Earlier to Torment All of South and Southeast Asia

Indonesia

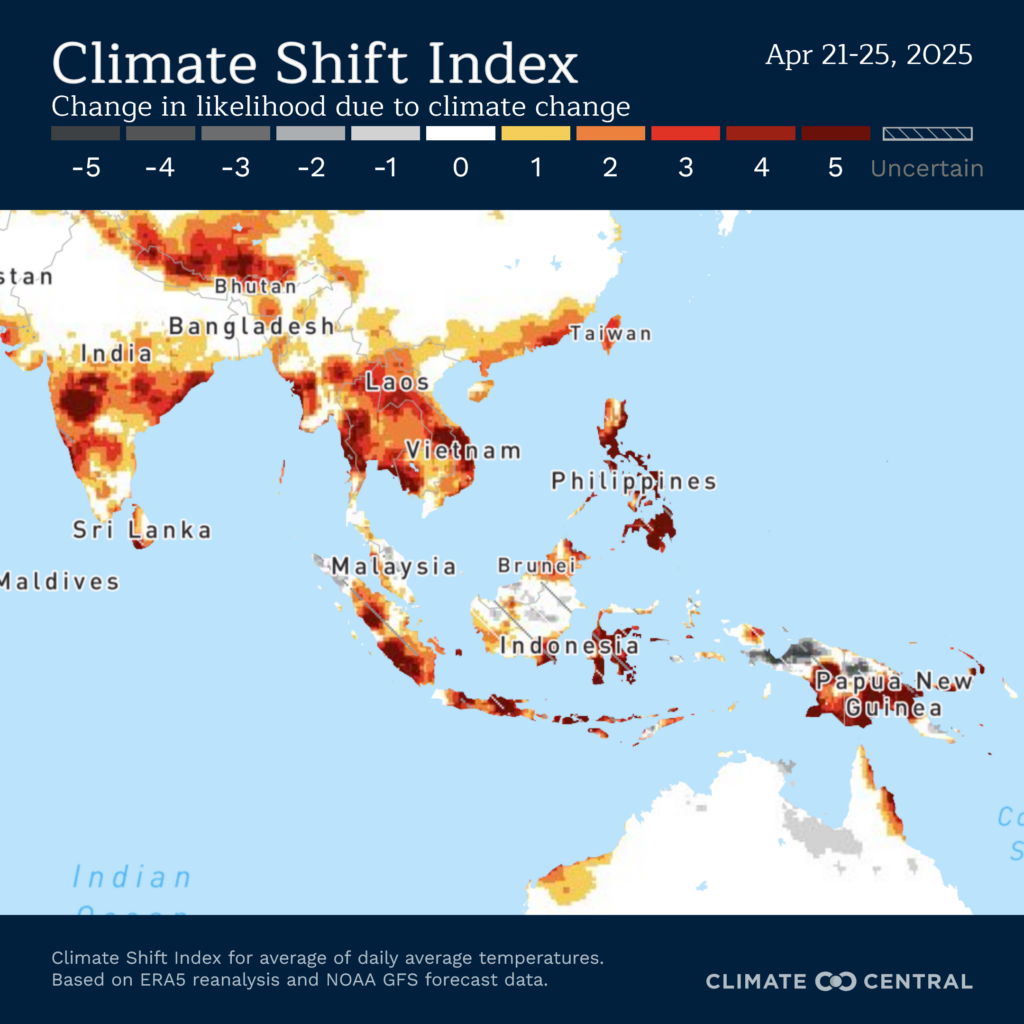

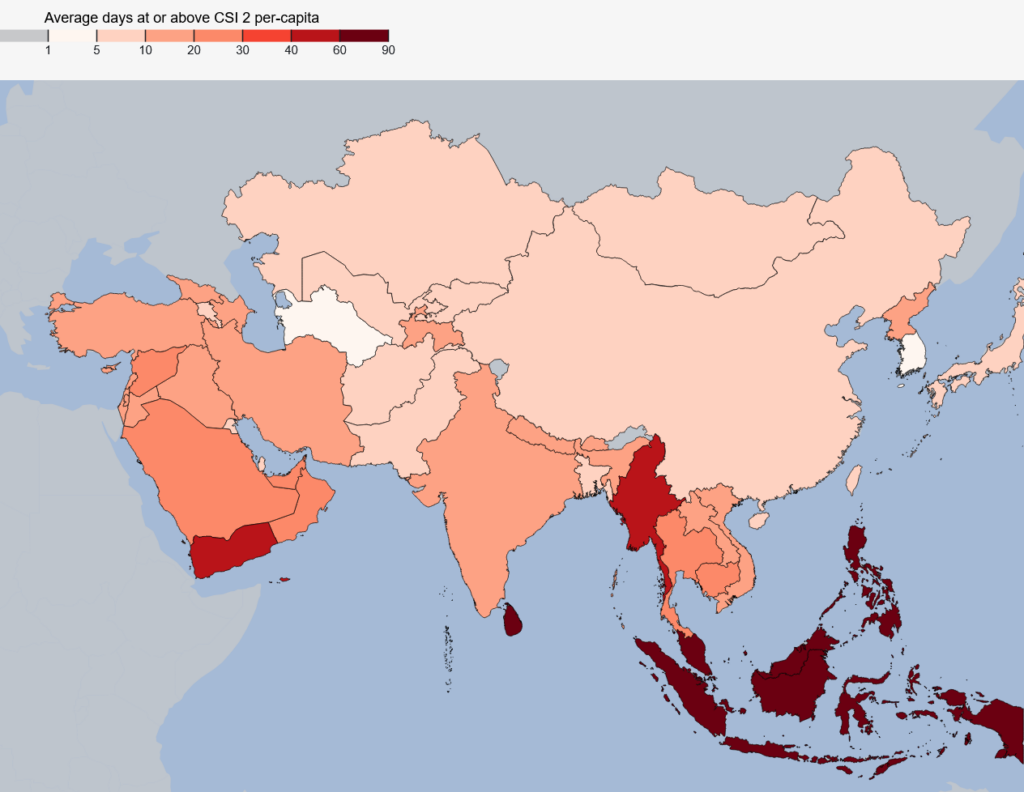

2025 brought extreme heat to Southeast Asia earlier. Jakarta, Indonesia and the Manila region in the Philippines experienced a period of extended and unusual heat between December 2024 and February 2025. According to scientists, climate change worsened the extremes on 70 days of the entire 90-day period.

Philippines

The severe heatwave disrupted Filipinos’ daily lives and key economic sectors like fisheries and agriculture. Throughout March and April, the Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration issued several warnings of a “dangerous” heat index, including temperatures between 42 and 51°C. In this category, there is increased risk of heat cramps, exhaustion and heatstroke. On some days, the extreme heat affected as many as 26 different areas of the country. In some regions, authorities had to shut schools down.

Myanmar

In Myanmar, the extreme heat complicated efforts to provide relief to the hundreds of thousands affected by the deadly 7.7 magnitude earthquake on March 28, killing over 3,600 people. Survivors, left without power, internet and sanitation, had to shelter in the open during the driest and hottest periods of the year. With temperatures soaring above 44°C throughout April, the hot season further compounds the humanitarian crisis. On some days, the scorching heat coincides with extreme downpours and destructive winds at night, increasing the risks of disease outbreaks, aid workers warn.

Thailand

Thailand wasn’t left unscathed, with temperatures hitting “very dangerous” levels in Phuket and “dangerous” levels in Bangkok and 34 other provinces at the end of April. According to the Meteorological Department, at these levels, people could feel that it was as hot as 52°C, even though the actual temperature was lower.

Vietnam

In Vietnam, the heatwave was less severe, with the mercury hitting 38°C in most northern and central provinces. According to the National Center for Hydro-Meteorological Forecasting, the country would be spared from severe heat extremes this year. Instead, authorities warn of mild heatwaves and severe rainfall between April and June. Still, the northern and central parts of the country are likely to experience prolonged high temperatures in July and August and a potential landfall of three storms forming over the East Sea between July and September. The authorities warn that while extreme heat may ease this year, the risks of heavy rains, storms and flooding remain high.

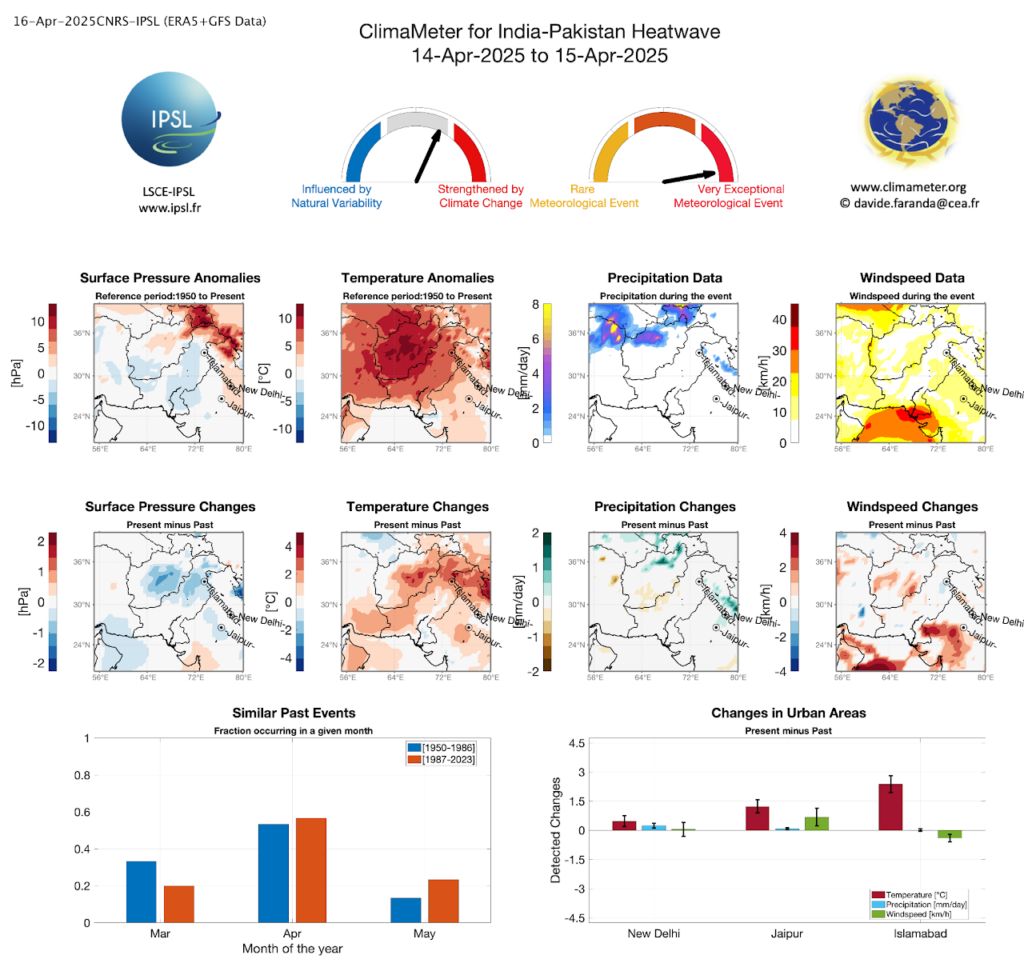

India and Pakistan

The heatwave that has been tormenting South Asian nations since February got worse, with temperatures in India and Pakistan reaching up to 8°C above seasonal norms in early April. This brought power outages, stress on the health system and triggered deadly thunderstorms. Some climate experts note that, by 2050, India will be among the first places where temperatures will cross survivability limits.

Looking Beyond Temperature: The Factors Exacerbating the Risk of Extreme Heat in Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia is accustomed to experiencing extreme summer heat. Scientists fear the situation will escalate as the trend of every consecutive year being hotter than the previous one, over the past decade, continues.

However, the progressively increasing temperatures are just one side of the problem. Another worrying trend is that early-season heatwaves are getting more frequent and dangerous. It is becoming increasingly common for scorching heat extremes to occur earlier, in spring, and last longer. Climate Central finds that six out of 11 cities that endured heat strongly influenced by climate change for 30 days or more between December 2024 and February 2025 were in Asia.

Due to human-induced climate change, the winters are getting shorter and the springs arrive earlier, which naturally extends the duration of periods of extreme temperatures. According to scientists, spring heatwaves are also significantly more dangerous than those traditionally occurring in summer, even at similar temperatures, since people don’t have enough time for acclimatisation after the winter months.

Scientists consider South Asia a window into the future of extreme heat. Recent studies revealed that events like the April 2025 heatwave were 4°C higher over the past 30 years than the average between 1950 and 1986. Disturbingly, academics found that the weather extremes took place during a neutral phase and not El Niño, which usually further boosts temperature rise.

Scientists warn that many cities across Iran, India, and Pakistan now regularly see wet bulb temperatures, threatening increased mortality rates, heat-related illnesses and food supply and agriculture disruptions.

According to experts cited by Vox, South Asia should brace for earlier, longer-lasting and hotter heatwaves going forward. But scientists warn that the same pattern examined in the region is also starting to affect countries like Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand and Vietnam.

The region’s high humidity also worsens the problem. For example, countries like Singapore, Indonesia, Thailand, the Philippines and Vietnam have average humidity levels of near or above 80% per year. In such conditions, even temperatures of 35°C pose a potentially fatal danger to humans outside due to the wet bulb effect. Such conditions make it harder for the body to cool down due to the inability of sweat to evaporate quickly from the skin.

Global Warming, Poverty, Demographic Factors and Rapid Urbanisation Risk Worsening the Deadly Impacts of Heatwaves

The WHO notes that population ageing is advancing rapidly across Southeast Asia. According to some studies, East Asia ages at the fastest rate in the world. Scientists have proven that most excess deaths during heatwaves occur in the elderly, whose bodies might struggle to withstand excessive heat.

Furthermore, Southeast Asia is experiencing rapid urbanisation, with over 200 million more people expected to relocate to cities by 2050. This transition could further complicate already existing problems in the region, like the lack of sufficient green spaces and the prevalence of heat-retaining surfaces such as concrete and asphalt, which strengthen the urban heat island effect. Aside from retaining heat throughout the day, it would also prevent proper cooling during nighttime, further increasing the heat stress on human bodies. Scientists note that this is a problem of particular concern for tropical East Asian cities, where high humidity compounds the risk of overheating. Another side effect of this trend would be ensuring adequate protection for outdoor workers, who are at higher risk of kidney, heart and other damage due to prolonged heat exposure and lack of proper hydration.

The World Bank estimates that today, 185 million people in the Asia-Pacific region live in extreme poverty, while over 260 million more could be pushed into poverty in the next decade, according to the UN’s ESCAP. The Asian Development Bank warns that poverty remains highest in South Asia. And scientists are clear: the poorest bear the biggest brunt of extreme heat.

Southeast Asia Isn’t Well Prepared to Handle Extreme Heat, But Solutions Exist

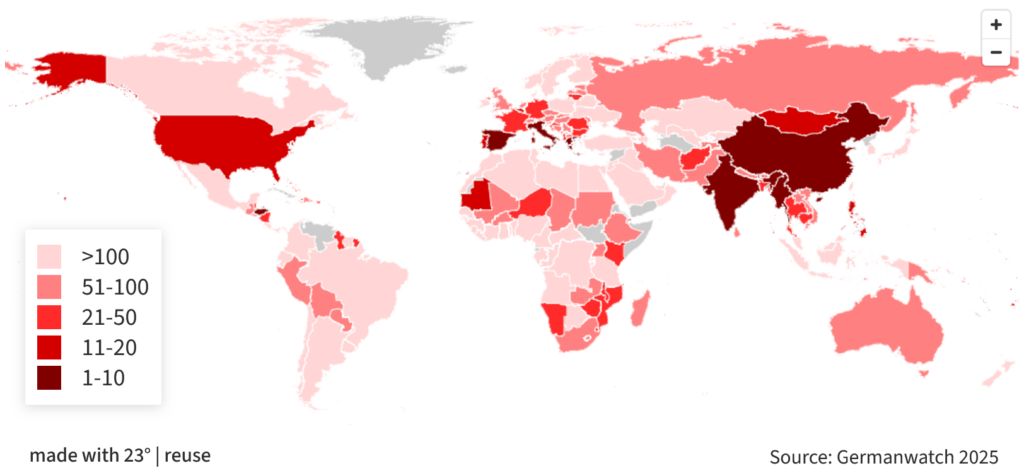

According to Germanwatch’s Global Climate Risk Index 2025, four of the top 10 most affected countries by climate change between 1993 and 2022 are from Asia. Myanmar (4th) incurred the highest number of fatalities, while China (2nd) and the Philippines (10th) had the most affected per 100,000.

The problem facing Southeast Asia is extremely complex and requires a combination of short- and long-term solutions.

In the short term, providing relief against extreme and prolonged heat requires expanding urban green spaces, establishing public cooling centres and prioritising easy and unrestricted water access for all. Retrofitting buildings, improving energy efficiency and addressing power supply shortages are also critical for ensuring adequate cooling throughout the hottest periods. It is imperative also to redesign urban planning and building codes to prioritise heat resilience. This would ensure natural cooling through better wind flow, improving ventilation across entire neighbourhoods or cities.

Developing heat action plans based on early warning systems, improved workplace regulations — like mandatory cooling breaks and access to ventilated areas — Indigenous knowledge and ongoing awareness campaigns are also crucial. While these efforts have only been partly successful in some countries, the scale of the problem calls for a well-coordinated regional approach. According to the Lowy Institute, an independent, nonpartisan international policy think tank located in Sydney, Australia, apart from a few domestic action plans, Asia-Pacific and ASEAN countries have failed to foster a regional response to the recurring crisis of excessive heat.

Governments in the region should also prioritise protecting the poorest parts of society by helping them escape poverty or cope with extreme heat.

In the long term, the leading solution to the problem — reducing carbon emissions to slow down temperature rise — isn’t solely in the hands of Southeast Asian nations. However, governments can also do their part by reconsidering their fossil fuel expansion plans, which remain some of the most ambitious worldwide.

While deploying and coordinating the necessary measures may seem complex, one thing is certain: the problem isn’t going away. In fact, scientific evidence warns that it’s likely to worsen, turning the need for action from a matter of preference into a matter of survival.

Viktor Tachev

Writer, Bulgaria

Viktor is a writer that specialises in green finance and ESG investment practices. He holds a Master's degree in financial markets and has over a decade of experience working with companies in the finance industry, along with international organisations and NGOs. Viktor is a regular contributor to several publications and comments on the likes of sustainability and renewable energy.

Viktor is a writer that specialises in green finance and ESG investment practices. He holds a Master's degree in financial markets and has over a decade of experience working with companies in the finance industry, along with international organisations and NGOs. Viktor is a regular contributor to several publications and comments on the likes of sustainability and renewable energy.